One of the most common uses for smartphones is finding out where you are. According to a Pew report from September 2013, nearly three-quarters of adult smartphone users use their smartphones to get directions or other information based on their location.

At the heart of this functionality is GPS, the Global Positioning System, which is built into every smartphone and those tablets that are equipped to access cellular networks. Chances are that you’ve make some use of it, and we thought you might want to know how it works. In this article, we’ll explain GPS in layperson-friendly terms, and also give you some practical and not-so-practical tips on how to get the most out of it.

GPS constellations

The earth is surrounded by GPS satellites organized into a constellation. The basic design of the GPS system calls for a constellation divided into 6 different orbital planes, with 4 satellites per orbital plane, for a total of 24 satellites arranged the pattern shown below:

This arrangement ensures that no matter where you are on the planet, there will be at least four satellites in the sky above you.

We rely on the GPS system so much that there are more than 24 satellites in orbit; the additional ones provide additional accuracy and can be used as backup in case some satellites fail. At the time of this writing, there are 32 satellites in the GPS constellation, 31 of which are usable. You can find out how many GPS satellites are in the constellation at the moment by visiting the United States Naval Observatory’s Current GPS Constellation page and the constellation’s status with the Daily GPS Constellation Status page.

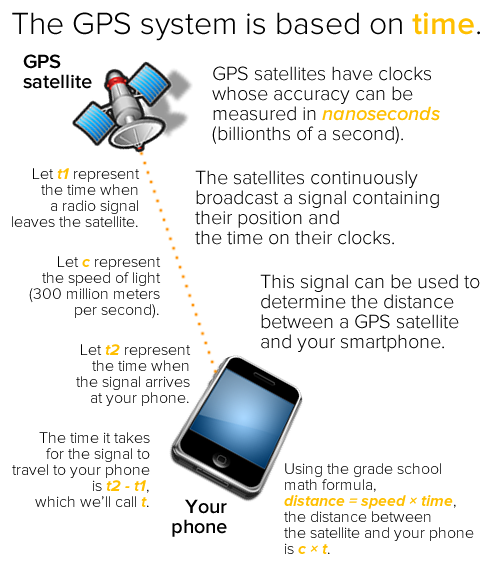

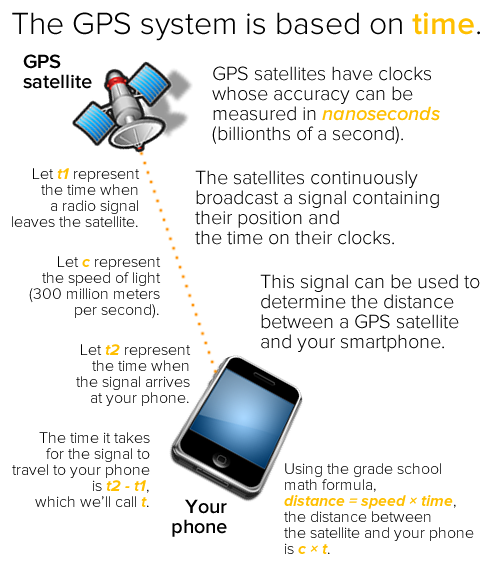

The GPS system is based on time and math you learned in grade school

The GPS system relies on time to measure distances. GPS satellites have onboard atomic clocks, which are the most accurate known time-keeping devices. Atomic clocks use the radiation emissions of a cesium isotope as a “pendulum” that “swings” about 9.2 billion times a second, providing nanosecond (billionth of a second, or 10-9 seconds) accuracy. A nanosecond happens so quickly that during its span, even light can’t get very far: just a little over 9 feet (a little under 3 meters).

With such a precise clock, you can use radio transmissions to measure distances using the grade school math formula distance = speed × time:

With the distances between itself and a small number of GPS satellites, your smartphone can quickly figure out your location.

