With smartphone ownership in the US hitting nearly 60% at the start of this year, and data usage among those smartphone users climbing, it’s only expected that the war between wireless carriers is heating up. In this installment of our regular look at the wireless carrier industry, we provide an introduction to the two major fronts what they’re fighting over: customers and spectrum.

The fight for customers

The rise of the smartphone raised the stakes for wireless carriers, and as more people use them more often, and as more devices become wireless network-enabled, the carriers’ battle for your business has become more intense. In the open, the war’s about customers, as you’ve likely seen through the recent carrier advertising campaigns and promotions, many of which have been driven by T-Mobile’s recent “Uncarrier” approach. If you look at Pew Internet’s latest figure on wireless-enabled device ownership in the US (they update them regularly; the ones we’re citing are from January 2014), you can see why the fight’s becoming more intense:

- 90% of American adults have a cell phone

- 58% of American adults have a smartphone

- 32% of American adults own an e-reader

- 42% of American adults own a tablet computer

Click the graph to see the source.

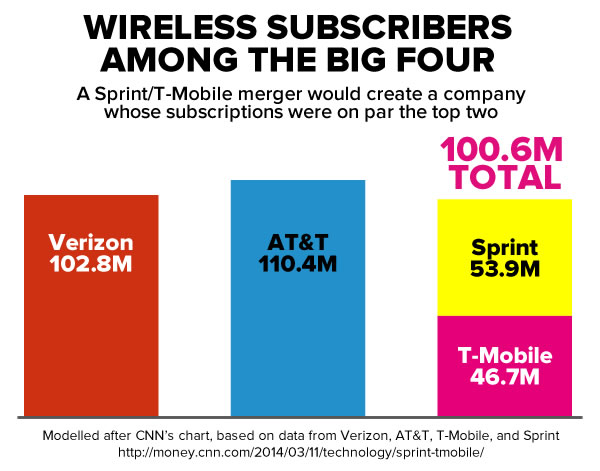

Currently, AT&T and Verizon are the two giants of the US wireless carriers, each about the same size, with AT&T at 110 million subscriptions and Verizon at 103 million. The next two, Sprint and T-Mobile, are about half the giants’ sizes, with 54 million and 47 million subscribers, respectively. Masayoshi Son, CEO of the Japanese telco Softbank and Chairman of Sprint, has announced that he’d love for Sprint to purchase T-Mobile, thereby creating a carrier whose subscriber base would be on the same order of magnitude as the Big Two. “With scale merit,” said Son in a recent Sprint earnings call, “we don’t have to settle with No. 3. We can compete fiercely.” It’s an audacious plan, but most pundits say that it’s not likely to get approved by US regulators.

The fight for spectrum

Behind the scenes, the carriers are fighting for something else: spectrum — a range of radio frequencies assigned for use by wireless carriers for the transmission of voice and data. Each radio frequency in these bands is capable of carrying a certain amount of data at any given moment, and as more wireless users go online, the frequency becomes more crowded. This means that more users make use of a given frequency, it has to be divided among more people, giving each user a smaller “slice”, slowing data transmissions.

Luckily for the carriers, a block of frequencies will soon become available. The frequencies, which are in the range of 600 megahertz, are currently used by television stations, and the FCC is “voluntelling” the stations to yield them, and if they don’t, may move them to other frequencies. These frequencies are so desirable that the industry nickname for them is “beachfront property” because of their properties: they travel farther than radio waves in the frequencies currently used in the US (850 megahertz and 1900 megahertz), pass through buildings, hills, and vegetation better, and require fewer towers. Simply put, the 600 megahertz band offers better range, less dropped connections and is cheaper to operate.

This band of frequencies will soon be made available via auction to eligible parties. As of August 2012, AT&T and Verizon own about three-quarters of the lower-band frequencies, with Sprint owning 12%, and T-Mobile owning less than a percent. Sprint and T-Mobile’s radio spectrum is largely in higher-freqnecy bands, which can carry more data, and serve them well in population- and tower-dense city areas. However, corporate accountants view the lower frequencies as more valuable assets; in fact, Verizon’s accounts have their frequencies in their books as worth more than all their properties and equipment combined.

There’s considerable evidence that the auction, as currently set up, favors AT&T and Verizon, much to the chagrin of T-Mobile and Sprint. The stakes are high enough that the carriers have been spending considerable sums not just on lobbying, but influence. American University professor James Thurber, who’s been studying lobbying for three decades, says that the carriers have likely spent as much as $80 million — twice their lobbying spending — on behind-the-scenes promotions in which they give cash to PR firms, think tanks, “grassroots” and “toproots” organizations, academics, and other influencers, all in order to shift perceptions in their favour. This less-seen battle is covered in a recent Slate article that says that the future of wireless communication may be decided by a massive influence web of lobbyists, think tanks, and academics who are paid for their opinions.