Yes, you can run Visual Studio Code on Raspberry Pi!

You’ve got many options for editing code or other plain text files on your Raspberry Pi. It is, after all, a Linux machine, and you’ve got all the classic command-line editors — vim, emacs, and…

And the windows-and-mouse-based Geany (text editor) and Thonny (beginner-friendly Python IDE) come along with even the bare-bones version of the Raspberry Pi OS setup.

But if you’re like about half the developers who answered the 2019 Stack Overflow survey, your “home” editor is Visual Studio Code. And yes, you can run Visual Studio Code on Raspberry Pi.

How to install Visual Studio Code on Raspberry Pi

If you go to Visual Studio Code’s “downloads” page, you’ll see this:

For the Raspberry Pi, you want to download the Debian package for systems with ARM processors (click on the ARM button in the .deb row).

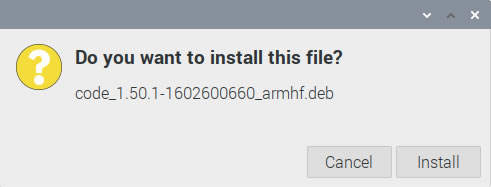

Once downloaded, go to your Downloads directory and double-click on the the .deb file you just downloaded. You’ll see greeted with this dialog box:

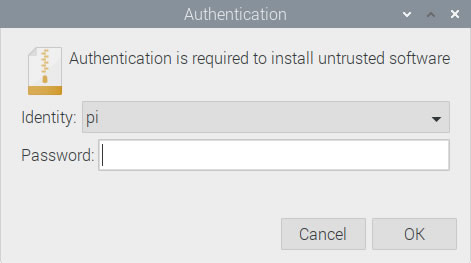

Click the Install button. You’ll be presented with another dialog box, this time asking for your user password, since it’s required when installing new applications:

Enter the password you use to log into the Raspberry Pi into the Password field and click OK.

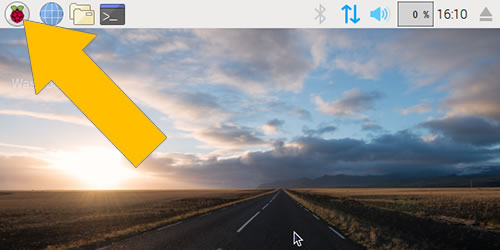

Visual Studio Code will be installed on your Pi. Once the process is done, you can launch it by clicking on the Start Menu (the raspberry icon in the upper left-hand corner)…

…and in the menu that appears, select the Programming menu. A sub-menu will appear, and one of the items will be Visual Studio Code. Click that and…

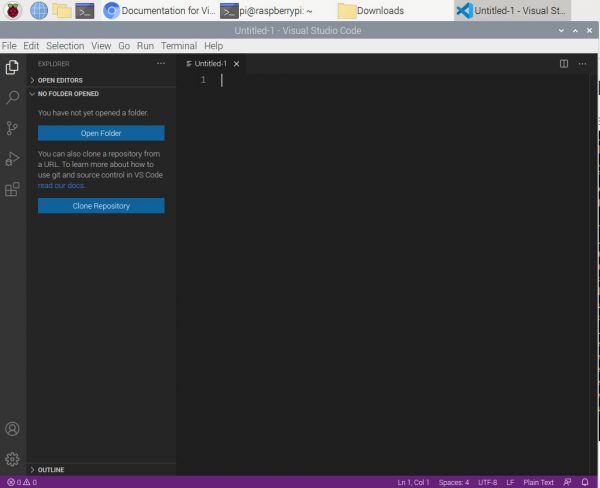

You’ll be in the Visual Studio Code that you know and love from Windows, macOS, and Linux! And yes, all the plugins that you’ve come to depend on will be available.

Go forth and code!