How your smartphone uses its distance from GPS satellites to figure out your location

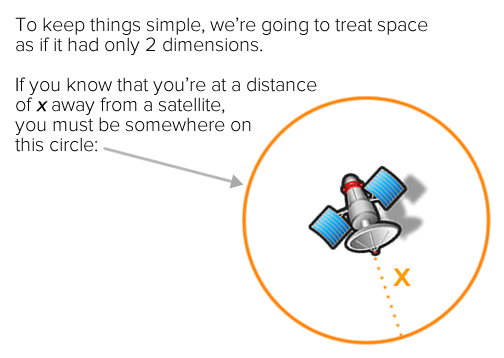

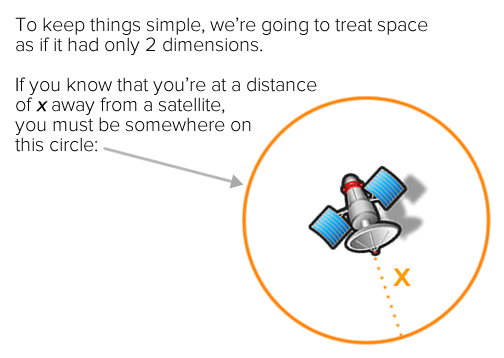

We’re going to keep the explanations simple, and won’t bog you down with a lot of math. We’ll do this by treating space as having only two dimensions rather than three.

If you know the distance between yourself and a single satellite — let’s call it x — you know that you’re somewhere on a circle of radius x with the satellite in the middle. That narrows down your possible location somewhat, but it’s not enough to figure out where you are:

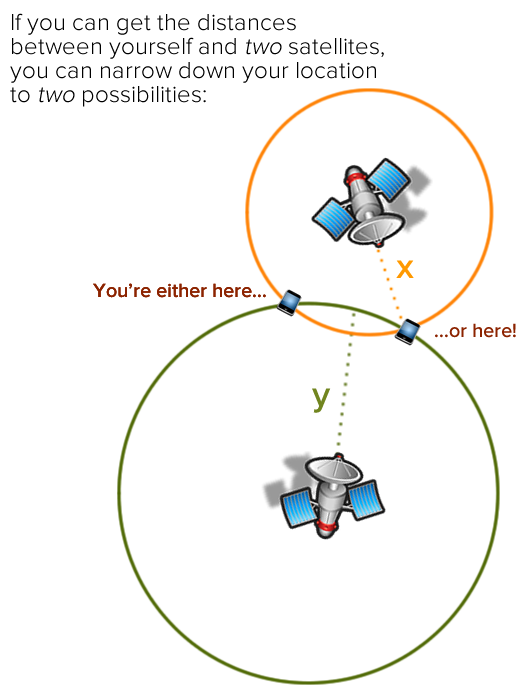

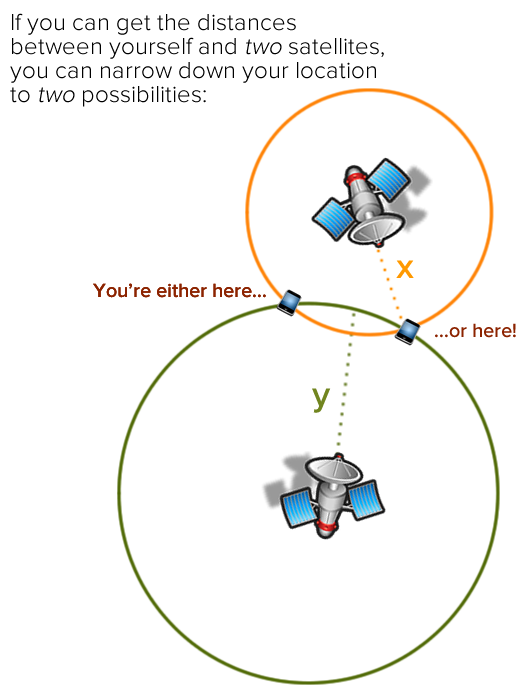

If you add another satellite to the mix and can get the distance between you and it — let’s call that distance y — you know that you’re also somewhere on a circle with a radius of y with that second satellite in the middle. Since you’re also on the circle of radius x, you must therefore be in one of the two places where both circles intersect. That narrows down the possibilities for your location considerably:

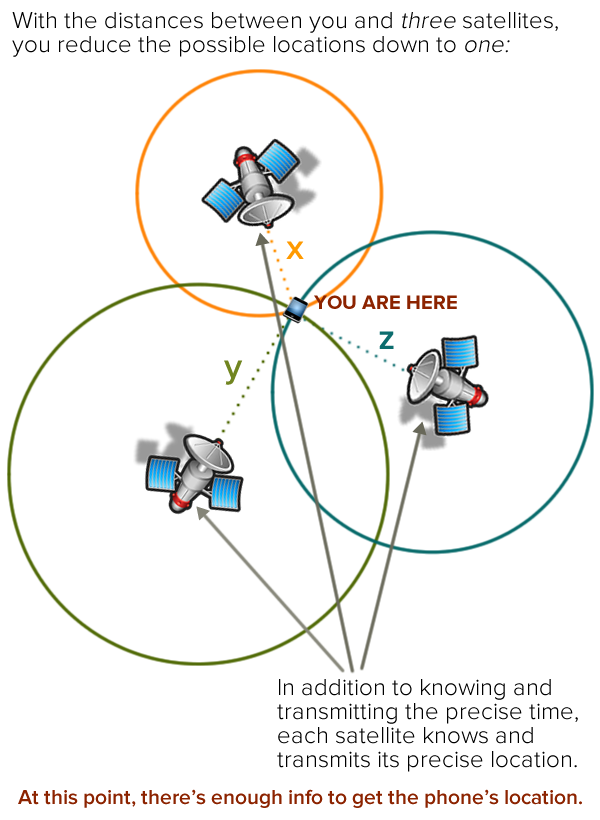

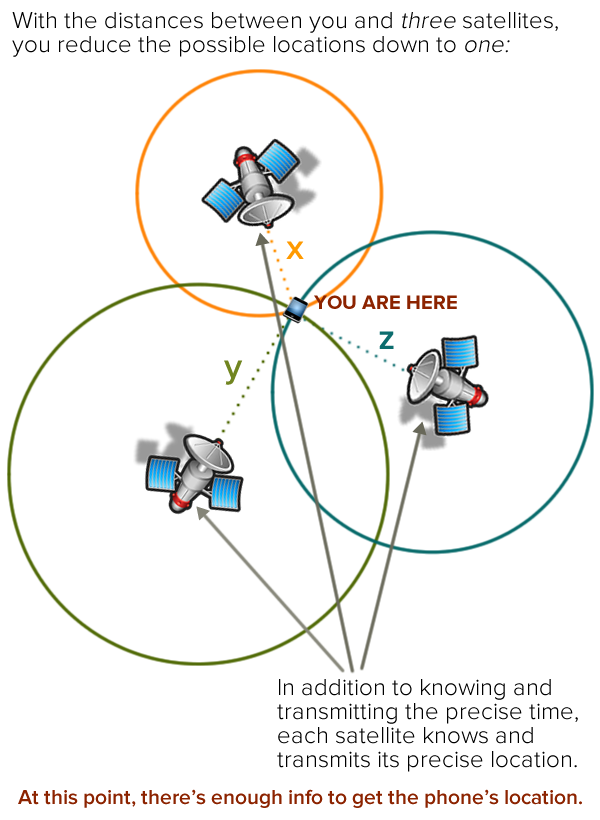

With a third satellite, you can perform trilateration, which narrows down your location to a single spot:

In case you were wondering, trilateration finds a location through the use of three distances. The term you’re probably more familiar with, triangulation, finds a location through the use of three angles.

Often, a fourth satellite is involved, and it serves two purposes:

- It’s needed to act as a reference for when the GPS signal arrived at your smartphone. Remember, in order to determine the distance between your smartphone and a satellite, you need to know the precise time when the signal arrived at your smartphone. Unfortunately, the clock on your smartphone isn’t anywhere as accurate as an atomic clock, so the GPS receiver in your smartphone uses the time broadcast from a fourth satellite as a reference clock to determine when the signals from the other three reached it.

- It increases location accuracy. Remember, in the diagrams above, we treated the earth as two-dimensional — that is, a flat surface — and required three distances to determine our location. In real three-dimensional space, we need four distances, which requires four satellites. However, with a little mathematical trickery that we won’t get into here, a GPS can get an approximate position with only three satellites.

