The opportunity

I first became aware of opening for a “Senior R&D Content Engineer” at Auth0 on August 18th. You can see the job description here.

I first became aware of opening for a “Senior R&D Content Engineer” at Auth0 on August 18th. You can see the job description here.

I did my research — because of course I did my research — and Auth0 turned out to be a very interesting opportunity for a number of reasons:

- The position leans heavily on two skills that I have that aren’t seen in the same person that often: Programming and communications. I have lots of experience in these areas, and can bring my “A” game to the position.

- Auth0 is in a business that is hot: Systems and information security, which is in demand as computing and networking becomes increasingly ubiquitous. The attractiveness of a hot business is obvious.

- Auth0 is also in a business that is boring: To put it a little too simply, Auth0 is in the business of logins, which doesn’t sound terribly exciting. Here’s where things get counterintuitive — why would I want to get into a boring business? Partly because of an idea from entrepreneur and NYU marketing prof Scott Galloway, which is that boring businesses make money. It’s also an idea of mine, which is that “boring” businesses produce essential products and services. And in a world where identity and access control are crucial, and identity and access control service is essential. I’m all for this kind of boredom.

- Auth0 is one of the standouts in a field with a few key players. There’s the companies that specialize in identity and authorization, such as Okta and Ping Identity, and then there are the giants such as Microsoft, IBM, and Oracle. If the 2019 Gartner Magic Quadrant for Access Management is to believed (and you should always read these graphs with some healthy skepticism), it’s at the top of the “Visionaries” quadrant:

Everyone in the desirable top right quadrant, “Leaders”, is either an old guard fingers-in-every-tech-pie company (IBM, Microsoft, Oracle), or has been in the identity/access business for over a decade (Okta was founded in 2009; Ping Identity goes back to 2002 — when there were iPods, and they had click-wheels). Auth0 was founded in 2013, and of all the up-and-comers in its space, it’s at the top. That means room to grow, opportunities to apply my talents, and a chance to shine.

- Auth0’s approach is developer-first. Authentication and authorization should be almost invisible for users; what they really care about is the application or service for which the authentication and authorization is the gatekeeper. It’s the developers who really have to worry about authorization and authentication, and that’s why Auth0’s focus is on developers. Not only is the platform developer-focused, but they devote a lot of time and energy into educating developers — and not just about Auth0, but identity topics, and even programming in general.

- Auth0 is remote work-friendly. When CEO Eugenio Pace and CTO Matias Woloski started Auth0, they did so while 7,000 miles apart. They’ve kept it up to this day, while people working from all over the world.

- Auth0 has a 4.8 out of 5 rating on Glassdoor based on 90 reviews. While Glassdoor ratings should be taken with a grain of salt, it’s a good sign.

- Auth0 is growing. They grew 70% in 2019, and in spite of the current economic situation, they’re still growing in 2020.

-

Tap to read the Auth0 article “So You Want to be a Unicorn?” Finally, as of May 2019, Auth0 is a unicorn. I’m using the term “unicorn” in the sense of “privately-help startup company valued at $1 billion or more.” They closed $103 million in Series E funding in May 2019, which pushed them past the $1 gigabuck mark, and closed an additional $120 million in Series F funding in July 2020, bringing the company’s valuation to just shy of 2 gigabucks. They’re a duocorn now! I want in on some of that action.

Crush the funnel

I combed my way through the most recent two years of the Auth0 blog and found two very useful articles:

