File under “Funny because it’s true”

The 2022 edition of Tampa Code Camp (a.k.a. #TampaCC) took place on Saturday, October 8th, and Anitra and I were there to give presentations, attend presentations, catch up with some old friends and colleagues, and make some new ones.

Organized by Kate and Greg Leonardo, Tampa Code Camp has been a local tech tradition for years. While it’s been the de facto local conference for people building on Microsoft/.NET/Azure technologies, it goes beyond that to include Open Source, data science, AI/ML, and soft skills sessions. (My own first presentation at Tampa Code Camp was in 2016, when I presented an introduction to React.)

Tampa Code Camp 2022 took place at Keiser University Tampa, who’ve been gracious enough to make their space available a venue for tech events with 100 people or more for the past few years, including Tampa Code Camp and the BarCamp Tampa Bay unconference. They have a spacious lobby that makes for a great reception/registration and sponsor booth hall, a good-sized auditorium for opening keynotes and lunches (made even better by a patio area), and classrooms of all sizes to accommodate all sorts of talks, each one with a reliable audiovisual setup for presenters.

I was so busy either prepping for my presentation, presenting, or just chatting with people that I took all of two photos. Luckily, a number of people who were there took some and posted them on Twitter; I’ve shared them below and they’re linked to their source.

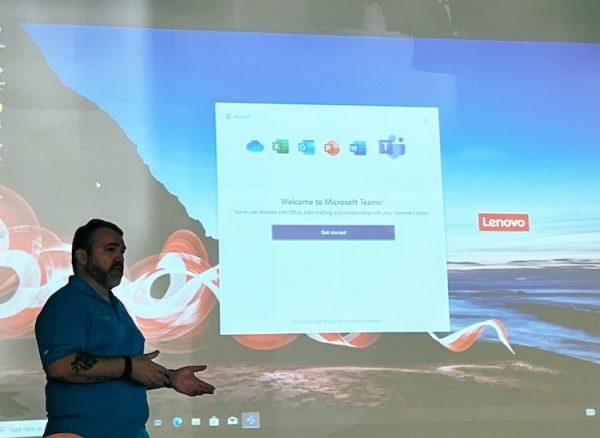

Here’s the opening keynote, given by co-organizer Greg Leonardo, who talked about the unexpected (and often untold) consequences of moving your back end from on-premises to the cloud, often known as the “lift-and-shift.” There are good reasons to move to the cloud, but the rationale (or more accurately, sales pitch) of cost savings has been oversold — in fact, there’s often a cost increase.

Another key message from the opening keynote: running things on the cloud isn’t simply a matter of “our old stuff, but now on someone else’s servers.” It often requires a different approach and some re-thinking about how you do implementation and architecture. Some of the things you did when your servers were on-prem can be much worse when moved to the cloud. Watch out for these “onions in the varnish!”

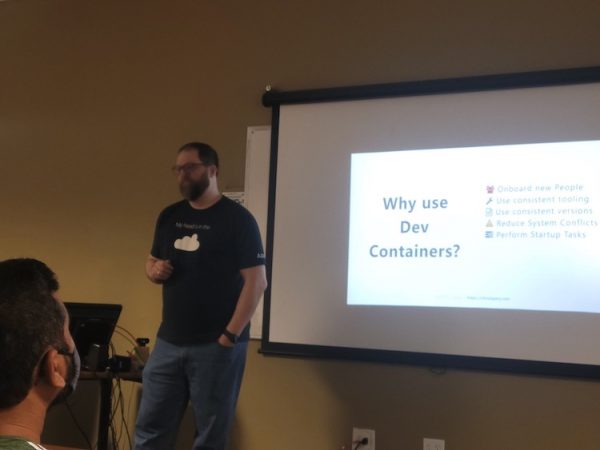

Here’s Chris Ayers, Senior Customer Engineer at Microsoft, giving his presentation, Dev Containers in VS Code, a handy feature that gives you a Docker container as a development environment:

