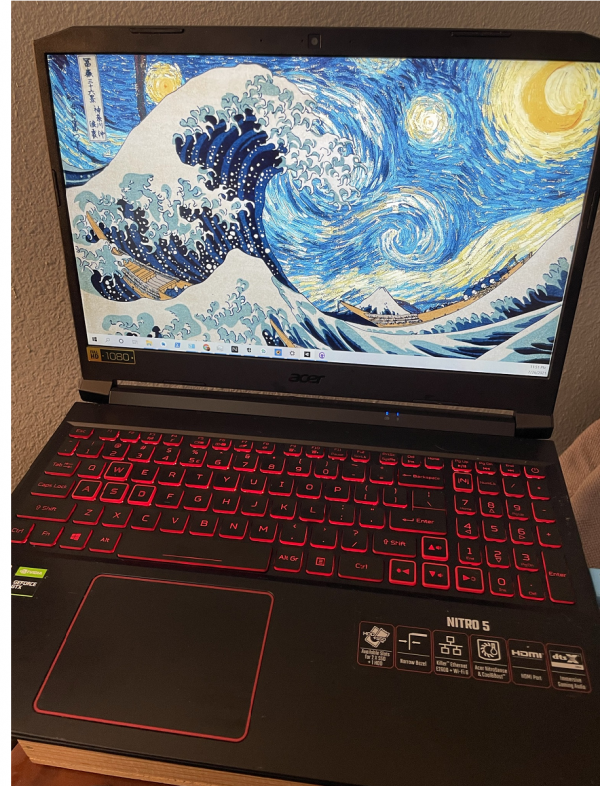

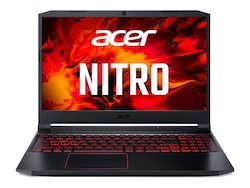

I have a new computer, or least one that’s new to me: An i5-powered 15″ 2020 edition of Acer’s “Nitro 5” budget gaming laptop, which I loaded up with 32GB of RAM. The grand total of my spending: US$600. I plan to use this machine (which is probably the most “dudebro” computer I have ever owned) mostly for CPU- and memory-thirsty developer stuff — Android, Flutter, Unity, Pygame, and machine learning — and mmmmmaybe just a little gaming here and there.

There have been times when either I or the scrappy startup where I was working was short on cash but needed one or more computers in short order. This problem was often solved with the judicious purchase of one or more used desktop or laptop computers. Secondhand machines offer lots of bang for the buck, but can be a dicey proposition if you’re not careful.

In this article, I’ll show you how to shop for a gently used machine that’s suitable for software development, will serve you for years to come, and will cost both you and the environment significantly less than buying a new one.

Why buy used?

The obvious reason is saving money, but it’s even more applicable these days because of the global chip shortage, which is a big enough deal to merit its own Wikipedia entry. As a result, inventories for any product with a chip in it have been drying up and prices have been climbing, especially where laptop computers are concerned. Here’s a quick sampling of some current news stories on the topic:

- Business Insider: Laptops and other gadgets are getting up to $50 more expensive because of the global chip shortage

- Marketwatch: The tiny, $1 chip that is behind record price increases for computers (June 17, 2021)

- ZDNet: Chip shortage will lead to higher PC prices as Dell, HP, and Lenovo pass on higher costs (May 28, 2021)

- Wired: The Chip Shortage Is Driving Up Tech Prices—Starting With TVs (May 13, 2021)

- The Guardian: Global shortage in computer chips ‘reaches crisis point’ (March 21, 2021)

Yes, the newest machines are quite often the fastest, most powerful, and have the latest features, but you have to ask yourself “How much of that do I actually need?” A computer with decent specs that was made sometime in the last few years can be a decent developer machine, or upgraded into one.

A secondhand computer is also a computer that’s not taking up space in our rapidly-growing junk piles. Let’s not contribute to our already huge e-waste problem — and when it’s time to really retire a machine, bring it to a place that recycles electronics!

(Hey, Tampa Bay techies: Your go-to place for electronic recycling is Urban E Recycling, who don’t charge for their service, and will even arrange to pick up your old gear.)

Why buy used and local?

