The good news: Tampa Bay is the location of one of the biggest high-tech stories of the year!

The bad news: It’s because the breach that everyone calls the “Twitter Hack,” in which several verified accounts were used to scam people out of an estimated $100,000 in a single day, has been traced to a 17 year-old Tampa resident named Graham Ivan Clark. His story has been published in the New York Times article, From Minecraft Tricks to Twitter Hack: A Florida Teen’s Troubled Online Path.

The scam

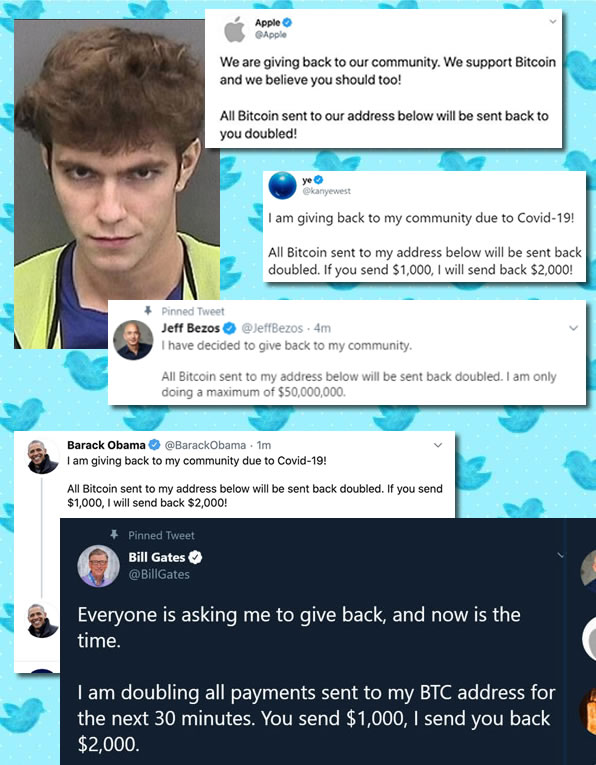

The scam involved hijacking the Twitter accounts of celebrities, politicians, businesspeople, and other “blue check” people and using them to post tweets like the one below:

It didn’t matter that offers to “double your money” from Jeff Bezos, Barack Obama, Kanye West, and Kim Kardashian were simply too good to be true, even with the appeal of “giving back” to help ameliorate the suffering caused by COVID-19. Enough people with enough disposable income to invest in cryptocurrency were fooled.

The exploit

In order to pull off the scam, he would need access to these “blue check” accounts. There are a handful of ways to do it:

- With Twitter, you can log in with your username (which is publicly known) and a password. A weak password — that is, one that’s easily guessed, or one of those lazy passwords that too many people use — makes for an easy target. This might work for accessing one or two accounts, but not for a lot of them.

- Exploiting some weakness in Twitter’s software or infrastructure to gain access to their system. In spite of the stories you hear about hackers, this is a high-effort, low probability-of-success scenario.

- Social engineering: Fooling or intimidating the people who run, administer, or maintain a system in order to get them to let you into that system, or provide enough useful information to do so.

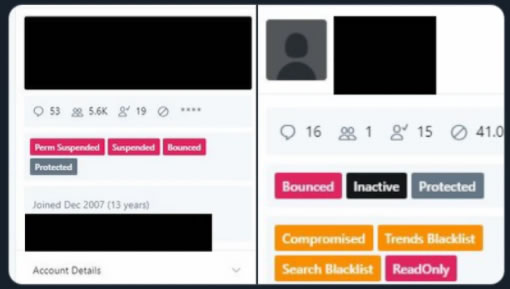

The initial reports indicate that Clark took the social engineering route and convinced someone at Twitter that he was a fellow employee, and as a result, got access to a customer service portal. Vice’s Motherboard posted some redacted screenshots of what this portal:

