I’ve been at a number of holiday parties over the past week, and at every one, I’ve been asked about how ChatGPT works. All the explaining stirred up an old memory from a book I read back in high school: The Spy’s Bedside Book, an anthology of spy and espionage stories edited by Graham Greene and his younger brother Hugh Greene, and in particular, an O. Henry story titled Calloway’s Code.

The technology behind ChatGPT and other similar software is a Large Language Model, or LLM for short. The general idea behind it to try to predict the next word or sequence of words in a given text based on prior words.

For instance, if you’re a native English speaker or have been living in the Anglosphere for some time, you can probably predict the word that goes in the blank below:

To be, or not to be, that is the ________:

In Calloway’s Code, the titular character — a field journalist named Calloway — uses this predictive approach as a means of encryption.

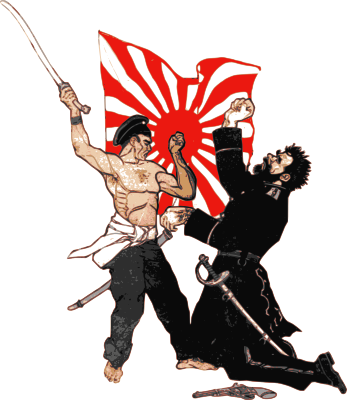

The story is set during the Russo-Japanese War, which took place from 1904 to 1905, where Russia and Japan were fighting for control over Manchuria and Korea. Calloway was reporting from the front lines of the war for a newspaper named the New York Enterprise.

It being the very early 1900s, Calloway had to write his reports (by hand, no less!) and give it to a cablegram operator to send, which meant that all his work had to be approved by a local censor. So he sent this message:

Foregone preconcerted rash witching goes muffled rumour mine dark silent unfortunate richmond existing great hotly brute select mooted parlous beggars ye angel incontrovertible.

As the story puts it, someone who wasn’t a native English speaker would think it “meant no more than a complaint of the dearth of news and a petition for more expense money.”

The journalists at the Enterprise bullpen knew it had to be some kind of encoded message:

“It’s undoubtedly a code. It’s impossible to read it without the key. Has the office ever used a cipher code?”

“Just what I was asking,” said the m.e. [managing editor] “Hustle everybody up that ought to know. We must get at it some way. Calloway has evidently got hold of some- thing big, and the censor has put the screws on, or he wouldn’t have cabled in a lot of chop suey like this.”

Everyone was stumped until the youngest reporter, Vesey, stepped into the office. The others presented him with the cablegram, and shortly after staring at it, Vesey said “I believe I’ve got a line on it. Give me ten minutes.”

Fifteen minutes later, he returned with this translation table:

- Foregone — conclusion

- Preconcerted — arrangement

- Rash — act

- Witching — hour of midnight

- Goes — without saying

- Muffled — report

- Rumour — hath it

- Mine — host

- Dark — horse

- Silent — majority

- Unfortunate — pedestrians

- Richmond — in the field

- Existing — conditions

- Great — White Way

- Hotly — contested

- Brute — force

- Select — few

- Mooted — question

- Parlous — times

- Beggars — description

- Ye — correspondent

- Angel — unawares

- Incontrovertible — fact

He explained his reasoning:

“It’s simply newspaper English,” explained Vesey. “I’ve been reporting on the Enterprise long enough to know it by heart. Old Calloway gives us the cue word, and we use the word that naturally follows it just as we em in the paper. Read it over, and you’ll see how pat they drop into their places. Now, here’s the message he intended us to get.”

Using Vesey’s translation table, Calloway’s message became:

Concluded arrangement to act at hour of midnight without saying. Report hath it that a large body of cavalry and an overwhelming force of infantry will be thrown into the field. Conditions white. Way contested by only a small force. Question the Times description. Its correspondent is unaware of the facts.

The deciphering wasn’t perfect, but it was good enough. Here’s where the error crept in:

Only one error was made; and that was the fault of the cable operator at Wi-ju. Calloway pointed it out after he came back. The word “great” in his code should have been “gage,” and its complemental words “of battle.” But it went to Ames “conditions white,” and of course [a writer at the Enterprise] took that to mean snow. His description of the Japanese army strum, struggling through the snowstorm, blinded by the whirling, flakes, was thrillingly vivid. The artists turned out some effective illustrations that made a hit as pictures of the artillery dragging their guns through the drifts. But, as the attack was made on the first day of May, “conditions white” excited some amusement. But it in made no difference to the Enterprise, anyway.

📖 You can read Calloway’s Code online here.

Bonus video!

Here’s a video from The Black Chamber, a YouTube channel dedicated to recreational cryptography, that looks at Calloway’s code. If you’d like to get into cryptography, check out the rest of their channel!

2 replies on “The basis for ChatGPT appears in an old O. Henry short story”

You beat me to it! My copy of Calloway’s Code was in Famous Stories of Code and Cipher (Raymond T. Bond, ed.). ChatGPT to a T.

You might be interested in how ChatGPT did with Calloway’s code itself:

https://chat.openai.com/share/b59aaac9-74ad-4751-aabb-014b162b6924