Buying a used computer from someone in town has one major advantage: It gives you a chance to try it out before you buy it. Whether you’re buying from a store on an individual, you can look at it up close to check for wear and tear, confirm that all the keys and controls work properly, check to see that the ports are operational, and make sure that you’re about to buy a working unit.

There’s also a bigger-picture view: If you’re buying a used computer from someone local, you’re putting money back into the community, and more importantly, in the pocket of someone who needs it. If we really want to make Tampa Bay a tech hub and keep seeing stories about how techies are moving here and how we’re attracting technology workers in droves, we have to make the area a nice place in which to live. That means supporting the community — not just with lip service, but with what really helps: Your money.

Why buy used, local, and on Facebook Marketplace?

People have been buying used machines locally through Craigslist for nearly three decades, but these days, I’d rather buy stuff through Facebook Marketplace. It has a major advantage over Craigslist, and here’s what that advantage is:

Unlike Craigslist users, Facebook users have profiles. You can get a feel for the person you’re buying from or selling to, all before you even ask them a single question. You can see if they’re blank slates or people with an online history in words and pictures. You can even see what their friends are like. If they’ve sold on Facebook Marketplace before, they have a rating.

Facebook Marketplace also makes it quite easy to attach multiple photos for an item being sold, and provides you with a map of the general area where the seller is based. It also has the benefit of having a seller base that dwarfs Craigslist or any other platform.

While a Facebook profile isn’t a foolproof way for figuring out what kind of person is selling a used computer, it provides considerably more information than you’ll get from Craigslist before making contact.

Safety

I grew up in the era when teaching “stranger danger” was standard, so I was pretty amused when this joke started making the rounds:

In an age where it’s not unusual to get a ride or place to crash from a stranger, where the term “gig economy” is part of everyday parlance and everyone seems to have a side hustle, the idea of buying a used computer from a stranger doesn’t seem so weird anymore.

Still, as with Uber and Airbnb, you should take some safety precautions. Here are some recommendations from Yours Truly, who’s been buying stuff from local online people for twenty years:

- Meet in a well-lit public place with power outlets and wifi that can by used by customers. It’s just safer, if maybe a little inconvenient, to meet someplace where other people are rather than at their place or yours.

You’ll want to take the computer for a test run, which is why the meeting place must have power outlets and wifi that you can use. If you’re based in the U.S., consider using Starbucks or McDonalds for your meeting place; I’ll explain why these are good places to meet in a moment. If you’re fortunate enough to live in an area with a friendly independent “third place” (cafe, restaurant, or other business where people meet up) that has power and wifi handy — especially one where the staff know you — choose to meet there. - If you can, bring a friend along for the purchase. It’s a “safety in numbers” thing, and it’s even better when the friend has some expertise in the thing you’re buying. I’ve been “the friend” for these sort of purchases about a dozen times.

- See what kind on “data trail” the seller has. As I said beofre, one of the reasons I like Facebook Marketplace is that you can check the seller’s Facebook profile. Check other sources too — Twitter, and LinkedIn, and see if they participate in local Meetups. Get a feel for them, and trust your gut.

- See if you can pay using a payment app. Apps like Venmo, Cash App, and Zelle are relatively easy to set up, and it means that you’re not walking around with a big wad of cash.

- If you have to pay with cash, don’t break it out until it’s time to pay. Waving around the kind of money needed to buy a computer can attract the wrong kind of attention, so don’t break out the cash until it’s time to pay.

The computer that I’m replacing

I’ve had “Stinkpad”, my personal/side-hustle Wintel machine, for the past eight years. It’s a trusty ThinkPad T430, the most popular computer in the ThinkPad line, which which was first released in 2012, and which I got brand new in 2013. I’ve since replaced its dying hard drive and upgraded its RAM to the maximum 16 GB four years ago. Despite its age, it’s still a decent office computer (which you can still buy new from Walmart for $300).

Over the years, it has performed yeoman service as Windows/Linux development system, playing a key role in all my jobs based in the U.S., from a brief gig teaching Verizon developers how to program in C#, all the way up to teaching Python and JavaScript on behalf of Computer Coach during the pandemic and my current role as a Senior Developer Advocate at Auth0. In fact, I wrote much of the technical exercise project of the Auth0 job interview process on that computer (you can read all about it in How I landed my job at Auth0).

