I don’t agree with his takes on masks (guess) and testoterone (a bit too Jordan Peterson/Joe Rogan-adjacent for my liking), but I think he’s spot on with the observation above.

I don’t agree with his takes on masks (guess) and testoterone (a bit too Jordan Peterson/Joe Rogan-adjacent for my liking), but I think he’s spot on with the observation above.

Here’s it is: The final weekly list of tech, entrepreneur, and nerd events for Tampa Bay and surrounding areas for 2021! This one’s for the week of Monday, December 27 through Sunday, January 2, 2022.

This is a weekly service from Tampa Bay’s tech blog, Global Nerdy! For the past four years, I’ve been compiling a list of tech, entrepreneur, and nerd events happening in Tampa Bay and surrounding areas. There’s a lot going on in our scene here in “The Other Bay Area, on the Other West Coast”!

As far as event types go, this list casts a rather wide net. It includes events that would be of interest to techies, nerds, and entrepreneurs. It includes (but isn’t limited to) events that fall under the category of:

By “Tampa Bay and surrounding areas”, this list covers events that originate or are aimed at the area within 100 miles of the Port of Tampa. At the very least, that includes the cities of Tampa, St. Petersburg, and Clearwater, but as far north as Ocala, as far south as Fort Myers, and includes Orlando and its surrounding cities.

Keep in mind that many people schedule their events “autopilot” — every week, fortnight, or month on the same day, while forgetting that one of those days will happen on a holiday. Double-check any scheduled event with its organizers this week, especially if it’s scheduled for New Year’s Eve or New Year’s Day.

This list includes in-person events as well as online events. Omicron’s out there, so be smart and responsible — get your booster, mask up in crowds, and we can get back to what passes for normal sooner!

I try to keep this list up-to-date. I add new events as soon as I hear about them, so be sure to check this page often!

Have a wonderful holiday — and if you celebrate Christmas, have a merry Christmas — and have a happy new year!

| Group | Event Name | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Get More Targeted Instagram Followers in Tampa | |

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Facebook Marketing Tips, Tricks & Tools in Tampa | |

| Thinkful Tampa | Thinkful Webinar || Intro To Data Analytics: Tableau Basics | 12:00 PM to 1:30 PM EST |

| Thinkful Tampa | Thinkful Webinar || Data Analytics: Tools of the Trade | 8:00 PM to 9:30 PM EST |

| Headquarters Coworking – Kissimmee | Marketing Manager MeetUp : M3 | 11:00 AM |

| The Tampa Chapter of the Society for the Exploration of Play | Critical Hit Games: Board Game Night | 5:30 PM |

| Entrepreneurs Empower Empire | Official Meeting | 11:30 AM |

| Entrepreneurs & Business Owners of Sarasota & Bradenton | Virtual Networking Lunch Monday & Wednesday | 11:30 AM |

| Young Professionals of Tampa Bay Networking Group | South Tampa Referrals | 11:30 AM |

| Christian Professionals Network Tampa Bay | Live Online Connection Meeting- Monday | 11:30 AM |

| Professional Business Networking with RGAnetwork.net | St. Pete Networking Lunch! Fords Garage! Monday’s | 11:30 AM |

| Tampa / St Pete Business Connections | South Tampa Professional Networking Lunch | 11:30 AM |

| West Orange Comics & Video Games | Magic Mondays | 5:00 PM |

| Board Game Meetup: Board Game Boxcar | Weekly Game Night! (Lazy Moon Location) | 6:00 PM |

| Beginning Web Development | Weekly Learning Session | 6:00 PM |

| Tampa Bay Gaming: RPG’s, Board Games & more! | Open Painting at Warehouse 51 | 6:00 PM |

| Tampa Bay Tabletoppers | Monday Feast & Game Night | 6:00 PM |

| Thoughtful Writing | Philosophy in Writing | 6:00 PM |

| Magic the Gathering Tampa/Brandon/St Pete | Commander Night | 6:00 PM |

| Critical Hit Games | MTG: Commander Open Play | 6:00 PM |

| Tampa – Sarasota – Venice Trivia & Quiz Meetup | Trivia Night – Off the Wagon Kitchen & Brewery Smartphone Trivia Game Show | 6:30 PM |

| Toastmasters District 48 | North Port Toastmasters Meets Online!! | 6:30 PM |

| South Florida Poker, Music & Entertainment Group | FREE Texas Holdem Poker Tournaments at Fireside Lounge & Billiards 7 PM Start | 7:00 PM |