Practical considerations

GPS alone doesn’t cost anything (unless you’re a U.S. taxpayer)

You may have noticed the cellular and internet networking aren’t mentioned in our explanation of how GPS works. Plain old GPS relies solely on the continuous, one-way signals broadcast by satellites and doesn’t need any cellular or internet data. Your smartphone doesn’t even send a request to a satellite to find its location, but simply listens to GPS’ always-on, always-available signals, in the same way you’d look for street signs and landmarks to get your bearings. As a result, using GPS by itself on your smartphone doesn’t eat into your data allotment or cost you any money…unless you’re a U.S. taxpayer.

You may have noticed the cellular and internet networking aren’t mentioned in our explanation of how GPS works. Plain old GPS relies solely on the continuous, one-way signals broadcast by satellites and doesn’t need any cellular or internet data. Your smartphone doesn’t even send a request to a satellite to find its location, but simply listens to GPS’ always-on, always-available signals, in the same way you’d look for street signs and landmarks to get your bearings. As a result, using GPS by itself on your smartphone doesn’t eat into your data allotment or cost you any money…unless you’re a U.S. taxpayer.

The GPS system was developed by the United States Air Force, who’ve maintained it for the past 20 years and provide it for free to everyone worldwide. If you pay taxes in the U.S., you’re footing the bill for GPS, and lost people everywhere thank you.

Maps use your data plan unless you use offline maps

The location data that you get from GPS — your latitude and longitude — are meaningless by themselves to most people. Usually, this data is paired with contextual information, such as a map from Google Maps, or a database of nearby locations from apps like Yelp, Starbucks, or GasBuddy. This contextual information comes from the internet, and if you’re getting it through your cellular connection rather than wifi, it’s using your allotted data, and you’re paying for it.

The location data that you get from GPS — your latitude and longitude — are meaningless by themselves to most people. Usually, this data is paired with contextual information, such as a map from Google Maps, or a database of nearby locations from apps like Yelp, Starbucks, or GasBuddy. This contextual information comes from the internet, and if you’re getting it through your cellular connection rather than wifi, it’s using your allotted data, and you’re paying for it.

If you use your smartphone as your navigation system and you’re driving long distances, your smartphone will download new map data as needed. If you’re on a limited plan, watch for this — this could be a big consumer of data.

If you use GPS often and are worried that your map use is eating into your data allotment, or if you’re using GPS while roaming, you should consider using offline maps. These are maps that are stored on your device, which means that it doesn’t have to use the internet to get them. As a result, you’re only using GPS to navigate, and not using any cellular data. Here are a couple of offline map options:

- The Google Maps app (free, available on the iOS App Store and Google Play) allows you to download and save maps for areas as large as 31 miles by 31 miles (50 km by 50 km). Here are the iOS instructions, and here are the Android instructions.

- MAPS.ME (free for the “lite” version) runs on iOS, Android, and BlackBerry. There’s a “lite” version that provides the basics for getting around, and a paid “pro” version that lets you search and bookmark locations.

- Galileo (free, available on the iOS App Store) is a good choice for iPhone and iPad users looking for a free offline map app.

- If you want a more full-featured map app, you should consider looking at paid apps. Wired recently reviewed a few of them: Sygic, Navmii, CoPilot, and Navigon.

GPS works better with cellular and wifi networking turned on

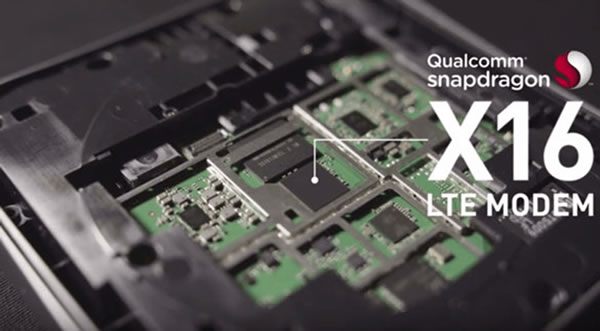

Since GPS uses radio waves from satellites to measure distances, it works best when the straight-line path between your device and the satellite isn’t impeded. Getting clear line-of-sight to the satellites above isn’t always possible in urban or tree-lined areas, and it’s impossible when you’re indoors. Luckily, there’s WPS (Wifi Positioning System), which is used to augment GPS by making use of the known locations of wifi base stations.