It’s still quite usable for putting together documents, surfing the web, watching streaming video, and even doing some basic web development, but as Android Studio, Unity, and other tools have grown, they’ve been demanding more processor power. I’m going to wipe ol’ Stinkpad clean and set it up for my in-laws, who are due for a new computer anyway.

I’d been keeping an eye on a specific marketplace (namely, Facebook Marketplace) for a specific kind of computer that appears every couple of months, almost like clockwork (namely, sub-$1000 gaming computers that are no more than a year or two old). They often come with the original packaging, were used very little, and are typically the object of buyer’s remorse. If you live in or near a reasonably large-ish metro area, don’t need a computer right away, and are willing to do a little legwork, you can find a good deal.

Research

Windows 11 compatibility

If you’re looking for a used Windows machine, you should keep compatibility with the upcoming Windows 11 in mind. Its installer will do a compatibility check prior to putting Windows 11 on your system, and if it doesn’t meet the operating system’s new, stricter standards, it will refuse to install.

It would take an entire article to cover what makes a computer Windows 11 compatible, so I’ll just give you the broad-stroke requirements and point you to a few articles that go deeper into the details.

Judging from the list of processors supported by Windows 11 (here are the lists of compatible AMD, Intel, and Qualcomm processors), a good general guide is that any computer manufactured in 2018 or later should be compatible. If you’re looking at Intel-based systems, 8th-generation or later chips will run Windows 11.

Microsoft provides these general Windows 11 hardware requirements:

- Minimum 4 GB RAM

- Minimum 64 GB “hard drive” storage

- TPM (Trusted Platform Module) 2.0

- Secure Boot-capable UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface)

- Graphics card compatible with DirectX 12 with WDDM (Windows Display Driver Model)

- A display that with at least 720p resolution, 8 bits per color channel

The computers I considered

Although I could get more power by choosing from desktops, portability is very important in my line of work, where I’m often doing presentations at different venues. That why I limited my search to laptops. I used to ignore gaming laptops, but the new-ish category of “budget gaming laptop” is turning into a great place to look for portable Windows-based developer machines.

Here are some computers that I considered buying:

This one is an HP Pavilion 16″ gaming laptop with a 10th-gen i5 CPU and NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1660 Ti GPU that the seller wanted $1000 for. It sells for $1000 brand new at Best Buy, but the seller upgraded the drive from 512 GB to 1TB, and the RAM from 8 GB to 16 GB. The seller has since reduced the asking price to $950.

It’s nice, but I decided to look around for a better deal.

If you’re in the Tampa area, are just getting started on your coding career, and need a good development machine, you might want to check out this deal on an MSI GP72 Leopard Pro gaming laptop, for which the seller is asking $400. It has great specs for that price: 7th-gen i7 CPU, NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1050 GPU, and 16GB RAM. This machine will move easily from React Native to Android Studio to GTA V, but the 7th-gen CPU rules out Windows 11 compatibility. It’s still a decent machine, especially for the price, but I wanted to see what I could get if I spent a little more.

The computer I went with

I did a double-take when I saw that someone a short drive away was selling a 2020 Acer Nitro 5 laptop. It appears on a number of “Best inexpensive gaming laptops” articles: PCMag’s, Laptop Magazine’s, Cnet, and TechRadar.

Like Loki, this laptop has many variants. Luckily for me, the seller was pretty good about posting the exact model number of the computer: AN515-55-55SD, which made it easy to look up its specs.

Here are the specs I cared about the most:

- Processor: Intel Core i5 10300H (10th generation) running at 2.5 GHz with 4 cores and 8 threads.

- Graphics: NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1650 with 4GB RAM.

- Memory: 8 GB DD4 RAM running at 2933 MHz, occupying one of two available slots. My plan was to replace it immediately.

- Storage: 512 GB Western Digital SN530 solid-state drive. I might replace this at some later date. The laptop also has an empty space for an additional 2.5″ drive.

Video reviews

I consulted a lot of reviews, including the following video reviews.

The most helpful and thorough video review was one by “Meanpooh”, who did a fantastic job covering a lot of details about the machine:

Also helpful: Hardware Canucks’ review:

Bonus: Filipino reviews!