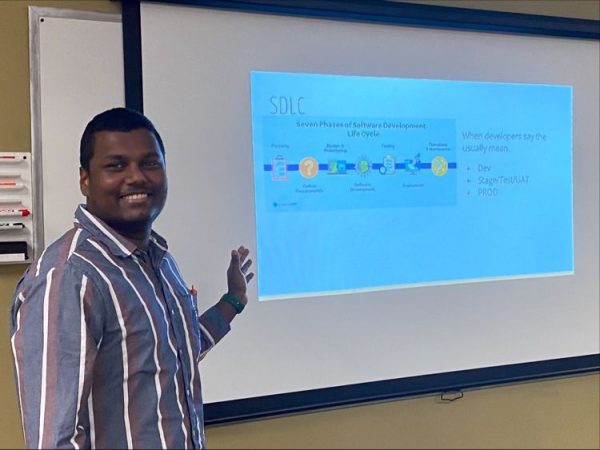

We caught Sam Kasimalla’s session, titled IT life cycle and a bit of devops – Industry notes, which presented a solid overview aimed at people who are just entering (or pivoting to) our industry:

After Sam’s presentation, I raced to my room to give my talk, Build cross-platform visual novels, simulations, and games with Ren’Py, where I walked the group through the development of a “Choose Your Own Adventure”-style infosec training manual and a turn-based “Florida Man” RPG-style combat game:

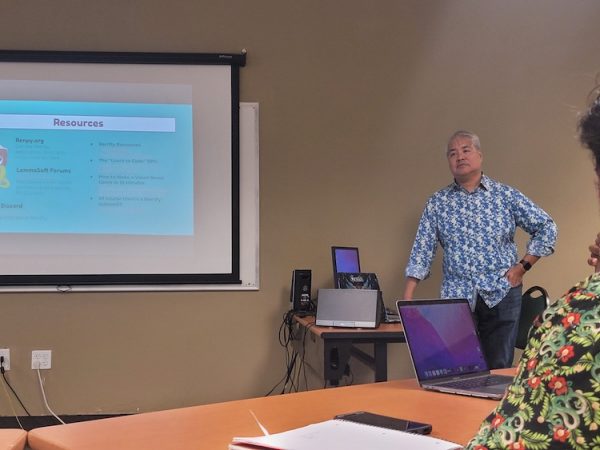

While I was talking about Ren’Py development, Art Garcia was a couple of rooms over, giving his presentation, Azure DevOps APIs: Things you can do with the APIs, where he covered ways to do things that you can’t do using the Azure DevOps UI, but can if you use PowerShell, the APIs, and some tricks that aren’t well-documented.

I’d like to thank Tampa Code Camp for not just providing a free lunch (and breakfast coffee and donuts — much apprecated!), but for estimating high in order to ensure that everybody could get a free lunch. It’s little touches like these that add to these events.

I don’t have a photo for Russ Fustino’s session, Web3 – Blockchain Myths for Developers, but we attended that one. Russ has been a local fixture on the tech scene ever since I’ve lived here (nearly a decade!) and we definitely want to catch him. His brother Gary (also a tech scene regular) recorded video of the session, so it should be online soon.

In the same time slot, Chris Cognetta gave his Power Apps in the Real World talk, where he covered Power Platform and Power Apps:

After that, Anitra Pavka gave her talk, Manage your manager for fun, profit, and career success, which covered the valuable, vital, yet often-overlooked topic of working with the one person who has control of half your weekday waking life:

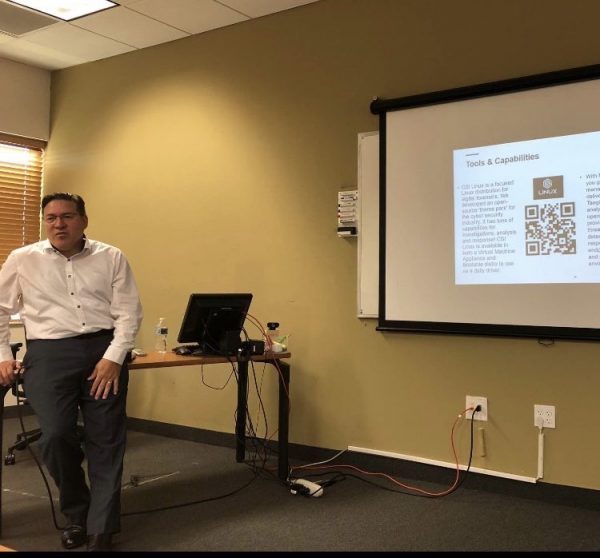

At the end of the day came Joey Hernandez’ Cyber Incident Response Exercise – From Tech to Exec talk — an excellent topic, because so many companies get this wrong for a multitude of reasons. He talked about TTXs — tabletop exercises, which in cybersecurity are preparedness exercises where you go through the steps of a simulated security incident.

