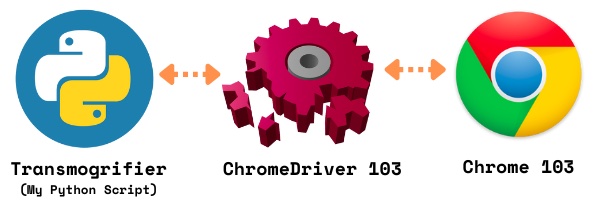

The ChromeDriver 103 bug

If you had an application or script that uses Selenium and ChromeDriver to control or automate instances of Chrome or Chromium, it’s probably not working right now. Instead, you’re probably seeing error messages that look like this:

Message: unknown error: cannot determine loading status

from unknown error: unexpected command response

(Session info: chrome=103.0.5060.53)

Stacktrace:

0 chromedriver 0x000000010fb6f079 chromedriver + 4444281

1 chromedriver 0x000000010fafb403 chromedriver + 3970051

2 chromedriver 0x000000010f796038 chromedriver + 409656

...and on it goes...The culprit is ChromeDriver 103, and I wrote about it a couple of days ago in a post titled Why your Selenium / ChromeDriver / Chrome setup stopped working.

ChromeDriver 103 — or more accurately, ChromeDriver 103.0.5060.53 — works specifically with Chrome/Chromium 103.0.5060.53. If you regularly update Chrome or Chromium and use ChromeDriverManager to keep ChromeDriver’s version in sync with the browser, you’ve probably updated to ChromeDriver 103.0.5060.53, which has a causes commands to ChromeDriver to sometimes fail.

The fix

Luckily, the bug has been fixed in ChromeDriver 104, which works specifically with Chrome 104. This means that if you update to Chrome and ChromeDriver 104, your Selenium / ChromeDriver / Chrome setup will work again.

The challenge is that Chrome 104 is still in beta. As I’m writing this, the Google Chrome Beta site is hosting an installer for Chrome 104, or more accurately, Chrome 104.0.5112.20. The application has the name Google Chrome Beta and is considered a separate app from Google Chrome. This means that you can have the current release and the beta version installed on your machine at the same time.

Once you’ve installed Chrome Beta, you just need to make your Selenium/ChromeDriver application or script use the appropriate version of ChromeDriver. Here’s how I did it in Transmogrifier, my Python script that helps me assemble the Tampa Bay Tech Events list:

from selenium import webdriver

from selenium.webdriver.chrome.options import Options

from selenium.webdriver.chrome.service import Service

from webdriver_manager.chrome import ChromeDriverManager

// 1

option = Options()

option.binary_location='/Applications/Google Chrome Beta.app/Contents/MacOS/Google Chrome Beta'

// 2

driver = webdriver.Chrome(service=Service(ChromeDriverManager(version='104.0.5112.20').install()), options=option)Here are some explanation that match the number comments in the code above:

- These lines create an instance of the

Optionsclass, which we’re using to specify the directory where the Chrome beta app can be found. We’ll use the instance,options, when we createdriver, the object that controls the Chrome beta app. - This constructor creates a

WebDriver.Chromeobject which will control the Chrome beta app. Theserviceparameter specifies that the driver should be an instance of ChromeDriver 104, and that it should be installed if it isn’t already present on the system. Theoptionsparameter specifies that ChromeDriver should drive the version of Chrome located at the directory path specified in theoptionobject: the Chrome beta app.

Once that’s done, I can proceed with my script. Here’s a simplified version of the start of my Transmogrifier script:

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

// Load the web page whose URL is `url` into

// the browser under script control

driver.get(url)

// Execute any scripts on the page so that

// we can scrape the final rendered version

html = driver.execute_script('return document.body.innerHTML')

// And now it’s time to scrape!

soup = BeautifulSoup(html, 'html.parser')

// ...the rest of the code goes here...Hope this helps!