If you understand Tagalog (Filipino) — or more accurately, “Taglish” (Tagalog peppered with a lot of English), you might find the video below helpful.

This first one is titled Ok ba ang presyo?, means “Is the price OK?”. He’s not so impressed by the Nitro 5, but keep in mind that he’s thinking of it primarily as a gaming machine, while I’m thinking of it as primarily for coding. He’s also keeping in mind that it sells for 50,000 Philippine pesos (about $1000 U.S.) when the average salary there is 860,000 pesos (about $17,200 U.S.) — or for the average Filipino, 6% of their salary.

Here’s one by Laptop Factory’s Dustin Kwan, who’s a little more impressed, as I am:

Pricing

The seller was asking $600 for their Acer Nitro 5. A quick look around showed that I’d be saving at least a third by buying from him rather than retail:

- $990 at Walmart for the 2021 editon, with the 11th generation of the CPU)

- $970 at Amazon

- $930 at NewEgg

- $800 at BJ’s Warehouse for the 2019 edition, with the 9th generation of the CPU

Inspection and purchase

The coffee trick (or: Why I recommend doing the inspection and purchase at McDonald’s, Starbucks, or your local cafe)

You’ll want time to properly inspect the computer, which means you’ll need to “buy some patience” from the seller. The reason I tend to hold the inspection and purchase session at places like McDonald’s, Starbucks, or a local cafe is so that I can buy the seller a coffee or snack. This will keep them occupied while you conduct a thorough inspection of the computer.

You want to spend at least 15 minutes with the computer running. This is enough time to get the computer up to its regular operating temperature and catch any sign that something is wrong with its hardware, such as the cursor turning into the “hourglass” or “beach ball” too often, or sudden restarts and freezes.

The inspection process

The process of inspecting a used computer could take up its own article, and perhaps I’ll write it up in more detail later.

I brought the following to help me with my inspection:

- Wired mouse

- USB-C-to-A adapter

- Wired earbuds

- HDMI cable

I’ll explain how I used each of these below.

Here’s a quick run-down of my inspection:

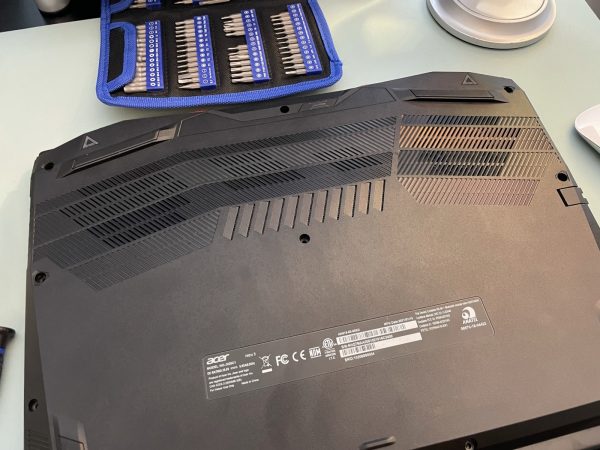

✅ Visual inspection of the chassis for scratches, dents, and other damage. I looked at the top, bottom, and sides for signs that the laptop had been dropped, or for excessive wear and tear around the ports.

✅ Visual inspection of screen for damage, scratches or dead pixels. With the laptop off, I checked for scratches on the screen using my phone’s flashlight. I checked for dead pixels by quickly entering the following into Notepad, saving it as test.html and opening the file in a browser in full-screen mode:

<html> <body style="background-color:yellow"> </html>

✅ Opening and closing the screen hinge. I opened and closed the screen a couple of times, checking to see that the motion was smooth and noiseless. This is a laptop’s biggest moving part, and it contains the connections between the main board and the screen, webcam, and often the microphone. You want to be sure that this hasn’t been damaged.

