It’s always a treat to see one of Dr. Venkat Subramaniam’s presentations, and Monday evening’s session, Identifying and fixing Issues in Code using AI-based tools, was no exception!

On behalf of the Tampa Bay Artificial Intelligence Meetup, Anitra and I would like to thank Ammar Yusuf, Tampa Java User Group, and Tampa Devs for inviting us to participate in this meetup, and to thank Venkat for an excellent lecture.

Part 1: What AI actually Is (and isn’t)

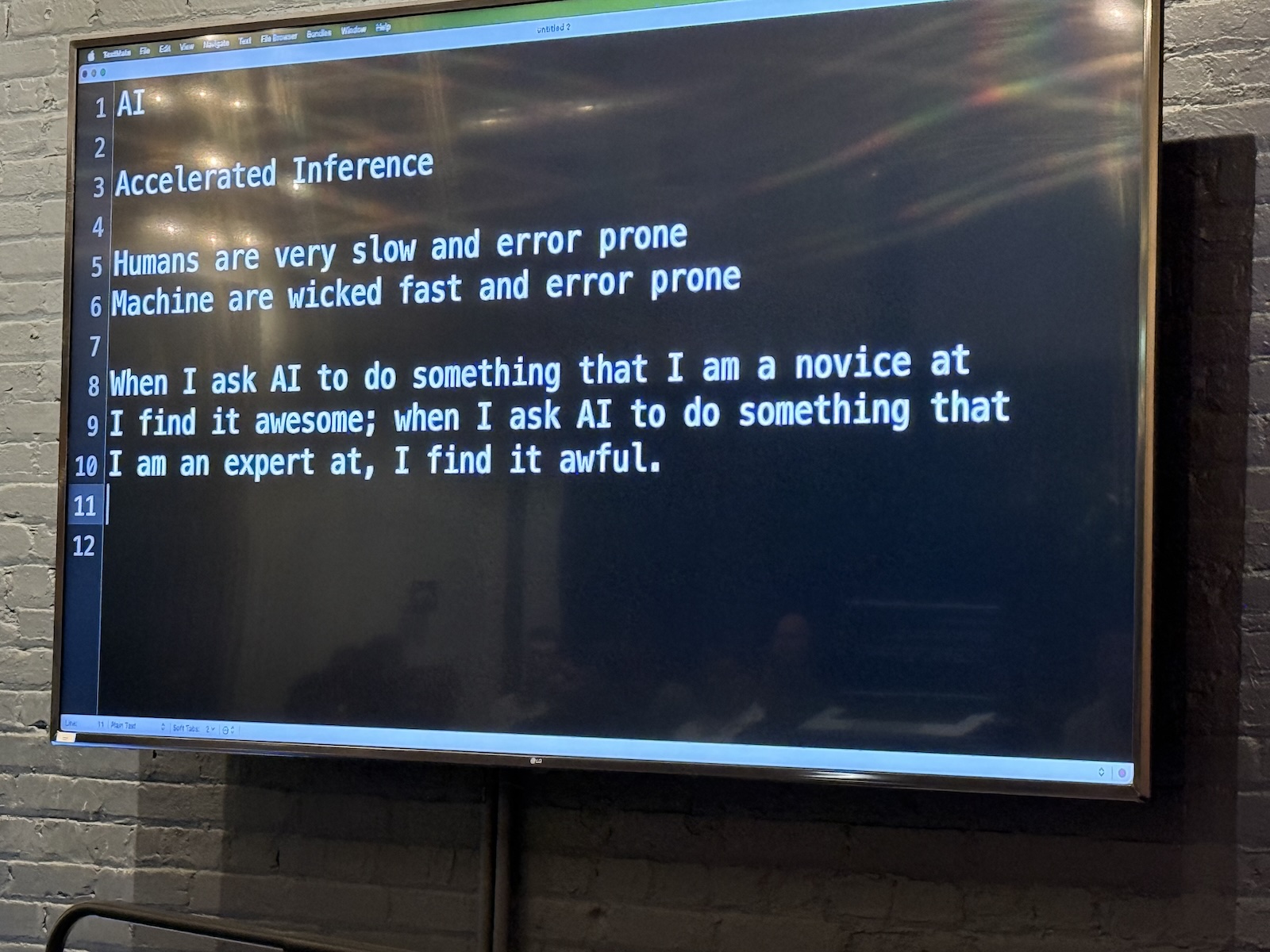

Think of AI as “Accelerated Inference”

- The reality check: The term “Artificial Intelligence” is misleading. It suggests that an application has sentience or wisdom. Venkat suggests a more accurate definition for AI: Accelerated Inference.