| America’s TriviAddiction | 3 DAUGHTERS BREWING – LIVE TEAM TRIVIA – ST. PETERSBURG | 7:00 PM |

| Orlando Stoics | ONLINE: “Stoic Physics in Brief: The Universe, The Soul, and Death” | 7:00 PM |

| Nerd Night Out | NB Online Anime Watch Party | 7:00 PM |

| ShutterObi – Orlando Photography Group | Business & Marketing For Photographers – Taglines For Websites & Portfolios | 7:00 PM |

| 3D Printing Orlando | I just got a Resin Printer – NOW WHAT? | 7:00 PM |

| Learn-To-Trade Cryptocurrency (as seen on Orlando Sentinel) | Learn-To-Trade Q&A (0NLINE) | 7:00 PM |

| Forex Automation and Trading | Come Trade the Forex :: Crypto :: Stocks :: Investments | 7:00 PM |

| Nerdbrew Events | Anime Watch Party | 7:00 PM |

| Central Florida AD&D (1st ed.) Grognards Guild | World of Greyhawk: 1E One-Shots | 7:30 PM |

| Wesley Chapel, Trinity, New Tampa Business Professionals | Lutz, Wesley Chapel, New Tampa Virtual Networking Lunch | 9:00 AM |

| Tampa Flutter Meetup Group | In-Person Meetup | 6:00 PM |

| Group | Event Name | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Get More Targeted Instagram Followers in Tampa | |

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Facebook Marketing Tips, Tricks & Tools in Tampa | |

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] How to Write SEO Friendly Google Content in Tampa | |

| Independent Film Fans of Sarasota | Worth (2020) – on Netflix | 11:00 AM |

| Magic the Gathering Tampa/Brandon/St Pete | Commander Night | 6:00 PM |

| Orlando Board Gaming Weekly Meetup | South Orlando Friday Night Board Gaming | 6:00 PM |

| Orlando Adventurer’s Guild | [Online HISTORIC] Canon’s Custom Campaign Moonsea Tour – DM Canon (Tier 3) | 7:00 PM |

| Nerdbrew Events | Happy Brew Year Party 2021 | 7:00 PM |

| Nerd Night Out | NerdBrew’s Happy Brew Year Party 2021 | 7:00 PM |

| Gen Geek | NYE @Hardrock casino (L Bar) | 9:00 PM |

| Group | Event Name | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Get More Targeted Instagram Followers in Tampa | |

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Facebook Marketing Tips, Tricks & Tools in Tampa | |

| Tampa Gaming Guild | Saturday Gaming | 10:00 AM |

| Gen Geek | Dim sum @Yummy house | 11:00 AM |

Let me know at joey@joeydevilla.com!

If you’d like to get this list in your email inbox every week, enter your email address below. You’ll only be emailed once a week, and the email will contain this list, plus links to any interesting news, upcoming events, and tech articles. Join the Tampa Bay Tech Events list and always be informed of what’s coming up in Tampa Bay!

Here’s your weekly list of tech, entrepreneur, and nerd events — plus a little area tech news — for Tampa Bay and surrounding areas for the week of Monday, December 20 through Sunday, December 26, 2021.

This is a weekly service from Tampa Bay’s tech blog, Global Nerdy! For the past four years, I’ve been compiling a list of tech, entrepreneur, and nerd events happening in Tampa Bay and surrounding areas. There’s a lot going on in our scene here in “The Other Bay Area, on the Other West Coast”!

As far as event types go, this list casts a rather wide net. It includes events that would be of interest to techies, nerds, and entrepreneurs. It includes (but isn’t limited to) events that fall under the category of:

By “Tampa Bay and surrounding areas”, this list covers events that originate or are aimed at the area within 100 miles of the Port of Tampa. At the very least, that includes the cities of Tampa, St. Petersburg, and Clearwater, but as far north as Ocala, as far south as Fort Myers, and includes Orlando and its surrounding cities.

Keep in mind that many people schedule their events “autopilot” — every week, fortnight, or month on the same day, while forgetting that one of those days will happen on a holiday. Double-check any scheduled event with its organizers this week, especially if it’s close to Christmas Day.

This list includes in-person events as well as online events. Omicron’s out there, so be smart and responsible — get your booster, mask up in crowds, and we can get back to what passes for normal sooner!

I try to keep this list up-to-date. I add new events as soon as I hear about them, so be sure to check this page often!