WPS works by using one or more databases containing the locations of wifi base stations based on their “fingerprints”, which are based on their SSIDs (their “names”) and MAC addresses (the unique identifier attached to every networked device) and their signal strength. These databases contain information on up to hundreds of millions of wifi base stations gathered from various sources. Quite often, these sources are everyone’s smartphones, which continually scan for wifi base stations and transmit their “fingerprints” and locations back to Apple, Google, or Microsoft, depending on your phone’s operating system. The keepers of these databases assure us that they’re protecting our privacy by anonymizing the data (take this statement with an appropriately-sized grain of salt).

There’s also aGPS — assisted GPS — which uses cellular networking to help your smartphone get the necessary information to more quickly acquire the satellite signals.

If you turn on cellular and wifi networking on your phone, it works in combination with GPS to provide you more accurate location information in more places, even in places where satellite signals aren’t as accessible. Wifi-only devices, such iPads without cellular data capability, use WPS to determine their location.

GPS is a power hog

Listening for an extended time to a handful of radio signals from satellites in space transmitting at a very slow rate — 50 bits (three characters on a web page) per second — eats battery power. Since your smartphone has to listen for these signals for extended periods, using GPS causes it to override its very clever and aggressive power-management system, which normally keeps power consumption to a minimum. Mapping applications, which are often used in conjunction with GPS, are processor-intensive, which increases the power drain.

Listening for an extended time to a handful of radio signals from satellites in space transmitting at a very slow rate — 50 bits (three characters on a web page) per second — eats battery power. Since your smartphone has to listen for these signals for extended periods, using GPS causes it to override its very clever and aggressive power-management system, which normally keeps power consumption to a minimum. Mapping applications, which are often used in conjunction with GPS, are processor-intensive, which increases the power drain.

When you’re using GPS on your phone while unplugged, use it sparingly. If you’re using GPS on your phone on a long drive, plug it in. You should keep a spare USB charging cable in your car, and if it doesn’t have a USB charging port, you should also keep a cigarette lighter USB power adapter (pictured above and to the right) handy.

Not-so-practical (but fun) considerations

On newer smartphones and operating systems, GPS stays on even in airplane mode

If you’re using iOS 8.3 or later (you can check by going to Settings → General → About and then look for Version) or a number of newer Android phones (including Samsung Galaxy S4 or later), the GPS remains on even in “Airplane Mode”.

If you’re using iOS 8.3 or later (you can check by going to Settings → General → About and then look for Version) or a number of newer Android phones (including Samsung Galaxy S4 or later), the GPS remains on even in “Airplane Mode”.

This is probably due to the fact that GPS is a receive-only technology; it doesn’t send out signals and therefore is less likely to interfere with the airplane’s electronics and navigation systems. Now that a number of flights have wifi, it’s now possible to see a map showing your current location in mid-flight. If you zoom in closely enough, you can see how quickly you’re zipping over city streets, which is an oddly mesmerizing experience.

GPS, Interstellar, and Einstein can turn you into a science genius

And finally, here’s an interesting fact concerning GPS that will give you some serious science cred at your social gathering. Let’s take a little detour by way of this scene from the 2014 film Interstellar:

In the scene pictured above, a team of astronauts led by Matthew McConaughey lands on a water-covered planet orbiting giant black hole. The black hole’s gravity is so strong that it slows down time in its general vicinity: for every hour they spend on the planet, seven years pass for outside observers.