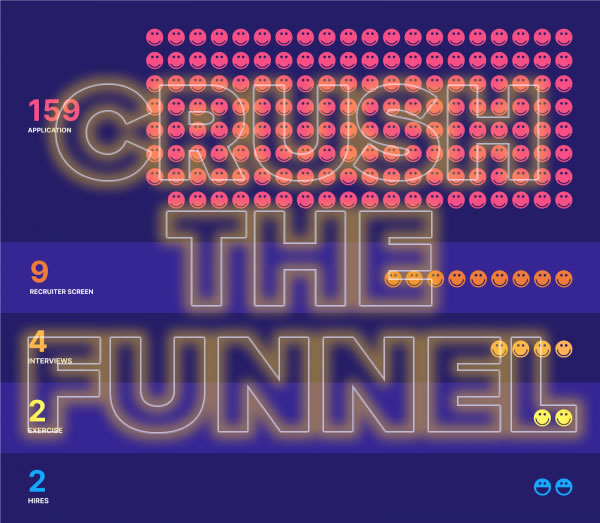

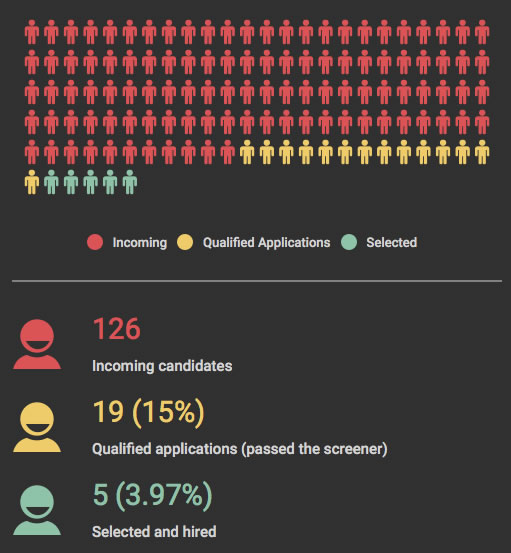

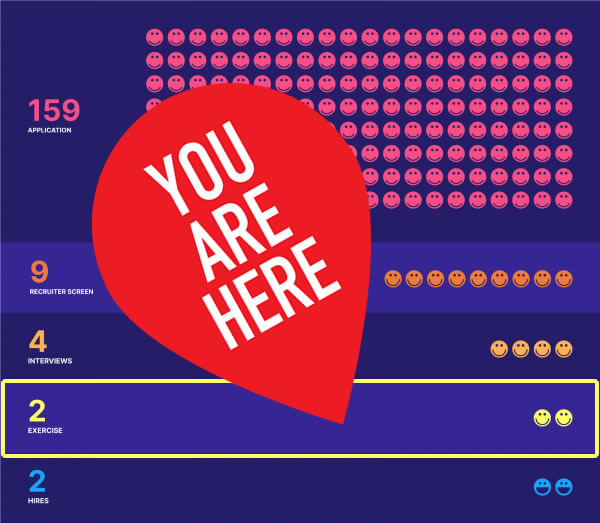

These two articles gave me a lot of useful information about what it would take to land a job there: Namely, a focused effort, the willingness to run through a series of gauntlets, as pictured below…

…and being ready to put in the energy to face their hiring funnel.

Here’s one depiction of the funnel, from their first “How We Hire Engineers” article:

Here’s a revised version, from a few months later:

The numbers above aren’t for the position I applied for, but for other Senior Engineer positions.

I really wanted this job. In order to beat these odds, my number one priority for the six weeks to come was to crush this funnel.

Step 0: Sending in an application

This is a software-as-a-service company, and in the time honored tradition of indexing in software, the first step was Step 0! This involved filling out an application form and including the following “cover letter” which was actually a large text area on the application form.

Applicants were encouraged to explain why they should be considered for the job. I first wrote it in a text editor, saved it for my records, and pasted it into the form. Here’s what it said:

I’m a technical evangelist, developer, and tech community builder, and I would love to help Auth0 make the internet safer as a Senior R&D Content Engineer!

I have a long history of helping both techies and laypeople make sense of technology in many ways: As a technology conference organizer, an author, a presenter, and in running technical meetup groups. I even had my own technology show for children, complete with puppet co-host.

Even though COVID-19 caused my last job to evaporate, I’ve managed to keep busy:

- I’ve spent the past five weeks in the inaugural cohort of the “UC Baseline” cybersecurity program offered by Tampa Bay’s security guild, The Undercroft. All the instructors will attest to my ability to not just absorb new material, but to communicate, cooperate, and share knowledge with others.

- I’ve also been teaching an introductory Python course on behalf of Computer Coach Training Center. There was local demand for this course, but they didn’t have any Python instructors. They contacted me, having see my blog and recent presentations on game development in Python and Ren’Py.

- Finally, I made revisions for the 2020 edition of the book iOS Apprentice, which teaches iOS app development by walking the reader through the process of writing four iPhone/iPad apps. I co-wrote the 2019 edition with Eli Ganim for RayWenderlich.com, and it spans 1500 pages.

In addition to this recent work, I’ve also done the following:

- I’m the editor and author of Global Nerdy, a technology blog that I’ve written since 2006. It has nearly 4,000 articles and over 9 million pageviews. It’s also the home of the weekly Tampa Bay Tech, Entrepreneur, and Nerd Events mailing list, which I maintain.