Have a wonderful holiday — and if you celebrate Christmas, have a merry Christmas!

| Group | Event Name | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Get More Targeted Instagram Followers in Tampa | |

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Facebook Marketing Tips, Tricks & Tools in Tampa | |

| Thinkful Tampa | Thinkful Webinar || Intro to JavaScript: Build a Virtual Pet | 12:00 PM to 1:30 PM EST |

| Thinkful Tampa | Thinkful Webinar || Bootcamp Alumni Success Secrets | 6:00 PM to 7:30 PM EST |

| Gen Geek | St pete pier beach and dinner | 4:30 PM |

| Brandon and Seffner area AD&D Group | 1st ed AD&D Campaign. | 6:00 PM |

| The Pinellas County Young “Professionals” | Brazilian Zouk on the Riverwalk | 6:00 PM |

| America’s TriviAddiction | BAYSCAPE BISTRO AT HERITAGE ISLES – NEW TAMPA – LIVE TEAM TRIVIA !!! | 6:30 PM |

| Modern Minimalism | Cal Newport’s book “Digital Minimalism” (Chap. 5 continued) | 7:00 PM |

| Learn-To-Trade Cryptocurrency (as seen on Orlando Sentinel) | Learn-To-Trade Stocks, Options & ETFs- (ONLINE) | 7:00 PM |

| Group | Event Name | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Get More Targeted Instagram Followers in Tampa | |

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Facebook Marketing Tips, Tricks & Tools in Tampa | |

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] How to Write SEO Friendly Google Content in Tampa | |

| Project Codex: Orlando Junior Developers | Virtual Coffee | 9:00 AM |

| Oviedo Middle Aged Gamers (OMAG) | Tabletop: Friday Board Game Night | 7:00 PM |

| Orlando Stoics | ONLINE: How To Think Like A Roman Emperor (Chapter 7 continued) | 7:00 PM |

Make the most of this day! I’m going to have dinner with local family in person and FaceTime with family in Toronto.

| Group | Event Name | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Get More Targeted Instagram Followers in Tampa | |

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Facebook Marketing Tips, Tricks & Tools in Tampa | |

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] How to Write SEO Friendly Google Content in Tampa | |

| Thinkful Tampa | Thinkful Webinar || What Tech Career Is Right For Me? | 12:00 PM to 1:30 PM EST |

| Thinkful Tampa | Thinkful Webinar || Enhancing Your Career With Mindfulness | 6:00 PM to 7:30 PM EST |

| Critical Hit Games | D&D Adventurers League | 2:00 PM |

| Learn-To-Trade Cryptocurrency (as seen on Orlando Sentinel) | Learn-To-Trade Forex & Cryptos – (ONLINE) | 5:00 PM |

| Tampa Hackerspace | Sew Awesome! (Textile Arts & Crafts) | 5:30 PM |

| Tampa Hackerspace | Let’s Learn to Turn Pens! | 7:00 PM |

Let me know at joey@joeydevilla.com!

If you’d like to get this list in your email inbox every week, enter your email address below. You’ll only be emailed once a week, and the email will contain this list, plus links to any interesting news, upcoming events, and tech articles. Join the Tampa Bay Tech Events list and always be informed of what’s coming up in Tampa Bay!

Here’s your weekly list of tech, entrepreneur, and nerd events — plus a little area tech news — for Tampa Bay and surrounding areas for the week of Monday, December 13 through Sunday, December 19, 2021.

This is a weekly service from Tampa Bay’s tech blog, Global Nerdy! For the past four years, I’ve been compiling a list of tech, entrepreneur, and nerd events happening in Tampa Bay and surrounding areas. There’s a lot going on in our scene here in “The Other Bay Area, on the Other West Coast”!

As far as event types go, this list casts a rather wide net. It includes events that would be of interest to techies, nerds, and entrepreneurs. It includes (but isn’t limited to) events that fall under the category of:

By “Tampa Bay and surrounding areas”, this list covers events that originate or are aimed at the area within 100 miles of the Port of Tampa. At the very least, that includes the cities of Tampa, St. Petersburg, and Clearwater, but as far north as Ocala, as far south as Fort Myers, and includes Orlando and its surrounding cities.

This list includes in-person events as well as online events. The COVID-19 numbers are dropping sharply, but be smart and responsible — get your shots, mask up in crowds, and we can get back to what passes for normal sooner!