- Inference vs. intelligence:

- If you see a purple chair and then another purple chair, you infer that chairs are purple. That isn’t necessarily true, but it is a logical conclusion based on available data.

- AI does this on a massive scale. It doesn’t “know” the answer; it infers the most statistically probable answer based on the massive volume of data it was fed.

- Speed vs. accuracy: Machines are “wicked fast,” but they are also error-prone. Humans are slow and error-prone. AI allows us to make mistakes at a much higher velocity if we aren’t careful.

Karma

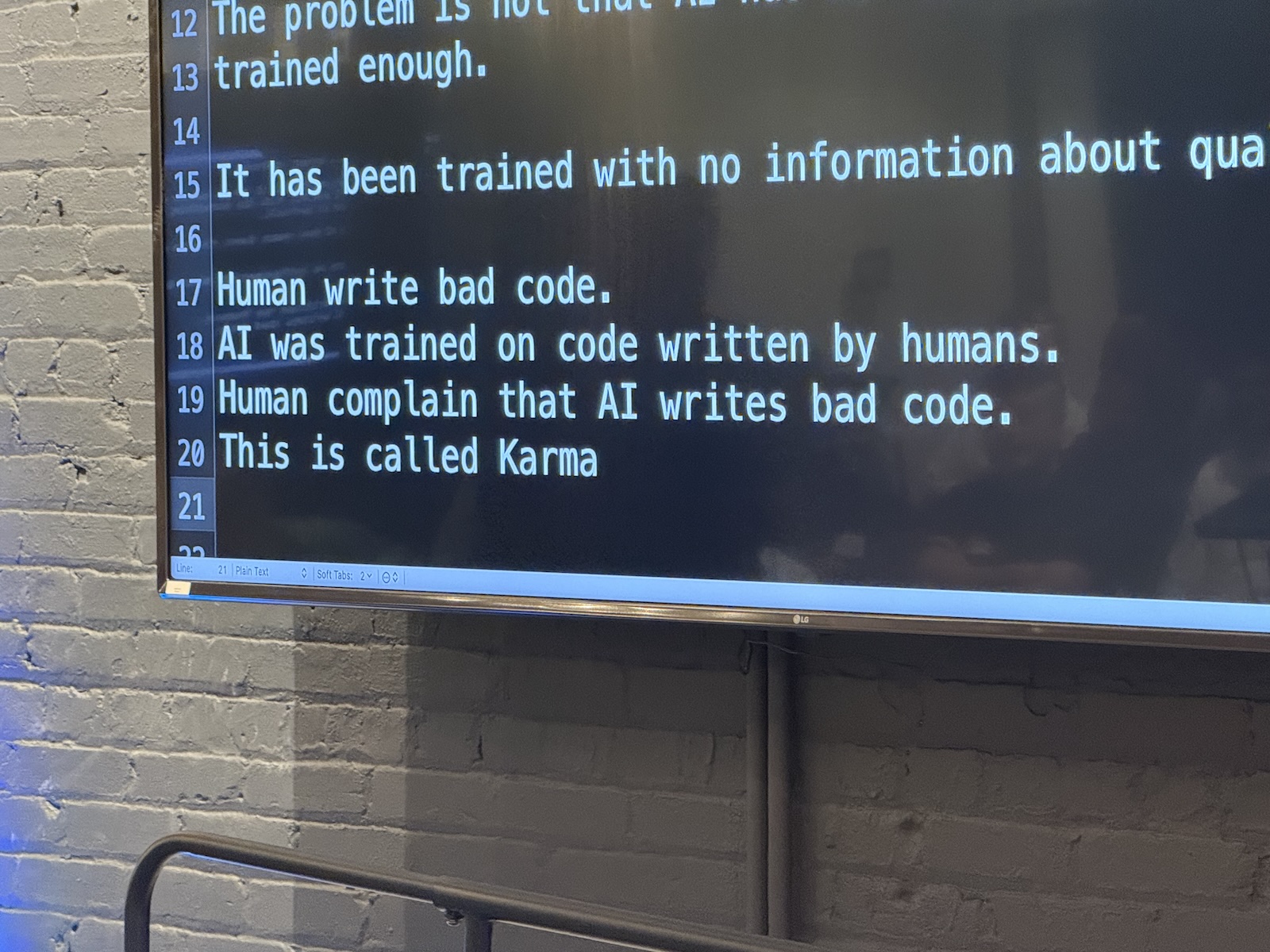

- Garbage in, garbage out: AI models are trained on billions of lines of code, most of it written by humans (at least for now).

- The problem: Humans write bugs. We write security vulnerabilities. We write bad variable names.

- The consequence: Because AI learns from human code, it learns our bad habits. Venkat says this is karma. When we complain about AI writing bad code, we’re really complaining about our own collective history of programming mistakes coming back to haunt us.

- The takeaway: Don’t assume AI output is “production-ready.” Treat AI-generated code with the same skepticism you would treat code copied from a random forum post in 2010.

The “novice vs. expert ” paradox

Venkat described a specific phenomenon regarding how we perceive AI’s competence:

- The novice view: When you ask an AI to do something you know nothing about (e.g., writing a poem in a language you don’t speak), the result looks amazing. You find it awesome because you lack the expertise to judge it.

- The expert view: When you ask AI to do something you are an expert in (e.g., writing high-performance Java code), you often find the result “awful.” You can spot the subtle bugs, the global variables, and the inefficiencies immediately.

- The danger zone: As a developer, you are often in the middle. You know enough to be dangerous. Be careful not to be dazzled by the “novice view” when generating code for a new framework or language.