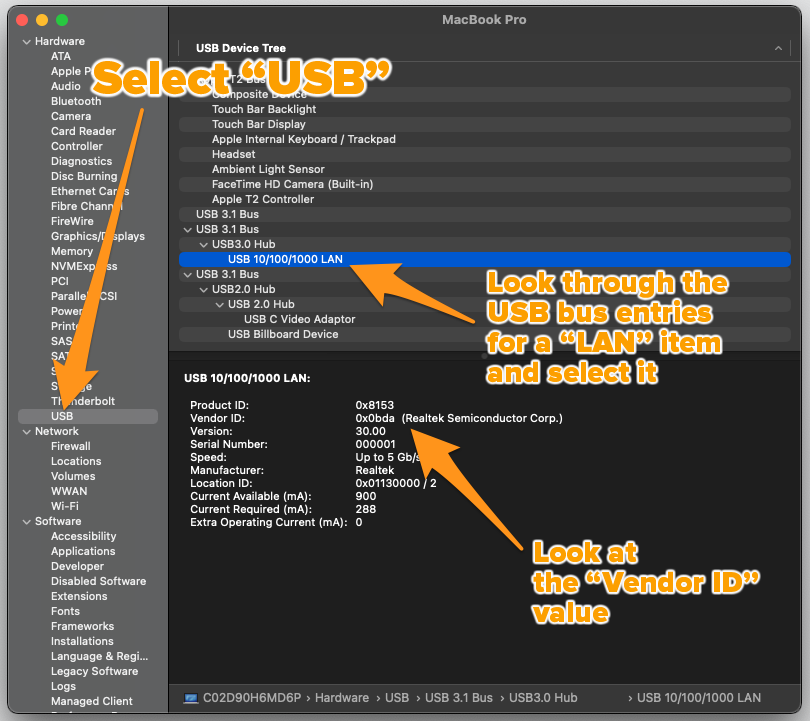

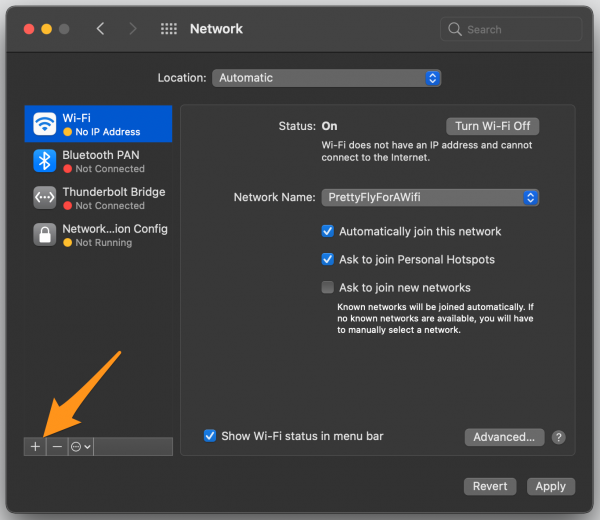

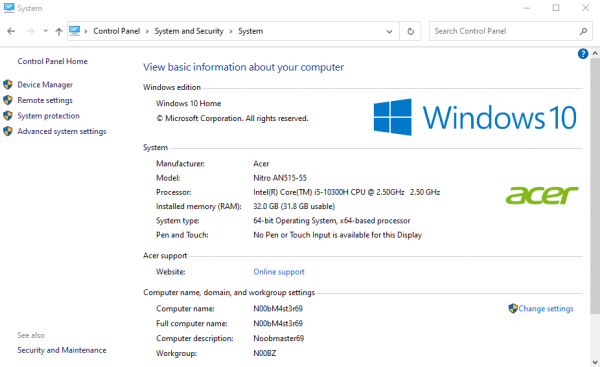

✅ Getting system information about the computer. On macOS, About This Mac is your friend. On Windows, System Information and Device Manager applications are your friends. They let you know what the computer thinks its specs are, and can point out any parts that might not be working or have missing drivers.

Use these utilities to check the processor in the computer as well as the installed RAM.

✅ Check the OS version. This is less important, as you should completely install a fresh copy of the OS if you buy the computer. For macOS, you should be concerned if the computer is running anything older than “Mojave” (macOS 10.14, released in September 2018). With Windows, be concerned if the computer is running anything pre-Windows 10.

✅ Check the system monitor. On Windows, you’ll want to open the Task Manager and open the Performance tab. On macOS, you’ll want to open the Activity Monitor app. In either case, you want to look at the CPU utlization when nothing other than a browser is running. If it’s significantly higher than 10%, something’s wrong — the CPU is laboring for reasons that can include malware.