Also at the end of the day: Jared Rhodes gave his fourth talk of Tampa Code Camp 2022: Homelab – Private Cloud on a Budget! I’ve been meaning to give homelabs a look.

Jared deserves a prize for being the busiest presenter at Tampa Code Camp 2022, because he also gave these talks:

And he came here from Atlanta to give his talks. I think the Azure team should at least send him some of their nicer swag for doing all this work on their behalf.

Events like this don’t happen without sponsors. First, thanks to Keiser University Tampa for providing a venue!

Events like this go even better when the presenters get a chance to catch up beforehand, hence the long-standing tradition of a speaker dinner. Once again, it happened at the always-reliable, always-fun Tampa Joe’s. Thanks for the food and drinks!

Starbucks was the coffee sponsor. Free coffee? Bless you.

Thanks to Pomeroy for helping make Tampa Code Camp 2022 happen, and for providing one of the raffle prizes: a Meta Quest 2 VR rig!

Pomeroy also provided some swag that I needed:

Algorand also had a table, and when Russ wasn’t giving his Algorand presentation, he was at the Algorand table, and he answered a number of my questions and hooked us up with nice T-shirts. Thanks, Algorand!

And finally, I’d like to thank Webonology — which is also Greg’s company — for being a sponsor and contributing the grand prize, an Xbox Series X!

Please check out these sponsors. They do great work, they supported this great event, and they’re helping to build the Tampa Bay tech scene!

What makes a tech scene?

In the end, it boils down to a single factor: techies who take part in building a tech community. There are cities out there with sizable populations of techies that aren’t tech hubs — these are places without people who help build a tech community. There are also smaller places with smaller numbers of techies but have a vibrant tech scene, and these are the places with a handful of active organizers and people who show up for tech events.

Among these active organizers are Kate and Greg Leonardo, who’ve been consistently stepping up and doing the (often, but not always) thankless work of putting together events like Tampa Code Camp and upcoming events for 2023. Thank you, Kate and Greg, for everything you do for the Tampa Tech Scene!

TampaCC, Tampa’s FREE annual code camp, where you can sharpen your software development skills, is happening this Saturday, October 8th in Tampa at Keiser University. This is your chance to learn something new and get to know the Tampa tech community!

I’ll say it again: it’s FREE to attend! Register here to let them know that you’re attending.

Here’s the schedule. Click the presentation names to find out more:

Keiser University is a great venue with lots of space for several simultaneous sessions and has been the gracious host of so many Tampa Bay tech events.

And of course, credit has to go to TampaCC’s long-time organizers, Kate and Greg Leonardo — thanks so much for putting this together! I’m looking forward to returning to TampaCC (and presenting, too!)

Want to attend (and remember, it’s FREE!)? Register here and we’ll see you on Saturday!

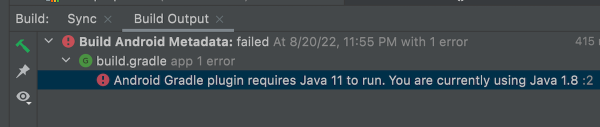

Maybe you’ve run into this Android Studio problem lately. You’ve created a brand new project, and when you run it — even if you haven’t made any changes — you get the dreaded Android Gradle plugin requires Java 11 to run error:

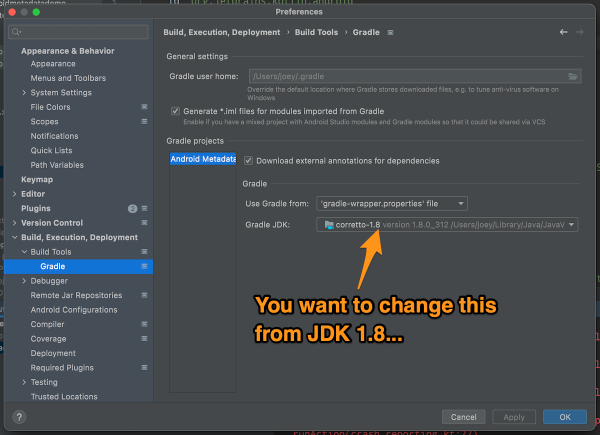

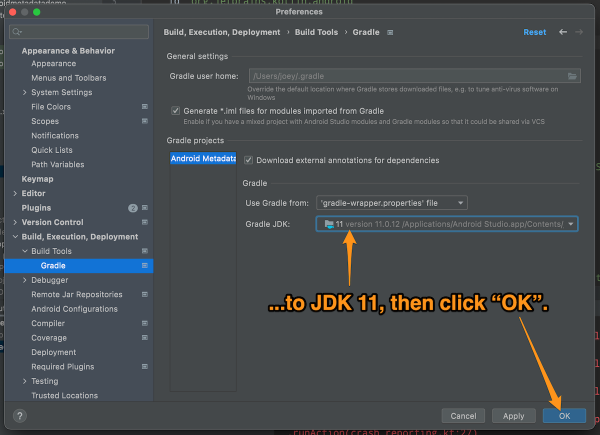

Here’s the “quick and dirty” fix. It assumes that you already have JDK 11 installed.

Once the Settings or Preferences window is open, select Build, Execution, Deployment → Build Tools → Gradle from the menu on the left side.

You can change the JDK that Gradle uses in the Gradle projects section’s Gradle JDK menu. Changing the current selection from JDK 1.8 to JDK 11 works for me:

The Android Studio on my Windows machine already defaults Gradle to JDK 11, but on my Mac, it’s still insisting on JDK 1.8. I’m sure there’s some config file floating around somewhere that I need to edit — does anyone know which one? — but in the meantime, I’m using the quick and dirty fix.

Yesterday was Evening 3 of the 10-evening “Learn Python” class that I’m teaching on behalf of Computer Coach, a tech training center here in Tampa. It started last Wednesday and takes place online every Monday and Wednesday from 6:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m.. There are 15 students in the class.

So far, the class is going well. In fact, I’m rather impressed. Even though some of them have only a little programming experience and others have none, they’re learning at a great pace, and better still, they’re cleverly applying what they’re learning, and they’re not afraid to ask questions and experiment.

For example, there’s the Fizzbuzz exercise. It’s where the challenge is to a program that counts from 1 to 100 and prints out the current number as it does this, while following these rules:

Not only did they figure out how to make it work — not bad for evening 2! — but some of them started add their own ideas to the application. One said “I’m tweaking the program so that you can enter what numbers get turned into ‘fizz’ and ‘buzz’ instead of just 3 and 5.” And those modifications worked.

While covering if for comparing numbers, another student asked “Is there some way where I can compare a number to see if it’s part of a group of different numbers?” This led me to introduce lists and the in operator a little early, but it was a sign that one of them was already trying to come up with ways to apply a concept they’d just learned minutes before.

Last night, while I was demonstrating some list methods, yet another student asked “How do I pop an item from one list and then add it to another?” Again, that’s something someone does only when they grasp a new concept and start thinking up applications for it.

I just have to say this: I’m very impressed with this Python class.

Here’s a quick summary of the course:

You’ll need the following to participate in the course:

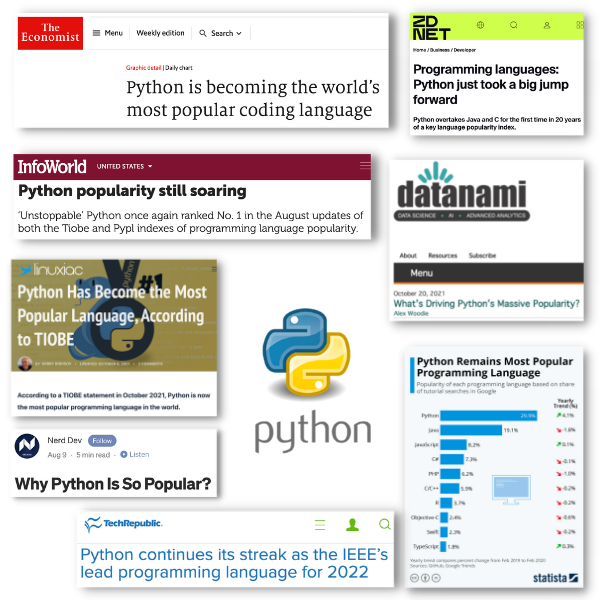

All you have to do is look at the current developer surveys and tech news headlines to know that right now, Python is having its “moment”:

