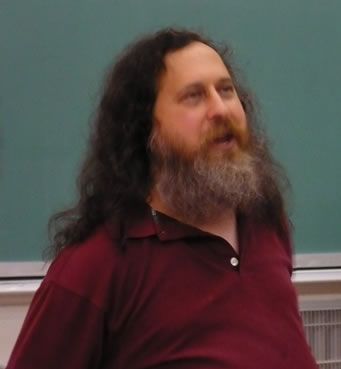

I attended last night’s presentation at the Mississauga Campus of the University of Toronto featuring Mr. Free Software himself, Richard M. Stallman. The presentation was titled Copyright vs. Community in the Age of Computer Networks.

Here’s a brief abstract of the presentation, courtesy of Greg Wilson’s blog:

Copyright developed in the age of the printing press, and was designed to fit with the system of centralized copying imposed by the printing press. But the copyright system does not fit well with computer networks, and only draconian punishments can enforce it.

The global corporations that profit from copyright are lobbying for draconian punishments, and to increase their copyright powers, while suppressing public access to technology. But if we seriously hope to serve the only legitimate purpose of copyright—to promote progress, for the benefit of the public—then we must make changes in the other direction.

Scott Graham, the new acting chair of Mathematical and Computing Science at U of T Mississauga did the introduction, after which I took notes, which appear below.

Note: anything in quotes is a direct quote from Stallman.

What’s This About?

- This is not a speech about free software

- Rather, it’s an answer to a question that people often asked me after my free software speeches

Free Software: A Quick Review

The Four Freedoms

- Free software is software that respects the user’s freedom

- Many people mistakenly believe it’s about software that’s free as in “no cost” because of the ambiguity of the English word “free”

- The “free” in “free software” is free as in the French libre, not as in the French gratuit

- The way we explain it to English speakers is “free as in speech, not free as in beer”

- We believe that there are 4 essential freedoms that a software user must have:

- Freedom 0: The freedom to run program as you wish, for any purpose.

- Freedom 1: The freedom to study the program’s source code to learn how it works and make changes to it. You need access to the source code to do this.

- Freedom 2: The freedom to help neighbour, by being able to distribute copies of the software.

- Freedom 3: The freedom to contribute to community by being able to give away your modified versions of the software.

The GNU Project and Linux

- The opposite of free software is proprietary software, which is unethical software

- The purpose of free software is to correct the social problem of proprietary software by replacing unethical proprietary software with an ethical system.

- In 1983, I set out to create a free operating system, GNU

- GNU is short for “GNU’s Not Unix”, a tip of the hat to the Unix operating system, from which GNU takes some technical ideas

- Began development of GNU in January 1984

- In 1992, GNU nearly had all the essential components to be a complete operating system

- The last gap was filled in 1992 by the Linux kernel, which was released in 1991, but adopted the GPL as its distribution licence in 1992

- The combination of GNU and Linux the Linux kernel formed a complete operating system, GNU plus Linux

- Many people call it “Linux”, which is wrong; Linux is just the kernel of the system, and ignores the effort that went into the other parts

- Through the 90s, more and more people invited me to talk about free software

- At the end of these talks, I would often be asked “Do these ideas apply to anything other than software?”

Applying Free Software Principles to Physical Objects

- For something to be free, it must respect the four freedoms

- Let’s test physical objects against the four freedoms:

- Freedom 0: Yes. If you own a physical obkject, you’re free to use it as you wish (within legal constraints). See? we’re already better off, rights-wise, with physical objects than with a lot of software.

- Freedom 1: Yes. In general, if you own a physical object, you’re free to make changes to it, as long as it was feasible.

- Freedom 2: No. It’s hard to copy an object. For physical objects, this is a meaningless question.

- Freedom 3: Once again meaningless, as it’s hard to make copies of physical objects

A Brief History of Copyright

- Information is different — it’s more easily copied

- With published works, copyright law is the only thing that might deny you the four freedoms

- Software isn’t like that, because a lot of it comes with additional restrictions

- What should copyright law say about those other kinds of works?

- We need to look at the history of copyright law

Ethics and Technology

- Copyright is closely connected to copying technology

- Technology can’t change basic ethical principles — they’re too deep

- However, we can apply basic ethical principles to new technologies

- Changes of context can change the consequences — consider: if we ever developed a technology that could realibly resurrect the dead, would murder still be a serious crime?