Part 2: Strategies for using AI effectively

1. Use AI for ideas instead of solutions

- Don’t ask for the answer immediately. If you treat AI as a maker of solutions, you bypass the critical thinking process required to be a good engineer.

- Ask for approaches. Instead of “Write this function,” ask: “I need to solve X problem. What are three different design patterns I could use?”

- Love the weirdness: AI is great at throwing out random, sometimes hallucinated ideas. Use these as inspirations or starting points for brainstorming. “Accept weird ideas, but reject strange solutions,” Venkat said.

2. Managing cognitive load

- The human limit: We struggle to keep massive amounts of context in our heads. We get tired. We get “analysis paralysis.”

- AI’s strong suit: AI doesn’t get tired. It can read a 7,000-line legacy function with terrible variable names and not get a headache or confused.

- The “Translator” technique:

- Venkat used the analogy of translating a foreign language into your “mother tongue” to understand it emotionally and logically.

- Try this: Paste a complex, confusing block of legacy code into an AI tool and ask, “Explain this to me in plain English.” This helps you understand intent without getting bogged down in syntax.

3. The Δt (“delta t”) approach

- Don’t “one-shot” it: Just as numerical analysis (calculus) requires taking small steps (Δt) to get an accurate curve, working with AI requires small iterations.

- Workflow:

- Present the AI with the problem and ask it for possible approaches.

- Review its replies. Chances are that at least some of them (or maybe all of them) will be wrong, buggy, or not the answer you’re looking for.

- Don’t give up. Instead, provide feedback: “This code isn’t thread-safe,” or “This variable is null.”

- The AI will often correct itself. This back-and-forth “dance” is where the actual development happens.

Part 3: Code examples

Venkat demonstrated several scenarios where code looked correct but had problems that weren’t immediately apparent, and showed how AI helped (or didn’t).