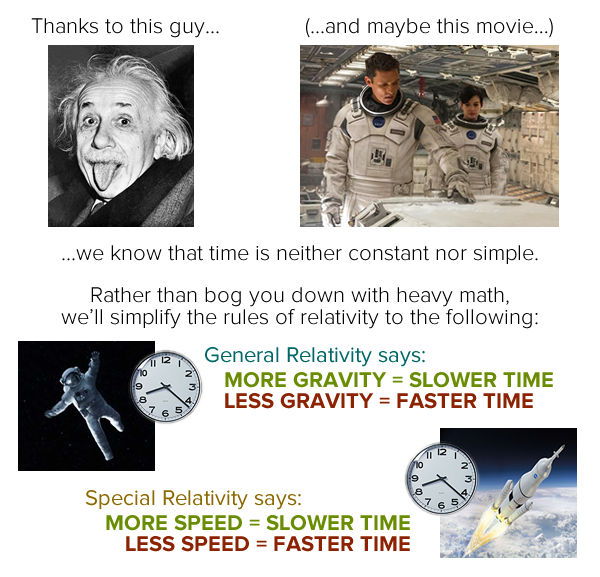

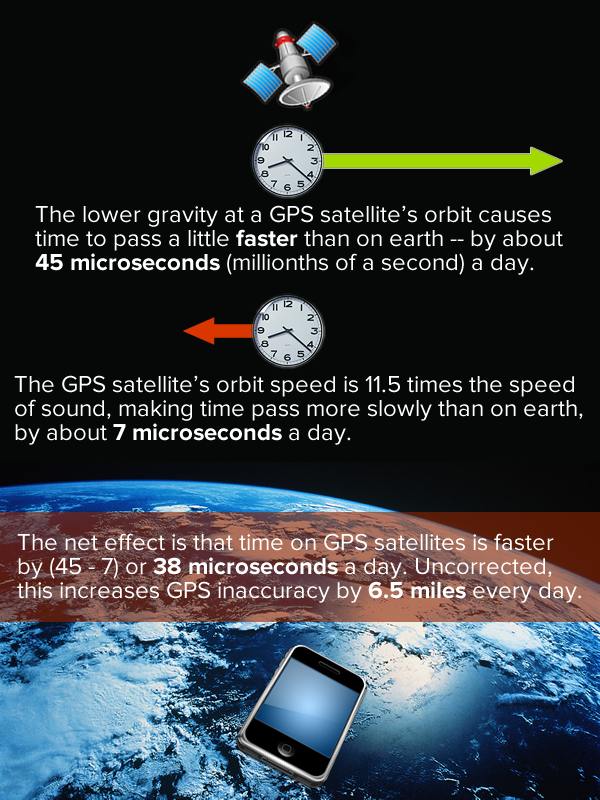

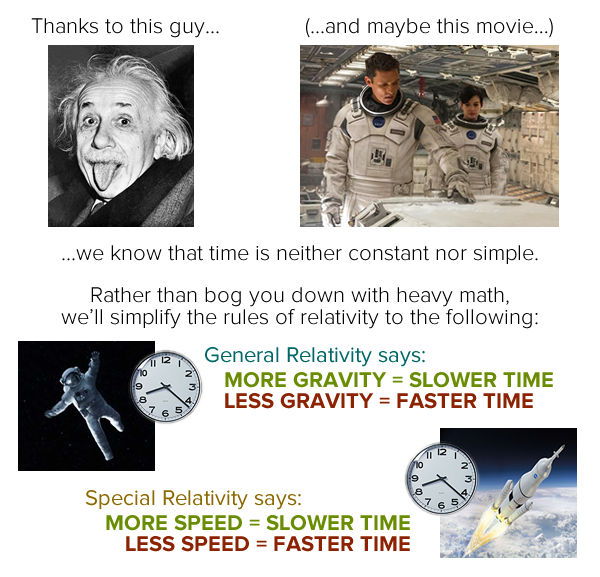

The idea of gravity slowing down time wasn’t something dreamed up by the film’s authors. Instead, it was dreamed up by Albert Einstein, when he came up with the Theory of Relativity. We’ll simply summarize Einstein’s greatest work with these two practical consequences:

While the effects of gravity on the GPS system aren’t anywhere as dramatic as in Interstellar, they’re still important enough to be accounted for.