✅ Keyboard. I opened Notepad and pressed on every key to confirm that they were all working. I checked the travel on every key to ensure that it was smooth. Sticky keys or “bouncy” ones (that’s where you press on a key once, but the character gets entered twice or more) are a sign that someone spilled liquid on the keyboard. I also confirmed that the metakeys (alt, ctrl, and shift) worked. They keys hadn’t been used much.

✅ Trackpad. I tested the trackpad for reponsiveness to regular “mouse” motions, as well as responses to swipes and clicks.

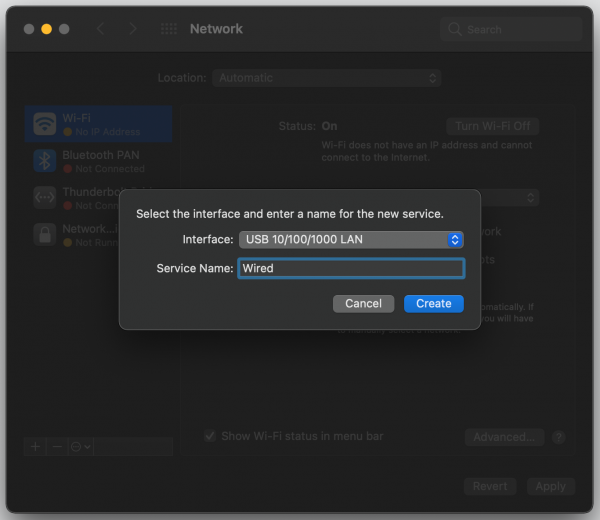

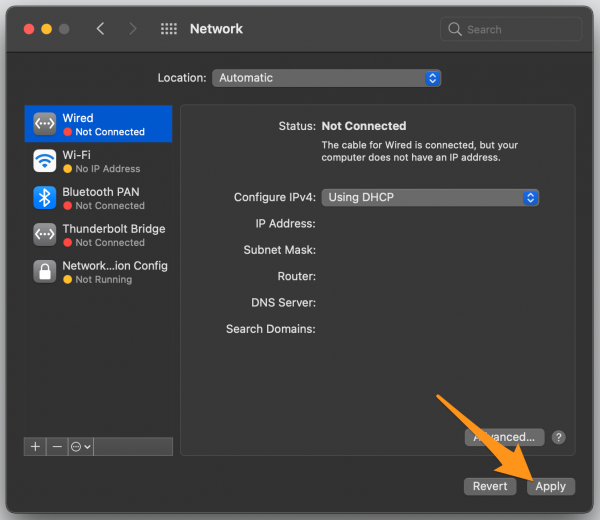

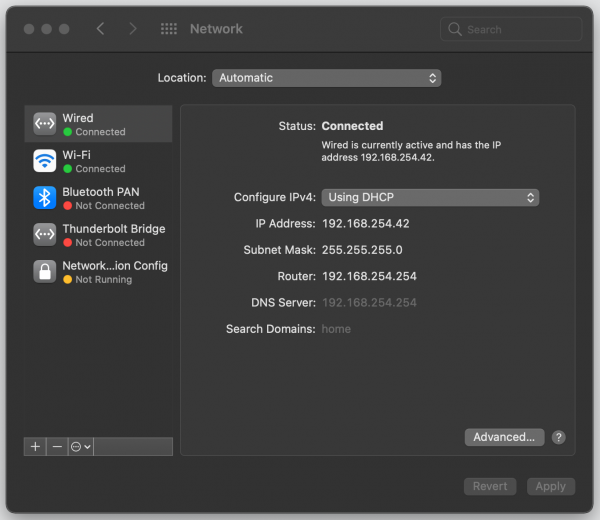

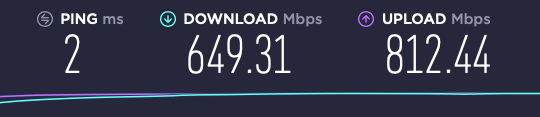

✅ Wifi. I connected to wifi and ran a speed test.

