Next Tuesday, April 2nd at 6:15 p.m. Central / 7:15 p.m. Eastern / 23:15 UTC, I’ll lead an online introductory session for people who to dive into AI titled AI: How to Jump In Right Away.

ℹ️ Click here to register for the presentation.

My session is part of Austin Forum on Technology and Society’s third annual AI April, a month of presentations, events, and podcasts dedicated to AI capabilities, applications, future impacts, challenges, and more.

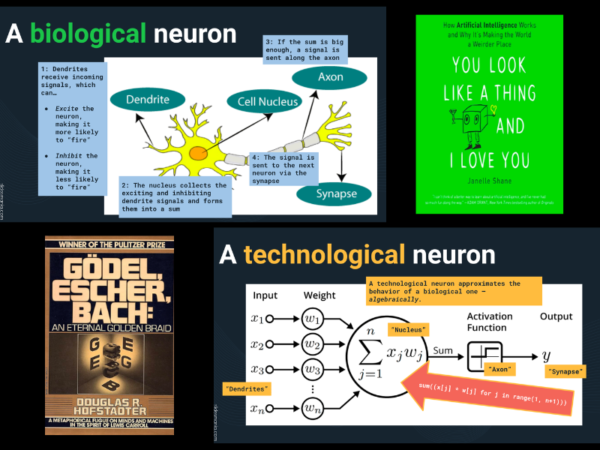

My presentation will start with a brief history of AI, as well as the general principles of how “old school” AI works versus “new school” AI…

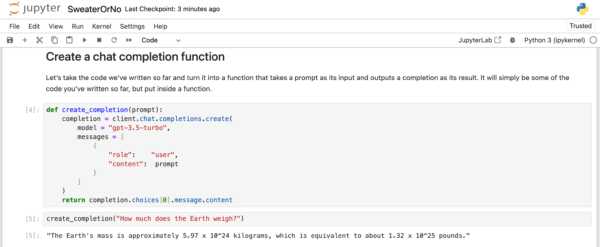

…but we’ll quickly dive into building Sweater or No, a quick little AI application that tells you if you should wear a sweater, based on your current location. Here’s a screenshot of some of the code we’ll build:

This is a FREE online session, so you don’t have to be in Austin to participate. I’m not in Austin, but Tampa Bay, and you can join in from anywhere!

You need to register to participate — here’s the registration page. I hope to see you there!