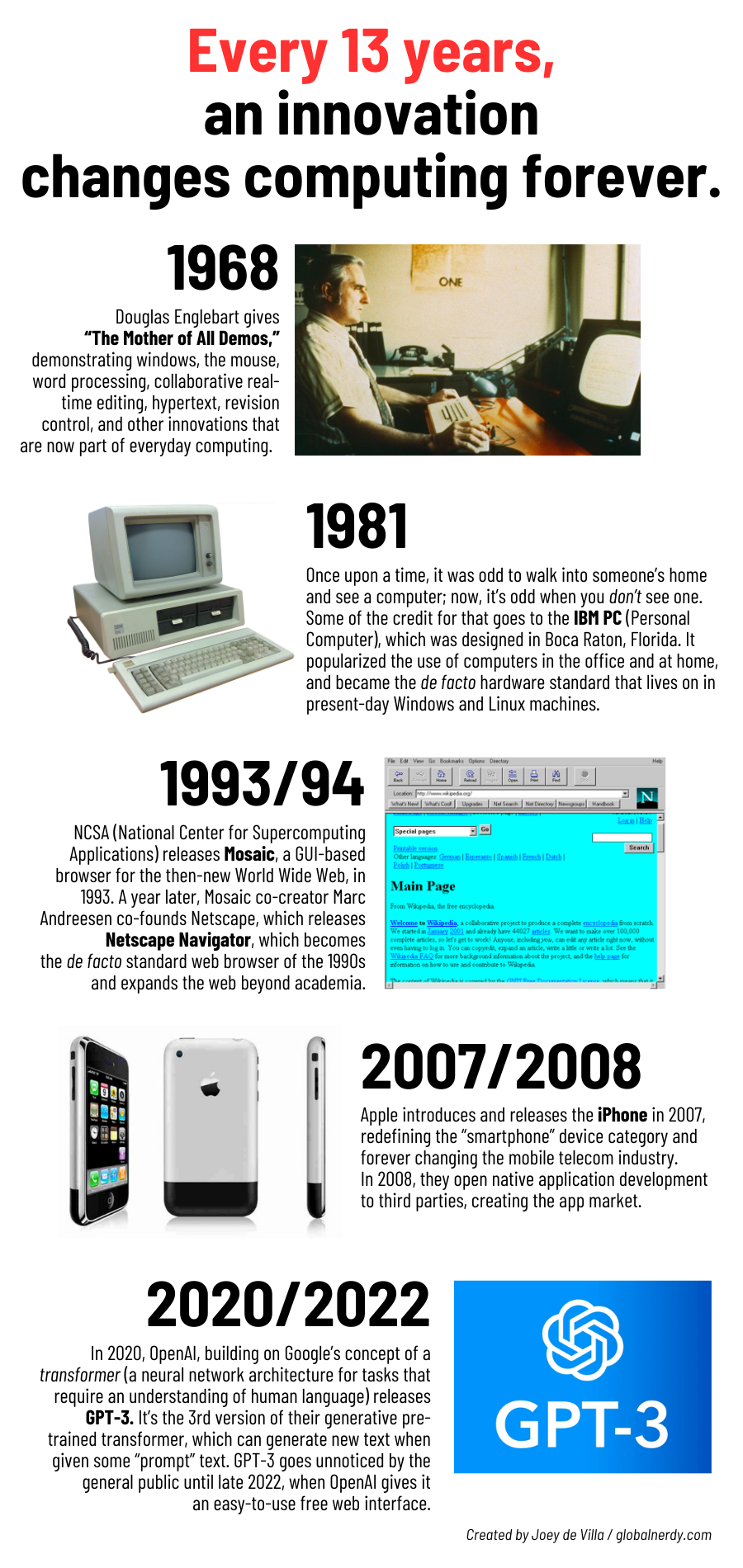

Almost exactly three years ago and about a month into the pandemic, Startup Digest Tampa Bay published my article where I suggested that the 2020 pandemic might be hiding some world-changing innovations that we didn’t notice because of everything going on, just as the 2008 downturn did.

My article, titled Reasons for startups to be optimistic, was based on journalist Thomas Friedman’s theory: that 2007 was “one of the single greatest technological inflection points since Gutenberg…and we all completely missed it.” It’s an idea that he put forth in What the hell happened in 2007?, the second chapter of his 2016 book, Thank You for Being Late.

In case you’re wondering what the hell happened around 2007:

- The short answer is “in the tech world, a lot.”

- The medium-sized answer is this list: Airbnb, Android, the App Store, Bitcoin, Chrome, data bandwidth dropped in cost and gained in speed, Dell’s return, DNA sequencing got much cheaper, energy tech got cheaper, GitHub, Hadoop, Intel introduce non-silicon material into its chips, the internet crossed a billion users, the iPhone, Kindle, Macs switched to Intel chips, Netflix, networking switches jumped in speed and capacity, Python 3, Shopify, Spotify, Twitter, VMWare, Watson, the Wii, and YouTube.

- You’ll find the long, detailed answer in my article. Go ahead, read it. What happened in 2007 and 2008 will astonish you.

It’s hard to spot a “golden age” when you’re living in it, and it may have been even more difficult to do so around 2007 and 2008 because of the distraction of the 2008 financial crisis.