- I’m the author/developer/presenter for the video tutorial Beginning ARKit, which teaches augmented reality application development by writing four ARKit-based iPhone/iPad apps.

- I was the top-rated presenter at the RWDevCon 2018 mobile developer tutorial conference, where I gave both a four-hour workshop and a two-hour presentation on augmented reality programming for iOS with ARKit.

I have years of experience in technical communications and instruction, having done the following:

- Provided wide-ranging partner and developer training as a Developer Evangelist at Microsoft, from providing presentations to partners, to writing articles and editing the Canadian edition of MSDN Flash to running hackathons, giving presentations, organizing conferences, and doing interviews with technology media. I was also Microsoft Canada’s most prolific blogger.

- At GSG, I worked closely with their biggest partner, IBM, to help develop both the technical documentation and marketing messaging for their Network Infrastructure Cost Optimization offering, including writing, producing and narrating the promotional video.

- Provided technical expertise to SMARTRAC’s partners as they used the Smart Cosmos platform and SMARTRAC RFID technology to keep track of goods and physical assets as they are manufactured, shipped, and sold.

I’m an active participant in the Tampa Bay tech scene. I’m part of the organizing teams behind BarCamp Tampa Bay and Ignite Tampa Bay (my 2015 Ignite talk was included in the “Best Of” list), my blog posts are included as a regular part of the Tampa Bay Tech newsfeed, and I was part of the Tampa Bay team to made it to the finals at Startup Bus 2019.

Whenever someone asks me for advice about identity or authenticating and authorizing users in their applications, my stock answer is “Go with Auth0. They’ve already figured out the hard stuff.” With my unusual skill set and experience, I could do that in a more in-depth way at Auth0 as Senior R&D Content Engineer.

Step 1: A phone conversation with Wendy from the People Team

The application must’ve worked, because I made it to Step 1, the “recuriter screener” phase, where I talked to Wendy Galbreath from the People Team. As the Auth0 blog puts it, it wasn’t a tech interview, but “a high-level conversation about my experience — especially with remote work, interest in Auth0, the role and expectations.”

As I blogged that day:

All dressed up for a 📱 PHONE ☎️ interview. Sure, they won’t know I’m dressed up, but I’LL KNOW.

The interview itself took about a half hour, and I did about 90 minutes of prep beforehand, looking into at the Auth0 site, checking recent news about the company, and reviewing Wendy’s LinkedIn profile.

She went into detail about the perks of working for Auth0, which further reinforced my desire to join, and I told her about my background and work experience, and why I thought I’d be a valuable addition to the team, using my best “radio voice” while doing so.

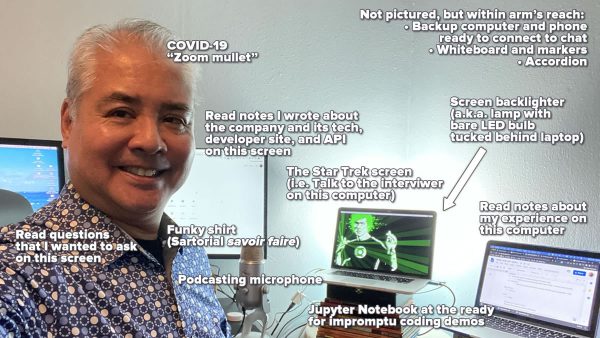

Step 2: Zoom interview with Tony, Head of Content

I passed Step 0, which meant that three days later, I had a zoom conversation with Tony Poza, Auth0’s Head of Content. This conversation was a little more technical, where I talked about my experience developing software, overseeing the development of software, doing developer evangelism, and creating content.

This interview was just over an hour, and I did around 4 hours’ worth of prep and background reading, including the Auth0 documentation, articles on their developer blog, and looking into the OAuth2 protocol, which Auth0 uses.

I enjoyed talking with Tony, and the interview only made me want to work at Auth0 even more.

Step 3: Zoom interview with Holly and Dan, two Senior Engineers

I passed that second interview, so it was time for another Zoom conversation, this time with Senior R&D Content Engineers Holly Lloyd and Dan Arias. If hired, I’d be working with them every day, so it was in their best interest to get a better feel for who I am, what I can do, and if working with me would be a good experience.

This interview was also a shade over an hour, and I’d done around 8 hours’ worth of prep, background reading, and some noodling with Auth0 and Python.

The conversation was a lot of fun, and I left it thinking Yes, I can definitely work with this team.