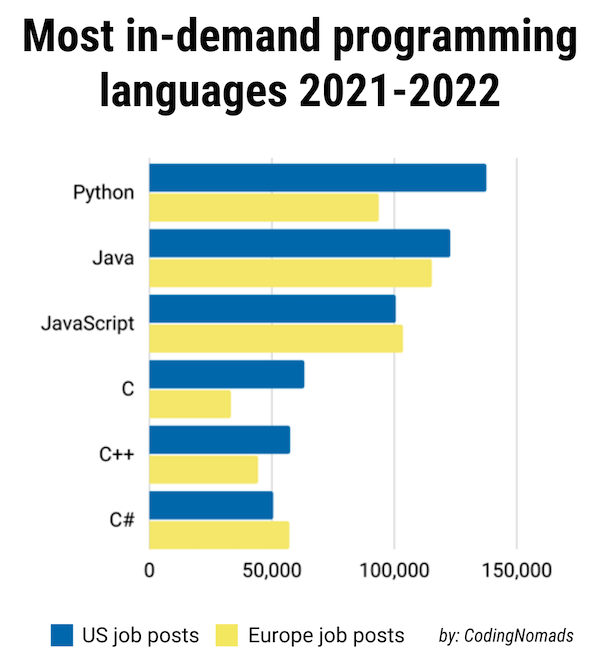

CodingNomads, a coding school in California, looked at thousands of job postings in North America and Europe and declared Python as the most in-demand coding language for 2022.

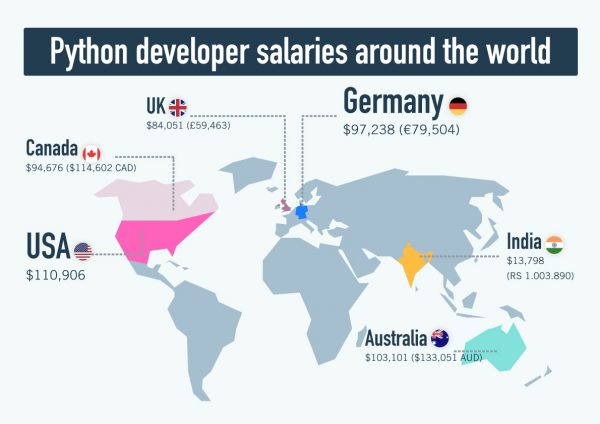

As for salaries…

…you can say that the pay is decent. Pair Python with another tech skill (for instance, JavaScript) or a people skill (say, managing developers), and you can make even more.

This is the course schedule for Learn Python. It’s flexible — if there’s a need spend more time on a specific topic, we’ll do that. The point isn’t to cover every topic on the list; it’s to give you the necessary grounding in Python and programming to continue after the course is over!

Sessions will take place via Zoom, which means that you can take the course from wherever you happen to be. There will be ten sessions, and each will run from 6:00 p.m. to 10:00 p.m., with ten-minute breaks at the end of the first, second, and third hour.

This is not a passive course! This isn’t the kind of course where the instructor lectures over slides while you take notes (or pretend to take notes while surfing the web or checking your social media feeds). In this course, you’ll follow along as I write code on my screen. You’ll actively take part in the learning process, entering code, experimenting, making mistakes, correcting those mistakes, and producing working applications. You will learn by doing. At the end of each session, you’ll have a collection of little Python programs that you wrote, and which you can use as the basis for your own work.

The course will start at the most basic level by walking you through the process of downloading and installing the necessary tools to start Python programming. From there, you’ll learn the building blocks of the Python programming language:

Better still, you’ll learn how to think like a programmer. You’ll learn how to look at a goal and learn how you could write a program to meet it, and how that program could be improved or enhanced. You’ll learn skills that will serve you well as you take up other programming languages, and even learn a little bit about the inner workings of computers, operating systems, and the internet.

We’ll build as many applications as we can, based on your suggestions or needs. These include (and aren’t limited to):

Once again, you’ll want to contact Computer Coach’s Kasandra Perez at Contact Kasandra Perez at kasandra@computercoach.com or (813)-254-6459 to find out more about the course or register.