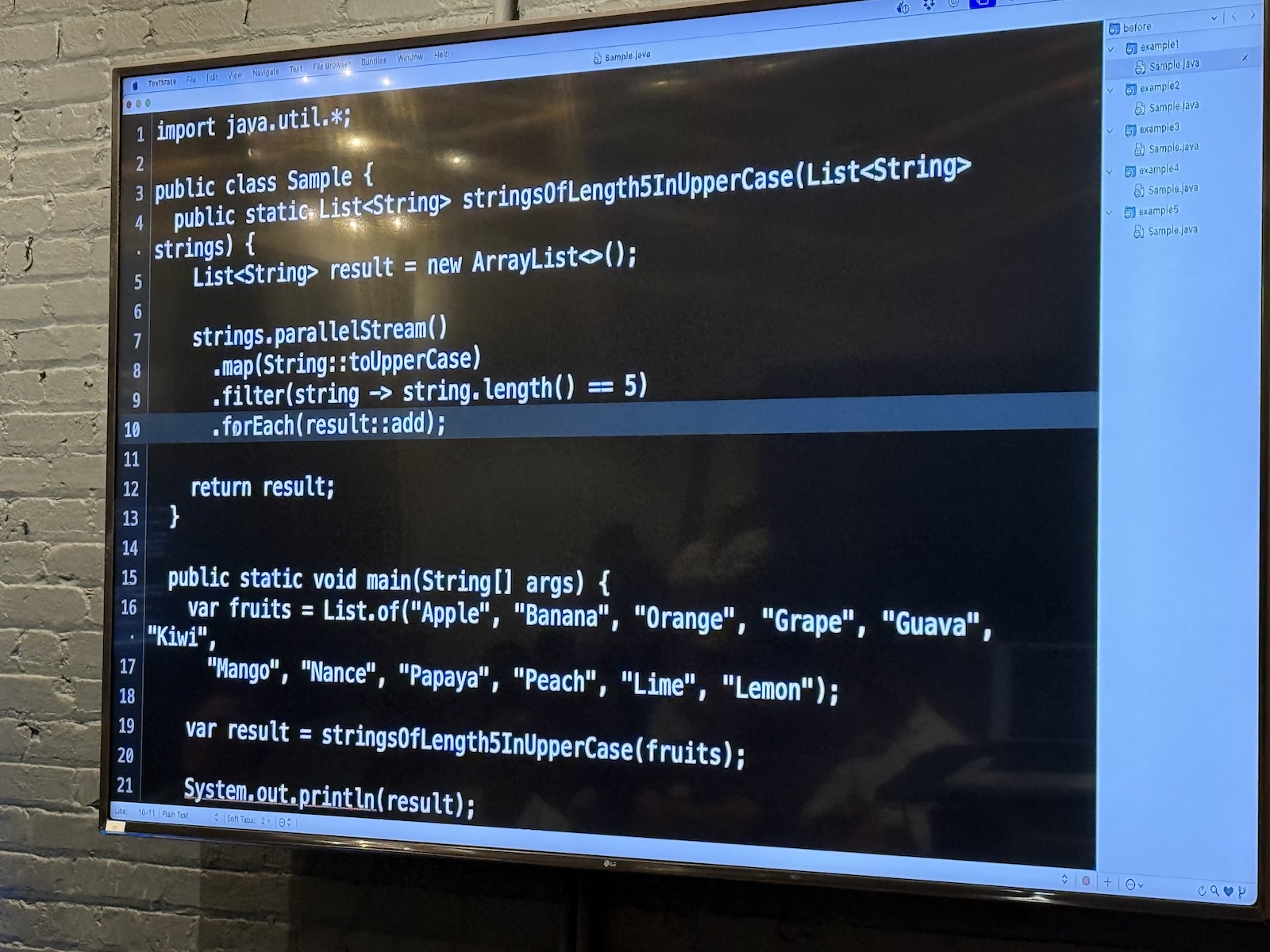

Case study: Fruit

The first case study was a version of a problem presented to Venkat by a client. He couldn’t present the actual code without violating the client NDA, so he presented a simplified version that still captured the general idea of the problem with the code.