Copying By Hand

- In the ancient world, copying was simple: you read one copy, you wrote another

- Using this method of copying, there are no economies of scale — to make 10 copies took 10 times as long

- No special skill or equipment was needed, other than the skill and tools to read and write (which in those days, few people had)

- Result: copying was done in a decentralized fashion

- As far as I can tell, nothing like copyright in the ancient world

The Printing Press

- The printing press represented an advance in copying

- It made copying more efficient, but not uniformly — some kinds of copying worked better than others

- Printing was relatively fast, but setting up the type was time-consuming

- Efficient only for mass production

- It required specialized equipment and skill, which most people didn’t have it

- Result: copying was done in a centralized fashion

- Hand-copying still common in the first centuries of printing: they very rich had hand-copied books because custom books were expensive, as did the very poor, because copying books was the only way they could own one

Precursors to Copyright

- The concept of copyright began in the age of the printing press, c. 1500

- The first English system that was similar to copyright was a form of censorship — a permanent monopoly granted by the king to a publisher

- This was — “after the glorious revolution” — replaced with a system of copyright, which was granted to the author for 14 years

- Copyright was meant to encourage writing by making it more feasible for authors to make money from writing

- It was a constitutional decision: Congress was allowed to set up a copyright system as a means of promoting progress

- Not an entitlement, but an artifical scheme to modify people’s behaviour, to encourage the production of works to better society

- It was also a constitutional decision that copyright must last for a limited time

Copyright as Originally Intended

- The media corporations want people to believe copyright is something that authors inherently have and then hand over to publishers; they don’t want people to think of it in its intended context

- It’s an industrial regulation: copyright is meant to restrict what publishers could do, not readers

- As an industrial regulation, it was:

- Fairly painless: readers were not restricted

- Easy to enforce: it was enforced only against publishers, and it wasn’t necessary to invade people’s homes to enforce it

- Publicly beneficial: people traded away a freedom they couldn’t exercise anyway, and they got a benefit

- As a result, copyright wasn’t very controversial

Copyright Now

- Now with digital data and computer networks, it much easier for us to copy and manipulate information

- Digital technology has changed the effect of copyright law

- Copyright used to be a power that was:

- wielded by authors

- over publishers

- to yield benefits to the public

- Now it’s a power that is:

- wielded by publishers

- to punish the public

- in the name of the authors

- Now the public wants to copy and share — what would a democratic government do?

- They’d say “We have to renegotiate this deal, now that the freedom freedom to copy can be exercised”

- You can measure the non-democratic tendencies of a government by their tendencies to do the opposite of the previous statement

Copyright’s Expanding Time

- Consider the dimension of time

- In 1998, the copyright period was extended by 20 years for both old and new works

- Extending copyright for old works: Did they have a time machine? How did they hope to encourage authors in the 1920’s to make new stuff?

- Extending copyright for new works: 20 more years of copyright now might theoretically encourage the creation of more works, but the marginal value of 20 more years of copyright discounted for 75 years in the future is zero

- Can a publisher give their projected balance sheets for 75 years in the future? Most industries don’t plan beyond the next 5 years

- Clearly, it’s just an excuse — politicians have been bought with campaign contributions and the corporate media are not examining it

- The law is the “Sonny Bono Copyright Act” — he was the Church of Scientology’s pet congressman, and they use copyright law to silence critics

- The law is also known as the Mickey Mouse copyright act since it was paid for by Disney

- The copyright of the first Mickey Mouse cartoons, Steamboat Willie, was about to expire [ed. note. Steamboat Willie is not the first cartoon to feature Mickey Mouse, but it’s the one that made Mickey famous.]

- Steamboat Willie itself borrowed from other films

- This is “perpetual copyright on the installment plan”: they can’t officially establish copyright forever, so they do the next best thing: extend it for 20 years every 20 years

- The idea: nothing should ever go into the public domain again

- When there is a problem in the U.S., it doesn’t try to solve that problem, it tries to impose it worldwide — as with copyright

Copyright’s Expanding Breadth

- Now consider the dimension of breadth

- Copyright was not meant to restrict all uses of a work, just some

- In 1998, publishers got the DMCA passed, giving them total power

- It allows them to implement whatever rules they want, and bypassing them is illegal

- It effectively allows publishers to write their own laws

- DVDs: You have the right to watch them, but only on authorized players

- You do not have the right to use a free player

- The only authorized players are designed to restrict you — see defectivebydesign.org

- In France, it’s illegal to even possess a copy of the free software that can play DVDs

- In music, there are these “corrupt discs that look like real compact discs”, which are unreadable by computers

- In some countries, they have to be labelled as such

- Once while in Spain, I was given such a disc and I said: “Here we see the face of the enemy. Please take this back to the store because I don’t want them to keep your money.”