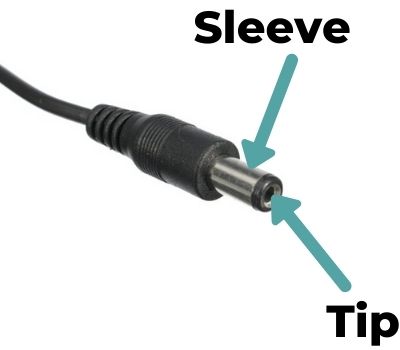

✅ USB ports. I brought a wired mouse to confirm that the USB ports were working. People may get concerned if you try and plug in a USB drive, but nobody objects to a mouse. I plugged the mouse into all the USB-A ports, and used a USB-A-to-C adapter to test the USB-C port. The fit in all these ports was tight, meaning that they hadn’t been used much.

✅ HDMI port. I brought an HDMI cable just to plug it into the port to confirm that it wasn’t damaged or obstructed. I should’ve borrowed my wife’s tablet-sized HDMI monitor, which fits easily into a laptop bag.

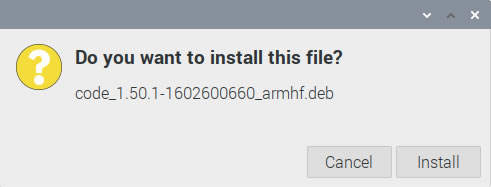

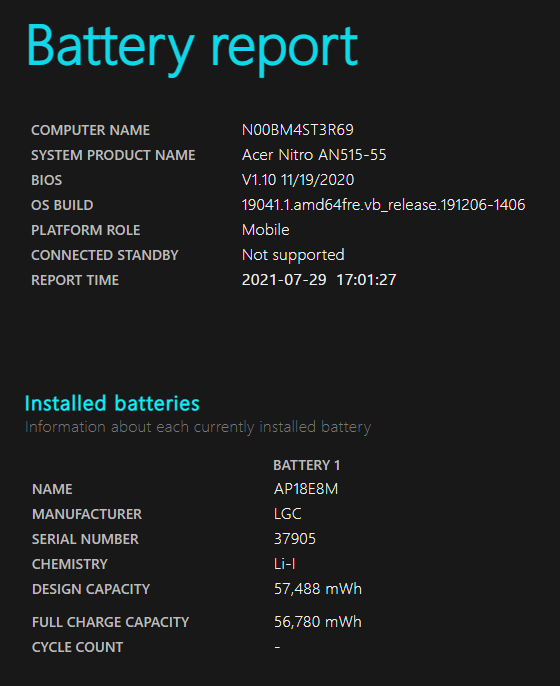

✅ Battery. I have such a low opinion of Windows battery management that I didn’t even bother to check the battery. When I use a laptop on a plane (and hopefully, that will happen again), I use a Mac. That being said. I should have opened up PowerShell and run the command powercfg /batteryreport. That runs Windows’ built-in battery reporting utility, which generates a report in web page form and saves it to your user directory. I ran the utility while writing this article, and here’s a screen capture of it:

As you can see from the report, the battery hasn’t been cycled very much — it can still charge up to 98.8% of its design capacity.

If you want to see battery info about a used Mac or iOS device, I recommend using the Coconut Battery app.

✅ Speakers. I simply opened a browser and pointed it a YouTube to confirm that the speakers were in working order.

✅ Headphone port. I brought a pair of wired earbuds with me. It turned out that the headphone port wasn’t working, but a quick look at Device Manager told me what I suspected: A driver was missing. One quick driver installation later, it worked.

✅ Run some apps. Run whatever applications are on the computer and look for unexpected slowdowns or other unusual behavior.

✅ Use your ears. Listen to the sounds that the computer makes. Do you hear a mechanical hard drive whirring? Be careful — these are slower, and being phased out. A mechanical hard drive can be used as a point for negotiating for a lower price. Listen for clicks or a grinding sound; both are indicators of a mechanical hard drive on its last legs.

Listen to the fans. Are they always spinning at top speed, or do they speed up or slow down as you start and stop using applications? Note that gamer laptops typically provide applications that let you control their fans, as their CPUs and GPUs tend to generate a lot of heat.

The only “hiccup” in my tests was the non-working headphone port, and that was resolved pretty quickly.

On the issue of money

💰 Ask for proof or purchase for the machine. If they can’t provide it, you’re going to have to make a judgement call on whether you still want to buy it or not. To be fair, I myself would be hard-pressed to find the receipt for the MacBook Pro I bought at the end of 2015, and the flea market guy who sold me my newest accordion didn’t give out receipts. But try to get that receipt.