Here’s the first version of the code:

// Java

import java.util.*;

public class Sample {

public static List stringsOfLength5InUpperCase(List strings) {

List result = new ArrayList<>();

strings.stream()

.map(String::toUpperCase)

.filter(string -> string.length() == 5)

.forEach(result::add);

return result;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

var fruits = List.of("Apple", "Banana", "Orange", "Grape", "Guava", "Kiwi",

"Mango", "Nance", "Papaya", "Peach", "Lime", "Lemon");

var result = stringsOfLength5InUpperCase(fruits);

System.out.println(result);

}

}

This version of the code works as expected, printing the 7 fruit names in the list that are 5 characters long.

Right now, it’s single-threaded, and it could be so much more efficient! A quick change from .stream() to .parallelStream()should do the trick, and the resulting code becomes

// Java

import java.util.*;

public class Sample {

public static List stringsOfLength5InUpperCase(List strings) {

List result = new ArrayList<>();

// Here's the change

strings.parallelStream()

.map(String::toUpperCase)

.filter(string -> string.length() == 5)

.forEach(result::add);

return result;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

var fruits = List.of("Apple", "Banana", "Orange", "Grape", "Guava", "Kiwi",

"Mango", "Nance", "Papaya", "Peach", "Lime", "Lemon");

var result = stringsOfLength5InUpperCase(fruits);

System.out.println(result);

}

}

The code appears to work — until you run it several times and notice that it will occasionally produce a list of less than 7 fruit names.

Why did this happen? Because Java’sArrayList isn’t thread-safe, and writing to a shared variable from inside a parallel stream causes race conditions. But this is the kind of bug that’s hard to spot.

Venkat fed the code to Claude and asked what was wrong with it, and after a couple of tries (because AI responses aren’t consistent), it identified the problem: creating a side effect in a stream and relying on its value. It suggested using a collector like toList() to capture the the 5-character fruit names; it’s thread-safe.

Claude also suggested applying the filter before converting the list values to uppercase, so as not to perform work on values that would be filtered out.

The takeaway: AI is excellent at spotting errors that we humans often miss because we’re so focused on the business logic.

Case study: Parameters

I didn’t get a photo of this code example, but it featured a function that looked like this:

public String doSomething(String someValue) {

// Some code here

someValue = doSomethisElse(someValue)

// More code here

}

I’m particularly proud of the fact that I spotted the mistake was the first one to point it out: mutating a parameter.

Venkat fed the code to Claude, and it dutifully reported the same error.

It was easy for me to spot such an error in a lone function. But spotting errors like this in an entire project of files? I’d rather let AI do that.

Case study: Currency converter

I didn’t get a photo of this one, but it featured base class CurrencyConverter with a method convert(float amount). A subclass NokConverter attempted to override it to handle Norwegian Krone.

The problem was that NokConverter’s conversion method’s signature was convert(int amount), which meant that it was overloaded instead of overridden. As a result, polymorphism was lost, and the client code ends up calling the base class method instead of the subclass method. But that’s pretty easy to miss — after all, the code appears to work properly.

A quick check with the AI pointed out that the method was not actually overriding, and it also suggested adding the @Override annotation, which is meant to prevent this kind of subtle error.

Remember: don’t just let AI fix it; understand why the fix works. In this case, it was about strictly enforcing contract hierarchy.