- Since there is free software that can read encrypted DVDs, movie compnies want a replacement system and came up with AACS (used in HD-DVD and Blu-Ray)

- “Give AACS the axe!”

- It didn’t take long for ACCS to be cracked — someone found the key and published it

- It was posted on many community sites, and although those sites took those posts down, other people re-posted

- It was “an upswell of popular resistance against a new tyranny”

- “Just seeing that the spirit of resistance can well up doesn’t mean it’s over”

- Consider the Sony rootkit [a.k.a. XCP — Extended Copy Protection]

- It contained illegally copied GNU software (it did not follow the terms of the GPL in copying it)

- In spite of this, Sony wasn’t prosecuted for copyright infringement (only ordinary people will get charged with that!)

- Sony was made to promise never again include a rootkit in their materials

- So they’re doing an end run by putting rootkits right into computers from the get-go

- And this rootkit? “It’s called Windows Vista”

- “Restricting users is the purpose of Windows Vista”

- Visit BadVista.org for details

- “Even if you’re not ready to escape to the free world, at least don’t let Microsoft tighten the chains on you!”

- “Vista is one big back door”

- It forces users to use specific software>/li>

- It enabled Microsoft to send a command to computers running Vista to stop using any specified piece of hardware (useful if the hardware doesn’t support DRM or other similar anti-user measures)

- “What arrogance!”

eBooks

- Book publishers would like to take away certain traditional freedoms associated with books, such as:

- The freedom to read it anywhere you like

- The freedom to borrow it from a library

- The freedom to lend it to a friend

- The freedom to sell it at a used bookstore

- The freedom to keep the book as long as you want and pass it on to your kids

- Publishers realize that they might face opposition to the loss of these freedoms, so they’re trying to sneak it in through ebooks

- The DMCA took away these freedoms from ebooks — now the next step was to get people to switch to ebooks

- The first step worked, but the second didn’t, but not because people valued their freedom too much; rather it’s that reading off the screen wasn’t good enough

- The screen-reading experience will improve with epaper, and then the publishers will try again

- There’s a dental school in the U.S. where all the textbooks are ebooks that expire after a year

- I had a brush with ebooks: a publisher that wanted to start a line of ebooks with my biography

- I would only let them do this if they would publish it unencrypted. They balked, but eventually, there was a publisher who would agree to my terms

- There’s an organized hype campaign to promote ebooks

- One bit of evidence: on a flight in Brazil, I was reading an in-flight magazine and in the spot where there would be an editoral in a “real” magazine, there was an article speculating on how many years it would take for ebooks to be adopted

- In airline magazine, unless the article is about a destination that the airline covers, you can be sure it’s paid for

- We can be sure that they’ll push ebooks again

- We have to be constantly ready to defend our freedom

- What would governments do if they were truly democratic?

- They’d reduce the amount of power exercised over us

Proposed Changes to Copyright Time

- Let’s look again at the dimension of time

- Instead of extending copyright terms, reduce them!

- Over time, we’ve seen that the publication cycle has been getting shorter

- In U.S., and I’m sure the situation is similar in Canada, most books are remaindered within 2 years and out of print within 3

- Shorten the copyright period to a decade, starting with date of publication (rather than the date it’s finished being created; we want authors to have the time to find a publisher) — start the clock ticking at the time of first publication

- When I proposed this, a well-known fantasy author beside me said “10 years? Anything more than 5 is intolerable!”

- Copyright not good for most authors. Superstars, yes, but for most authors, no

- Publishers grind authors at the same time they “defend” them

- The fantasy author beside me told me that he wanted the rights to his book back since they were out of print, nut his publisher kept claiming they weren’t (meaning that the rights still rested with them)

- He had to sue to get his rights back — that is, to get permission to hand out copies of his own books

- This sort of thing is not unusual; it extends to all fields

- More than 5 years of copyright would not affect him unless he became a superstar

- We should start with a 10-year copyright period, watch the results, and fine-tune the length of the period as needed

- This will get rid of the bulk of the problems we have now where copyright can sometimes last 150 years

Proposed Changes to Copyright Breadth

- Now let’s look at the dimension of breadth

- We should arramge different copyright deals for different kinds of works

- Works should be distinguished not by media, but by the way the works contribute to society

- Each type of work is important in a different way, but no type is more important than any other

- Works could be divided into these three categories:

- Practical functional works

- Works that witness the thoughts of certain parties

- Arts and entertainment

Practical functional works

- These are things that we use to do practical useful work

- Examples:

- Reference works

- Educational material

- Designs of equipment and buildings

- Programs

- Recipes

- Fonts

- These must be free (as in the four freedoms). If you use the work to do practical things, you must be free to control what you do.