Step 4: Technical exercise — article + code

I’ll admit without any shame that by this point, I was checking my email very regularly for messages from Auth0.

I didn’t have to wait long. Hours after the Step 3 interview, I’d been notified that I had moved to the Step 4: The technical exercise!

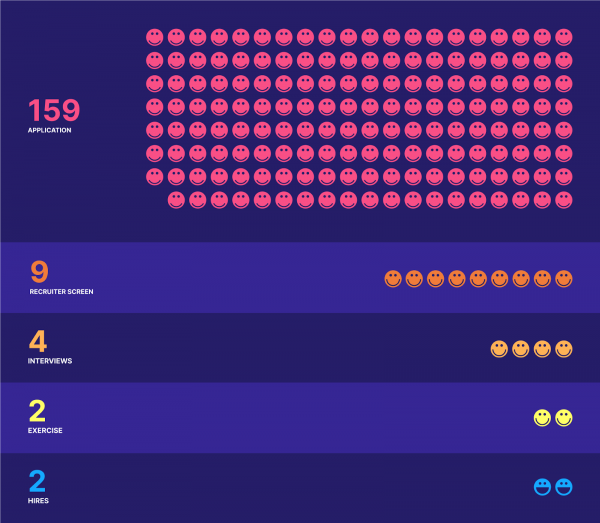

I was now at this point of the funnel:

This was a good place to be. With the major interviews done, passing was no longer subject to the vagaries of me having an off day or one of the interviewers being in a bad or at least unreceptive mood. This stage is all about proving that I could do the job and do so while working with my prospective teammates.

Most other engineering candidates at Auth0 are being hired to build, fix, or maintain the Auth0 service, so it makes sense that their exercise is to build some kind of technical project and then present it in a “demo call”, where they walk the interviewer through the project, explain their design decisions, and demonstrate the working solution.

As an R&D Content engineering candidate, my primary work output won’t be software, but content — documentation, instructions, articles, guides, and other material of that sort. My assignment was to write a “how to” article and the accompanying project. The idea is to showcase things like:

- Problem-solving and data sourcing technique

- Resourcefulness

- Writing and language proficiency

- Attention to detail

- Creativity

The assignment: Create a tutorial blog post explaining how to build and secure an API with Spring Boot, Kotlin, and Auth0.

My first thoughts:

- Securing an API with Auth0. That makes sense.

- Kotlin — nice! That’s definitely in my wheelhouse.

- Spring Boot? I know what Spring is, and have made a career out of avoiding it. What the hell is Spring Boot?

Since the exercise is partly a test of creativity, I was free to determine the kind of API that the reader of the tutorial would build. I thought I’d make it fun:

It was an API for a catalog of hot sauces. For the benefit of the curious, here’s a summary:

| API endpoint | Description |

|---|---|

GET api/hotsauces/test |

Simply returns the text **Yup, it works!** |

GET api/hotsauces |

Returns the entire collection of hot sauces. Accepts these optional parameters:

|

GET api/hotsauces/{id} |

Returns the hot sauce with the given id. |

GET api/hotsauces/count |

Returns the number of hot sauces. |

POST api/hotsauce |

Adds the hot sauce (provided in the request). |

PUT api/hotsauces/{id} |

Edits the hot sauce with the given id and saves the edited hot sauce. |

DELETE api/hotsauces/{id} |

Deletes the hot sauce with the given id. |

The article I wrote first walked the reader through the process of building the API. Once built, it then showed the reader how to secure it so that the endpoints for CRUD operations require authentication, while the “is this thing on?” endpoint remained public.

![]()

I wasn’t alone during the exercise. They set up a Slack channel to keep me in touch with the team I was hoping to join, and it’s standard procedure to assign you a “go-to” person (Dan was mine). I maintained a good back-and-forth with them, keeping them apprised of my progress, asking questions, and once or twice even sharing photos of what I was making for dinner.

While they said I could take as long as I felt I needed to complete the project, I figured that I needed to keep a balance between:

- giving myself enough time to handle all the unknowns and deliver a finely-honed article and accompanying project, and

- not taking so long that I end up being disqualified. As Steve Jobs put it so succinctly: Real artists ship.

On Day 2 of the project, while I was deep into working out how to use Spring Boot, a house down the street got connected to Frontier fiber internet. In the process, our house got disconnected. Luckily, I saw the truck down the street and straightened things out with the tech while he was still there.