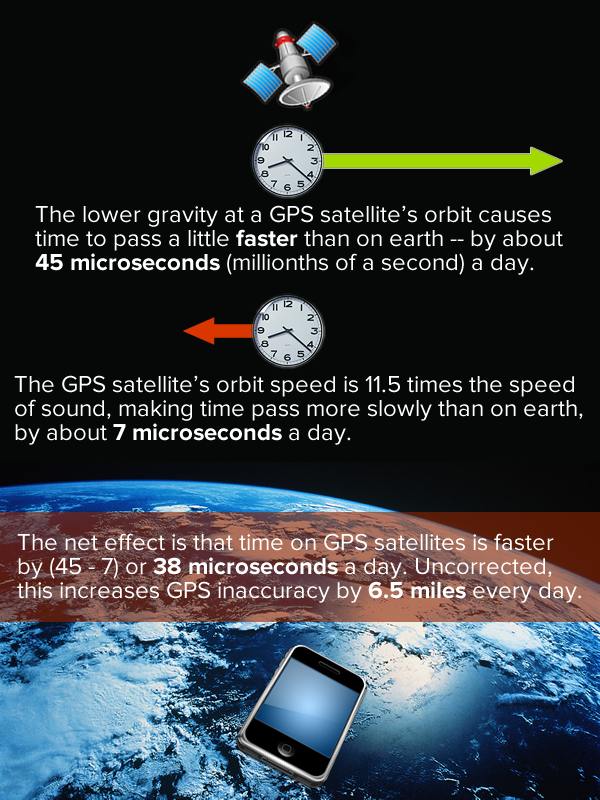

GPS satellites orbit the earth at an altitude of 12,500 miles (20,000 km), which means that the force of gravity on them is much lower. While in orbit, they move at 8,700 mph (14,000 km/h). Both these factors have measurable effects on time:

Since the GPS system relies on precise timekeeping, it introduces a time correction to account for the different speeds at which time moves on earth and on the satellites. The fact that this correction is needed is a practical, everyday application of Einstein’s Theory of Relativity and the seemingly sci-fi concept of warping time.

You may have noticed the cellular and internet networking aren’t mentioned in our explanation of how GPS works. Plain old GPS relies solely on the continuous, one-way signals broadcast by satellites and doesn’t need any cellular or internet data. Your smartphone doesn’t even send a request to a satellite to find its location, but simply listens to GPS’ always-on, always-available signals, in the same way you’d look for street signs and landmarks to get your bearings. As a result, using GPS by itself on your smartphone doesn’t eat into your data allotment or cost you any money…unless you’re a U.S. taxpayer.

You may have noticed the cellular and internet networking aren’t mentioned in our explanation of how GPS works. Plain old GPS relies solely on the continuous, one-way signals broadcast by satellites and doesn’t need any cellular or internet data. Your smartphone doesn’t even send a request to a satellite to find its location, but simply listens to GPS’ always-on, always-available signals, in the same way you’d look for street signs and landmarks to get your bearings. As a result, using GPS by itself on your smartphone doesn’t eat into your data allotment or cost you any money…unless you’re a U.S. taxpayer. The location data that you get from GPS — your latitude and longitude — are meaningless by themselves to most people. Usually, this data is paired with contextual information, such as a map from Google Maps, or a database of nearby locations from apps like Yelp, Starbucks, or GasBuddy. This contextual information comes from the internet, and if you’re getting it through your cellular connection rather than wifi, it’s using your allotted data, and you’re paying for it.

The location data that you get from GPS — your latitude and longitude — are meaningless by themselves to most people. Usually, this data is paired with contextual information, such as a map from Google Maps, or a database of nearby locations from apps like Yelp, Starbucks, or GasBuddy. This contextual information comes from the internet, and if you’re getting it through your cellular connection rather than wifi, it’s using your allotted data, and you’re paying for it.

Listening for an extended time to a handful of radio signals from satellites in space transmitting at a very slow rate — 50 bits (three characters on a web page) per second — eats battery power. Since your smartphone has to listen for these signals for extended periods, using GPS causes it to override its very clever and aggressive power-management system, which normally keeps power consumption to a minimum. Mapping applications, which are often used in conjunction with GPS, are processor-intensive, which increases the power drain.

Listening for an extended time to a handful of radio signals from satellites in space transmitting at a very slow rate — 50 bits (three characters on a web page) per second — eats battery power. Since your smartphone has to listen for these signals for extended periods, using GPS causes it to override its very clever and aggressive power-management system, which normally keeps power consumption to a minimum. Mapping applications, which are often used in conjunction with GPS, are processor-intensive, which increases the power drain.