- These are things that society needs

- There must be freedom to distribute unmodified and modified versions of these works

- 20 years ago, it might have been rational to say that without a scheme to restrict the sharing of such works

- Proprietary software makes no contribution to society

- I would like to maximize the amount of free software and minimize the amount of proprietary software, “preferably to zero”

- Society’s needs can be satisfied by free software

- Look at recipes: recipes are shared, yet there are gainfully-employed cooks everywhere

- Look at Wikipedia: it’s proof that it’s possible for a free reference work to exist and also be good

- Educational works need to be free

Works that witness the thoughts of certain parties

- Modifying these works misrepresents the authors

- When I write essays, I don’t grant the permission to modify them

- I recommend a compromise copyright system that would prohibit modification and commercial distribution

- There would still be the freedom to non-commercially distribute unmodfied copies

- Sharing the basis of society — attacking sharing attacks the basis of society — “That’s as anti-social as anything gets”

- The same as now, but with an essential minimum freedom

Arts and entertainment

- The purpose of these works lies in the impact they make on the user

- The issue of whether to allow modification: difficult to deal with

- There are valid arguments on both sides

- One on hand:

- A work can have an artistic integrity

- This is sometimes true…

- But not as often as the authors think!

- Witness the number of authors who are all too willing to have Hollywood butcher their work

- On the other hand:

- Modification is a way to make a contribution to art

- The folk process is based on modifying work

- Consider Shakespeare: he borrowed plots from other plays written just decades before — they’d be illegal if done today — one could say to him “You’re just making a cheap ripoff”

- In the end, what allowed me to resolve this is that there’s no rush to make a modfied version of a work

- “You can wait 10 years!”

- This restriction is not acceptable for works of practical use, but acceptable for works of art

- I propose a compromise: you should be free to non-commerically distribute unmodified copies for 10 years, after which you should be free to distribute modified copies

On Music Sharing

- Music sharing on the net should be legal

- Record companies like to pretend it’s a disaster for musicians

- But really, musicians can’t lose what they’re not getting

- Mainly long-established superstars are the only ones making money from their records

- The rest generally don’t unless they’re wildly successful

- Overall, the record companies make up for 4% of all musicians’ income

- The money given to a band to cover the costs of publicity and recording is considered to be an “advance”

- Given that the record companies treat the musicans so badly, musicians aren’t going to lose money if we don’t buy their records

- The main benefit of the record companies to musicians is that they provide publicity, which in turn gets people to attend their concerts, which is where they really make their money

- We can give them publicity by sharing their music

- “Pry loose of the grip of the hype”

- The record companies just provide “carloads of money, squeeze it into something like music and dish it out at us”

- Music will be better off without them

- Legalize music sharing

- Also: support musicians better

- There are two ways we can do this:

- 1. A tax:

- A tax on anything that relates to internet use

- Divide up this money among musicians based on their popularity, but not in linear fashion

- Have function that tapers off

- A superstar that is 1000 times as popular will not get 1000 times the money, but 10 times

- Guarantees better money across the board for all musicians

- Want the tax to support musicians so they don’t have to get a day job, but concentrate on their music

- 2. Voluntary payments:

- Imagine if every player had a button you could push to send a dollar to the band

- “You wouldn’t miss one dollar”

- Imagine people pushing that button once a month or even once a week

- Read: I read that the average American spent $20/year on music

- If the average American sent a dollar a year directly to the musicans, musicians would be supported just as well as the current system

- If they push the button twice a year, that would cover not just performers, but composers too

- We could make a PR capaign with a positive message, instead of those “piracy” campaigns: “You like those bands, have you sent them a dollar today?”

- I don’t like the way they equate people who share music and movies they like with people who rob ships at sea

- 1. A tax:

Q & A Session

“How can programmers hope to make money under free software?”

One of the first questions was the inevitable one about how programmers can make money with free software. I skipped taking notes for this one, as I needed a break from typing and I’ve seen this played out time and again. The guy who asked the question — presumably a student — made the mistake of referring to the operating system as “Linux” and not “GNU plus Linux” or “GNU/Linux” when talking to Stallman, which prompted the usual eruption.

I could’ve sworn that knowing never to call it just plain “Linux” in front of RMS was basic knowledge or lore in our field, but perhaps I’m just not seeing it from a student’s perspective.