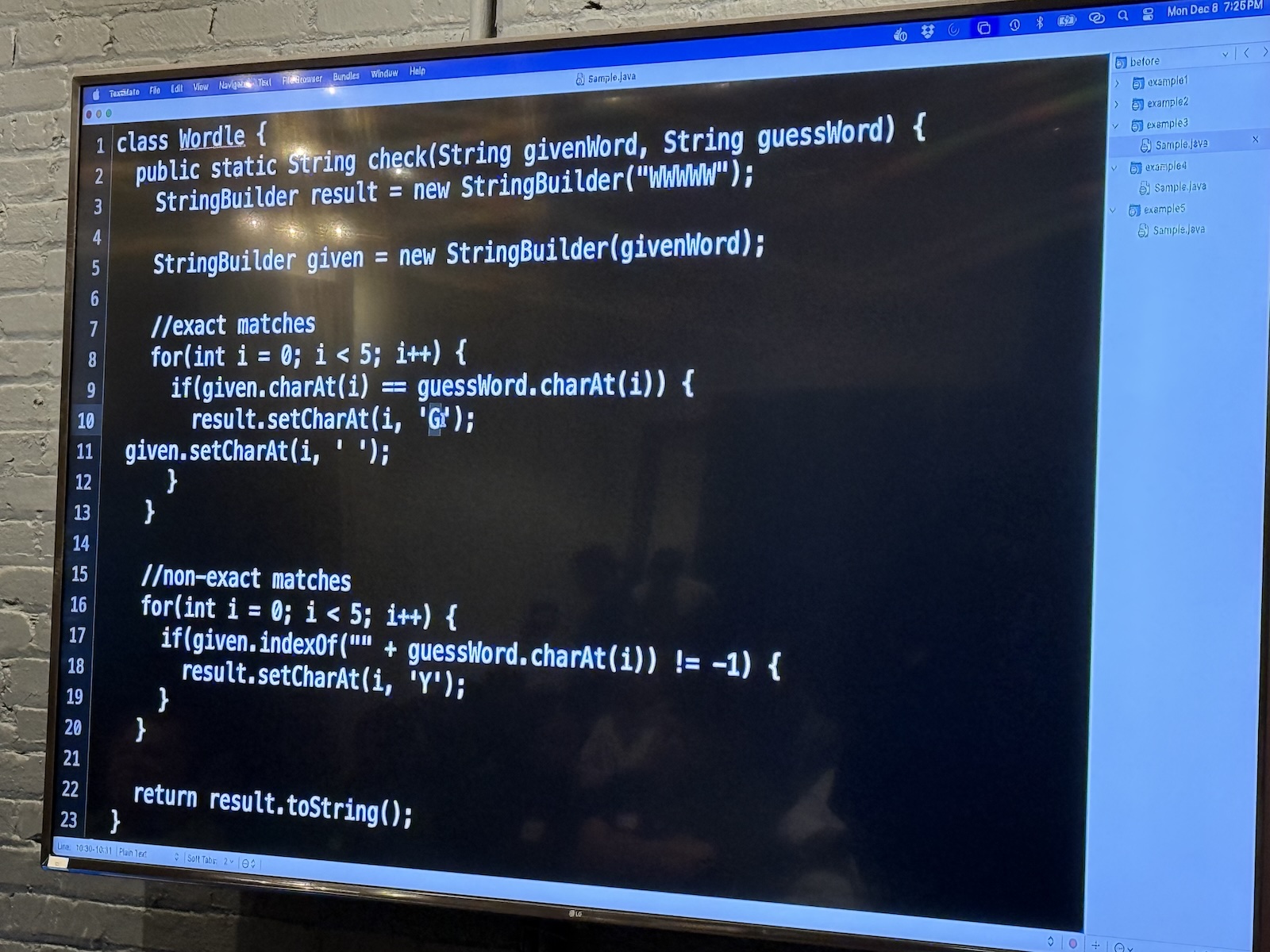

Case study: Wordle

Venkat asked Claude to write a Wordle clone, and it did so in seconds.

But: the logic regarding how yellow/green squares were calculated was slightly off in edge cases.

AI sometimes implements logic that looks like the rules but fails on specific boundary conditions. It’s a good idea to write unit tests for AI-generated logic. Never trust that the algorithmic logic is sound just because the syntax is correct.

Part 4: The “Testing” Gap

Missing test suites

- Venkat noted a disturbing trend: he sees very few test cases accompanying AI-generated code.

- Developers tend to generate the solution and manually verify it once (“It works on my machine”), then ship it.

- The Risk: AI code is brittle. If you ask it to refactor later, it might break the logic. Without a regression test suite (which the AI didn’t write for you), you won’t know.

How to use AI for testing

- Invert the flow! Instead of asking AI to write the code, write the code yourself (or design it), and ask AI to:

- “Generate 10 unit tests for this function, including edge cases.”

- “Find input values that would cause this function to crash.”

- AI is often better at playing “Devil’s Advocate” (breaking code) than being the Architect (building code).

Part 5: Takeaways

Job security in the age of AI

- The Fear: “Will I lose my job to AI?”

- The Reality: You will not lose your job to AI. You will lose your job to another programmer who knows how to use AI better than you do.