💰 If you’re paying in cash, which I did in this case, count it out in front of them. Don’t rely on the seller to count it. There are all manner of sleight-of-hand tricks where a con artist can count bills and claim that you gave them less than you actually did.

Making it mine

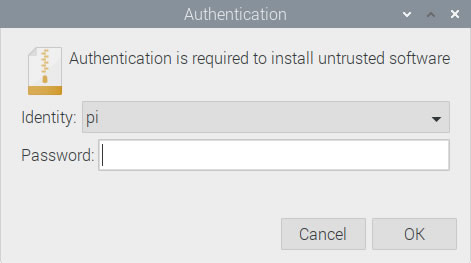

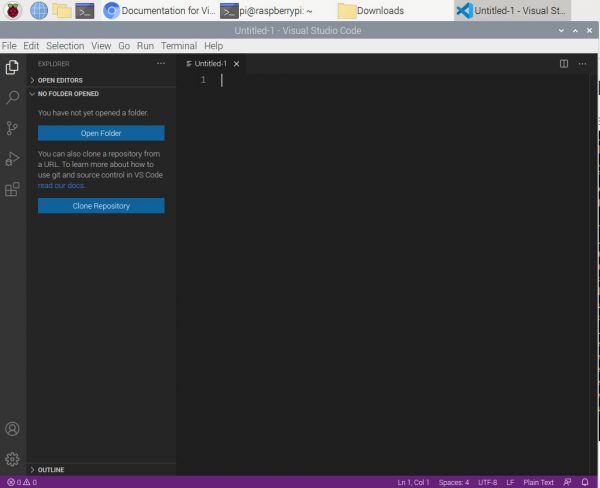

A fresh copy of Windows

I was lucky that the seller had all the drivers for the laptop gathered into a directory. I backed up that directory onto a cloud drive, and then “paved over” the hard drive with a fresh copy of Windows 10 from a disc image.

Once I’d installed Windows 10 and confirmed that it was running, I reinstalled the drivers.

Ordering and installing RAM

Tampa Bay isn’t like my old stomping grounds of Toronto, which seems to have plenty of little computer shops with all kinds of RAM on hand. On the other hand, it’s pretty close to an Amazon fulfillment center, who could deliver a 32 GB gaming RAM kit that afternoon. I had enough gift card points to get it for “free”.

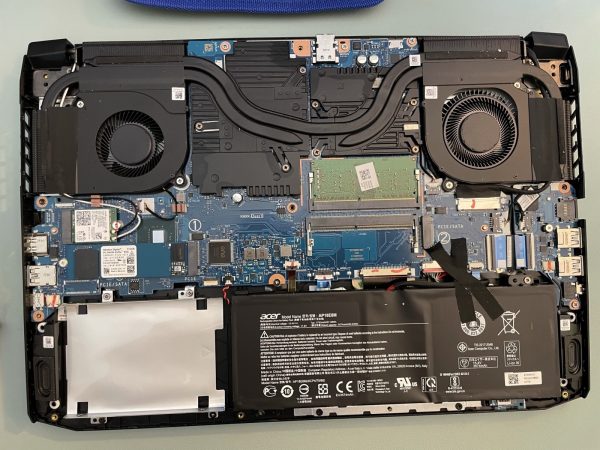

I placed the order at about 10:00 a.m., and the RAM arrived at my front door by 3:00 p.m.. I wasted no time in pulling out a precision Phillips screwdriver, a spudger, and an anti-static wrist strap and got to work.

I removed the screws from the bottom of the laptop pretty easily. The spudger came in handy for removing the bottom panel, as its fit is pretty tight.

The Nitro 5 has some pretty serious fans, as you can see. They’re controlled by Acer’s Nitrosense application:

Here’s the RAM I ordered: 2 16GB SODIMMs, which bring the laptop up to its maximum supported 32 GB of volatile memory:

I removed the original 8GB SODIMM and replaced it with the 2 16 GB ones. This was the simplest part of the process:

With the new RAM installed, it was time to fire up the computer, open the System application and confirm that the computer could access it. The operation was a success:

And now, it’s my primary Android / Flutter / Unity development machine!