Question about the GPL

RMS pointed out that any license that recognizes the four freedoms is free software. When asked about what the GPL v3 had to say about “software as a service”, RMS asked the person to clarify what he meant by that term (he hates terminology he considers ambiguous).

The person asked if a service that lives on a server was being used, did the users have the four freedoms with the software behind that service?

His answer was that the four freedoms in that case belonged to the owner of that server. He also said that if you run a service and the software is under the GNU Afero licence, you have to share the code. The GNU GPL3 licence does not require this.

Question about patents

When asked about patents, Stallman said:

- There is nothing in common between copyright law and patent law — this is a widespread misconception

- The issues they raise have nothing in common

- Comes from the fashionable and misleading term intellectual property”

- The term is used to confuse

- Reject the term “intellectual property”

- I’m not totally against either law, but applying patent law to software creates a problem

- Developing a program require incorporating a large number of ideas

- Software patents are “an absurd system of getting software developers tied up in knots”

- Corporations file patents because they figure they’ll gain on the balance

- Software patents should not exist

- An analogy: software and say, symphonic music or novels:

- They combine lots of ideas

- Suppose each idea could be patented — what would the effect be?

- There is no danger that someone you’ve never heard of or never dealt with will have copyright on your work

- But there is a danger that someone you’ve never heard of or never dealt with might have a patent on something in your work

- In the U.S. Constitution, copyrights and patents each have one line

- Amother ambiguity with the term “intellectual property” is that it includes tradmark law, which unlike copyrights and patents, is not an incentive for creators

- The term “intellectual property” generalizes too far

- Whenever you hear someone say it, say “Hold on, this discussion is confused! IP is not a coherent reference to anything!”

One Final Word

He closed with “Get active and fight against [Canadian copyright bill] C-60…and I don’t mean Buckyballs!”

14 replies on “Richard M. Stallman: Copyright vs. Community in the Age of Computer Networks”

Holy cow, this is really thorough. Thanks for doing this, Joey. I feel like I was

therea fly on the wall.On an utterly, thoroughly different topic altogether, can you say why you’re not on the blogware platform anymore (or are you)?

So did RMS answer the question of how programmers make money writing free software?

Thanks, these are very readable yet detailed notes!

Actually until today I agreed with equating illegal file sharing with piracy – but now I’m thinking I have to rethink my concepts…

Joey,

A great post and I thank you for it. This is a serious issue – especially from the educational side of things.

I’m an educator and run a site for English teachers (as a second/foreign language). Only probably someone like yourself can know the hassle, the stress, the frustration I’ve experienced trying to give educators access to valuable educational materials so they can give students knowledge and skills.

I keep at it – the times are a changing (if rather slowly). Thanks,

David

Great blog, clear thinking, I’ll pass it along… thank you!

[…] in the Age of Computer Networks”. I’d write a synopsis, but Joey DeVilla has a virtual play-by-play on his blog of another time Stallman gave the speech. This is another topic that I could probably write a lot […]

Great Joey!

I didn’t really take any note during CUSEC 09 and felt a bit bad about it cause I didn’t remember it all. Didn’t read it all, but it looks similar to the presentation we had.

Thanks

[…] up any of the figures that he prefixes with “and I think that..” You may as well just read Joey deVilla’s notes. While you’re at it, read how as a Microsoft evangelist he subsidized the Free Software […]

[…] 13.-án kb 500-600 néző előtt tartott egy előadást “Copyright vs. Community in the Age of Computer Networks” címen, mindezt az Open Source Farm szervezőinek köszönhetően. Az előadás után rms szerepelt […]

[…] presented a bold plan for the future of copyright. (Joey deVilla at Global Nerdy has posted a detailed outline of a lecture by the same title that Stallman gave at the University of Toronto in July.) In short, […]

I videotaped Stallman giving the same talk at Cardozo Law School in NYC on Mar 31 2009.

Audio/video is at http://punkcast.com/1552/.

[…] http://www.globalnerdy.com/2007/07/06/richard-m-stallman-copyright-vs-community-in-the-age-of-comput… […]

[…] Richard M. Stallman: Copyright vs. Community in the Age of Computer Networks – Mr. Free Software himself, Richard M. Stallman, gave a presentation at the Mississauga Campus of the University of Toronto. AG has notes from the speak. […]

[…] The CUSEC convention’s last keynote speech was Richard Stallman’s presentation titled Copyright vs. Community in the Age of Computer Networks. It’s similar to the one he gave at the University of Toronto in the summer of 2007; you can see my detailed notes on that presentation here. […]