In 2020 — 13 years after 2007 — we had the lockdowns and a general feeling of anxiety and isolation. I was about a week into unemployment when Murewa Olubela and Alex Abell approached me with an opportunity to write an article for Startup Digest Tampa Bay.

I took the optimistic approach, my preferred approach to life, and wrote about how there could very well be world-changing developments happening at that moment, and that we might not notice them because we were dealing with COVID-19, improvising masks and PPE, hoarding toilet paper and Clorox wipes, and binge-watching Tiger King.

When ChatGPT was released in late November 2022, I showed it to friends and family, telling them that its underlying “engine” had been around for a couple of years. The GPT-3 model was released in 2020, but it went unnoticed by the world at large until OpenAI gave it a nice, user-friendly web interface.

That’s what got me thinking about my thesis that 2020 might be the start of a new era of initially-unnoticed innovation. I started counting backwards: 2007 is 13 years before 2020. What’s 13 years before 2007?

1994. I remember that year clearly — I’d landed a job at a CD-ROM development shop, and was showing them something I’d seen at the Crazy Go Nuts University computer labs that had just made its way to personal computers: the browser, and more specifically, Netscape Navigator. What’s 13 years before 1994?

1981. That’s the year the IBM PC came out. While other desktop computers were already on the market — the Apple ][, Commodore PET, TRS-80 — this was the machine that put desktop computers in more offices and homes than any other. What’s 13 years before 1981?

1968. You don’t have any of the aforementioned innovations without the Mother of All Demos: Douglas Englebart’s demonstration of what you could do with computers, if they got powerful enough. He demonstrated the GUI, mouse, chording keyboard, word processing, hypertext, collaborative document editing, and revision control — and he did it Zoom-style, using a remote video setup!

With all that in mind, I created the infographic at the top of this article, showing the big leaps that have happened every 13 years since 1968.

If you’re feeling bad about having missed the opportunities of the desktop revolution, the internet revolution, or the smartphone revolution, consider this: It’s 1968, 1981, 1994, and 2007 all over again. We’re at the start of the AI revolution right now. What are you going to do?

Worth watching

The Mother of All Demos (1968): What Douglas Englebart demonstrates is everyday stuff now, but back when computers were rare and filled whole rooms, this was science fiction stuff:

The iPhone Stevenote (2007): Steve Jobs didn’t just introduce a category-defining device, he also gave a master class in presentations:

What the hell happened in 2007? (2017): Thomas Friedman puts a chapter from his book into lecture form and explains why 2007 may have been the single greatest tech inflection point:

Here’s the money quote from his lecture:

I think what happened in 2007 was an explosion of energy — a release of energy — into the hands of men, women, and machines the likes of which we have never seen, and it changed four kinds of power overnight.

It changed the power of one: what one person can do as a maker or breaker is a difference of degree; that’s a difference of kind. We have a president in America who can sit in his pajamas in the White House and tweet to a billion people around the world without an editor, a libel lawyer or a filter. But here’s what’s really scary: the head of ISIS can do the same from Raqqa province in Syria. The power of one has really changed.

The power of machines have changed. Machines are acquiring all five senses. We’ve never lived in a world where machines have all five senses. We crossed that line in February 2011, on of all places, a game show in America. The show called Jeopardy, and there were three contestants. Two were the all-time Jeopardy champions, and the third contestant simply went by his last name: Mr. Watson. Mr. Watson, of course, was an IBM computer. Mr. Watson passed on the first question, but he buzzed in before the two humans on the second question. The question was “It’s worn on the foot of a horse and used by a dealer in a casino.” And in under 2.5 second, Mr. Watson answered in perfect Jeopardy style, “What is a shoe?” And for the first time, a cognitive computer figured out a ton faster than a human. And the world kind of hasn’t been the same since.

It’s changed the power of many. We, as a collective, because we’ve got these amplified powers now, we are now the biggest forcing function on and in nature — which is why the new geological era is being named for us: the anthropocene.

And lastly, it changed the power of flows. Ideas now flow and circulate and change, at a pace we’ve never seen before. Six years ago, Barack Obama said marriage is between a man and a woman. Today, he says, bless it so, in my view marriage is between any two people who love each other. And he followed Ireland in that position! Ideas now flow and change and circulate at a speed never seen before.

Well, my view is that these four changes in power: they’re not changing your world; they’re reshaping your world, the world you’re going to go into. And they’re reshaping these five realms: politics, geopolitics, the workplace, ethics, and community.

Worth attending

Yup, I’m tooting my own horn here, but that’s one of the reasons why Global Nerdy exists! I’m the new organizer of Tampa Bay Artificial Intelligence Meetup, and it’s restarting with a number of hands-on workshops.

3 replies on “Computing innovations happen every 13 years, and we’re at the start of a new one”

[…] It’s an interesting idea that might be worth lining up with the one I had about cycles in computer innovations: […]

[…] I have a pet theory that every 13 years, a computing innovation appears and changes everything. (I basically summarized this theory in the presentation, and you can read about this in more detail in an earlier article of mine, Computing innovations happen every 13 years, and we’re at the start of a new one.) […]

[…] poster from May, titled Every 13 years, an innovation changes computing forever, theorizes that roughly every thirteen years, a new technology appears, and it changes the way we […]