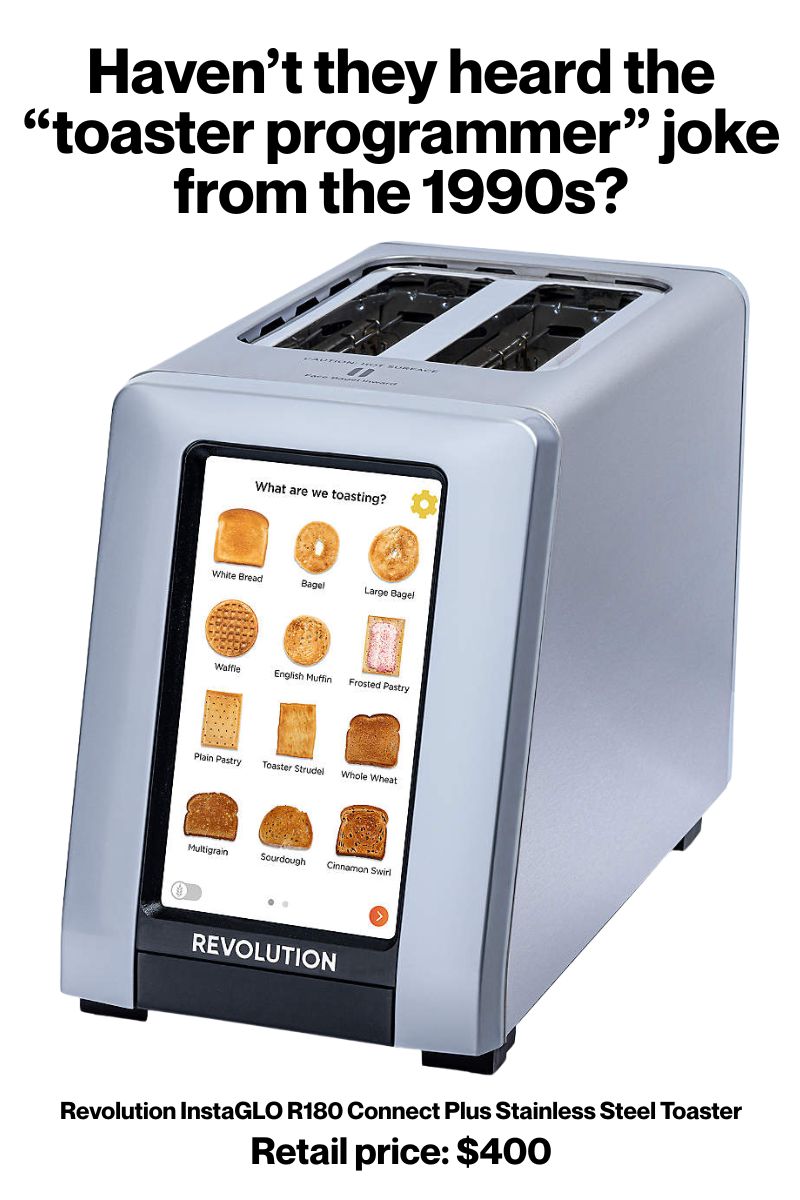

- The “Code Monkey” extinction: If your primary skill is just typing syntax (converting a thought into Java/Python syntax), you are replaceable. AI does that better.

- The value-add: Your value is now as a problem solver and solution reviewer. You’re paid to understand the business requirements and ensure the machine code actually meets them.

Adaptation is key!

- Venkat used a quote commonly attributed to Charles Darwin (see here for more): “It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is most adaptable to change.”

- Action Plan:

- Don’t fight the tool

- Don’t blindly trust the tool

- Learn to verify the tool

- Shift your focus from “How do we write a loop?” to “Why are we writing this loop?”

Empathy and code review

- When AI generates bad code, we analyze it dispassionately. When humans write bad code, we get angry or judgmental.

- The Shift: We need to extend the “AI Review” mindset to human code reviews. Be objective. Find the fault in the logic, not the person.

- AI has shown us that everyone (including the machine trained on everyone’s code) writes bad code. It’s the universal developer experience.