I spent one Saturday working on the project with my computer tethered to my phone. Had I not caught the tech in time, the soonest I’d have been able to get someone to reconnect me would’ve been on Wednesday, a good four days later.

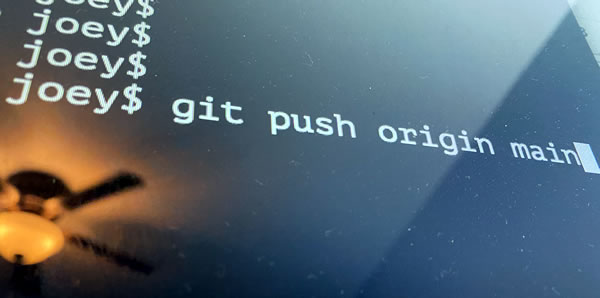

There came a point when I decided that the exercise was done and ready for evaluation. I made my final push to the repo and notified the team on Slack:

@channel I’d like to extend my most heartfelt thanks to everyone for this opportunity. It’s been fun, and I learned quite a bit in the process! As always, if there are any questions that you’d like me to answer, or anything else I can do for you, please let me know.

And then it was time to sit and wait. I checked Slack and my email a lot over those couple of days.

Step 5: BOSS FIGHT!

(Actually, an interview with Jarod, Director of Developer Relations)

I got an email three days later — a Friday afternoon — asking if I would be up for a last-minute Zoom interview with Jarod Reyes, Director of Developer Relations, who came to Auth0 in June from Twilio, where he was the Developer Evangelism Manager.

Naturally, I made myself available, and Step 5 took place late that afternoon, only a couple of hours after I got the email.

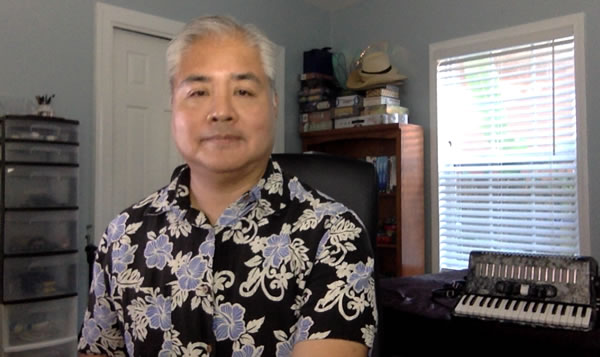

The webcam lights I’d ordered had arrived earlier that day, so I set them up quickly…

…and I had just enough time to do a quick screen test for the interview. And yes, the accordion didn’t just happen to be there; it was strategically placed in the shot:

The interview was friendly, brief, and half of it consisted of me asking Jarod questions about his plans for developer evangelism and content at Auth0.

With the call done, the weekend began. It’s been a while since I’ve impatiently waited for Monday to come around.

Step 6: The offer letter

Monday, September 28th: I checked my email a lot, and at 1:15 p.m., this message arrived:

Monday, September 28th: I checked my email a lot, and at 1:15 p.m., this message arrived:

Great news!

The team would like to extend an offer for you to join Auth0! Please let me know your availability today for a call so that I can share the details with you.

T minus one week

It’s been two weeks since I got the offer letter. Since then, I’ve signed it, filled out the standard paperwork, and even received the dongle for my company-issued MacBook Pro:

There’ve been some longer-than-usual shipping times for Apple products lately, but I’m not too bothered by that. I’m very pleased that I’m in and excited to be back in the developer relations / content game again.

What does this mean for the Tampa Bay tech scene?

For starters, it means that Auth0, a unicorn and player in the security space, has an increased Tampa Bay presence. (I’m not the only Auth0 employee, or “Auziro”, in the area.)

As part of the Developer Relations team, it’s my job to be part of the face that Auth0 presents to the developer community, and conversely, a way for the developer community to reach Auth0. I’m Tampa Bay’s “person on the inside”.

As a public-facing employee of a startup who service overlaps with security, I expect that I’ll be participating in local startup and security events — first virtual ones, and eventually, once we’ve all managed to control the pandemic, real-life ones.

And finally, as a public-facing Auth0 representative, as well as the writer of this blog and the Tampa Bay tech, entrepreneur, and nerd events list, I hope to represent Tampa Bay as an excellent place for techies to live, work, and play in.

Keep an eye on this blog, as well as the Auth0 blog! There are many interesting developments coming, especially if your interests are in software, startups, or security.