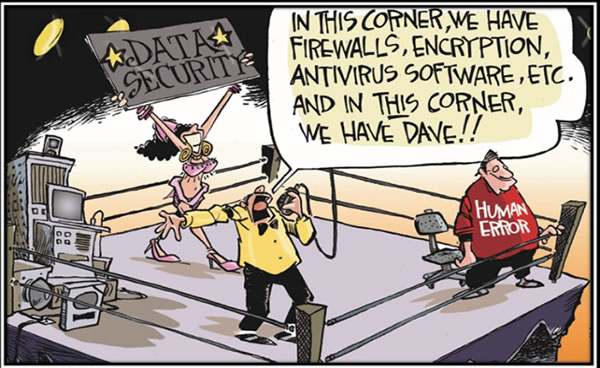

This shouldn’t be all that surprising — the human element is often the most “hackable” part of a system:

In the end, this scam is best described as “high-concept, low-skill.” In fact, the way they went about it has been described as “extremely sloppy.”

The Bitcoin addresses listed in the tweets turned out to be traceable to Coinbase accounts belonging to Clark’s accomplices, who registered them with their real driver’s licenses. One of them even did so from their home IP address, an amateur move that’s been a staple of computer heist movies and TV series since WarGames, and it was a key plot point in Hackers.

The NYT TLDR

You should read the New York Times piece on Clark, but if you want the highlights, here they are:

- He is 17 years old, a recent high school graduate, and he lived by himself.

- A Minecraft player since the age of 10, Clark became known as “as an adept scammer with an explosive temper who cheated people out of their money,” according to people who knew him.

- A former Minecraft friend said this of Clark: “I knew he really wanted money and he was never in the right mind-set. He would do anything for some money.” Another friend describes him this way: “He’d get mad mad. He had a thin patience.”

- Family life, as the NYT puts it: “Mr. Clark and his sister grew up in Tampa with their mother, Emiliya Clark, a Russian immigrant who holds certifications to work as a facialist and as a real estate broker. Reached at her home, his mother declined to comment. His father lives in Indiana, according to public documents; he did not return a request for comment. His parents divorced when he was 7.”

- In 2016, he played in Hardcore Factions — Minecraft with PvP and all the baggage that goes along with it — and built a YouTube audience while doing so. He also scammed fellow Minecraft players: “One tactic used by Mr. Clark was appearing to sell desirable user names for Minecraft and then not actually providing the buyer with that user name. He also offered to sell capes for Minecraft characters, but sometimes vanished after other players sent him money.”

- Under the handle “Open”, he gained a reputation for being “a scammer, a liar, a DDOSer”:

- Of course, he eventually migrated to Fortnite.

- Around the same time, he joined the OGUsers forum. The NYT: “His OGUsers account was registered from the same internet protocol address in Tampa that had been attached to his Minecraft accounts, according to research done for The Times by the online forensics firm Echosec.” On OGUsers, he also disappointed customers by failing to meet his end of the bargain after being paid.

- Want to guess where in Tampa he lives? The NYT posted this photo of his apartment. Let’s see if any of you have good satellite image/map image search-fu:

(My guess is Wesley Chapel, judging from the architecture, artificial lake, and the availability of “stroads” in which to open up the throttle on his BMW. What do you think?)

- He moved from Minecraft to Bitcoin.

- He was also into SIM swapping, again to relieve victims of their cryptocurrency. Last year, he was involved in the theft of almost $900K worth of Bitcoin, when hackers SIM swapped the phone of a Seattle tech investor. By doing so, they gained access to several of the investor’s accounts. Clark was one of them. Despite being caught by the Secret Service, he wasn’t arrested because he was a minor.

- He made enough money to live in an apartment by himself, drive a BMW 3 series, maintain an expensive gaming setup, and own a gem-encrusted Rolex.

Local news could use some local techie help

In my old home town of Toronto, whenever a story like this broke out, the local news stations went to the tech community to get background information. I was often one of those community members consulted:

Unfortunately, there isn’t such an arrangement here in Tampa, so local news’ coverage has had me rolling my eyes. I suppose it made for some good entertainment:

Maybe we Tampa Bay techies need to get on their radar and become go-to people for information when stories like this arise.

At the very least, local news should have The Undercroft on speed dial to provide some much-need background info and context when the story’s about a system being compromised.

At the very least, local news should have The Undercroft on speed dial to provide some much-need background info and context when the story’s about a system being compromised.