I try to keep this list up-to-date. I add new events as soon as I hear about them, so be sure to check this page often!

| Group | Event Name | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Coachieve | Entrepreneur Crash Course – Tampa | |

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Get More Targeted Instagram Followers in Tampa | |

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Facebook Marketing Tips, Tricks & Tools in Tampa | |

| Tampa Bay Tech Career Advice Forum | Job Seeker Coffee Talk | 9:00 AM |

| Entrepreneurs & Business Owners of Sarasota & Bradenton | Virtual Networking Lunch Monday & Wednesday | 11:30 AM |

| Professional Business Networking with RGAnetwork.net | Virtual Networking Lunch | 11:30 AM |

| Young Professionals of Tampa Bay Networking Group | South Tampa Referrals | 11:30 AM |

| Tampa / St Pete Business Connections | South Tampa Professional Networking Lunch | 11:30 AM |

| Wesley Chapel, Trinity, New Tampa Business Professionals | Lutz, Wesley Chapel, New Tampa Virtual Networking Lunch | 11:30 AM |

| Orlando Video & Post Production Meetup | Virtual Event: Video – Wireless Microphone Techniques | 11:30 AM |

| Christian Professionals Network Tampa Bay | Live Online Connection Meeting- Monday | 11:30 AM |

| Thinkful Tampa | Thinkful Webinar || Intro to HTML & CSS: Build Your Own Website | 12:00 PM to 1:30 PM EST |

| Entrepreneurs Empower Empire | Office Hour | 12:00 PM |

| Tampa St Pete Stocks and Options Trading Group | Vantage Point – Weekly Market Recap & Outlook of Future Market Conditions | 2:00 PM |

| Tampa Bay Coalition of Reason | In Person – Tampa Bay Technology Center Holiday Potluck | 4:30 PM |

| West Orange Comics & Video Games | Magic Mondays | 5:00 PM |

| AWS User Groups of Florida – Tampa | AWS Control Tower | 5:00 PM |

| The Tampa Chapter of the Society for the Exploration of Play | Critical Hit Games: Board Game Night | 5:30 PM |

| Board Game Meetup: Board Game Boxcar | Weekly Game Night! (Lazy Moon Location) | 6:00 PM |

| Critical Hit Games | MTG: Commander Open Play | 6:00 PM |

| Lakeland Black Professionals | LBP Dec Virtual Meeting | 6:00 PM |

| Magic the Gathering Tampa/Brandon/St Pete | Commander Night | 6:00 PM |

| Tampa Bay Tabletoppers | Monday Feast & Game Night | 6:00 PM |

| Beginning Web Development | Weekly Learning Session | 6:00 PM |

| St. Petersburg Crypto Investors and Miners Club | NFT Strategies for Investors | 6:00 PM |

| Thoughtful Writing | Philosophy in Writing | 6:00 PM |

| Tampa Bay Gaming: RPG’s, Board Games & more! | MTG: Commander Open Play (At Critical Hit Games) | 6:00 PM |

| Toastmasters District 48 | North Port Toastmasters Meets Online!! | 6:30 PM |

| Tampa – Sarasota – Venice Trivia & Quiz Meetup | Trivia Night – Off the Wagon Kitchen & Brewery Smartphone Trivia Game Show | 6:30 PM |

| Nerdbrew Events | Anime Watch Party | 7:00 PM |

| Brandon WordPress Meetup | TBA: Regular WordPress Meeting | 7:00 PM |

| South Florida Poker, Music & Entertainment Group | FREE Texas Holdem Poker Tournaments at Fireside Lounge & Billiards 7 PM Start | 7:00 PM |

| Learn-To-Trade Cryptocurrency (as seen on Orlando Sentinel) | Learn-To-Trade Q&A (0NLINE) | 7:00 PM |

| Forex Automation and Trading | Come Trade the Forex :: Crypto :: Stocks :: Investments | 7:00 PM |

| Orlando Stoics | Stoics v. Skeptics: What is Knowledge? | 7:00 PM |

| Tampa Flutter Meetup Group | In-Person Meetup | 7:00 PM |

| Toastmasters District 48 | South Tampa invites you to our Holiday Party 7p.m. at 717 South Howard Ave! | 7:00 PM |

| Tampa Hackerspace | Learn to Solder Holiday Edition — Make a Christmas Tree or Menorah | 7:00 PM |

| Central Florida AD&D (1st ed.) Grognards Guild | World of Greyhawk: 1E One-Shots | 7:30 PM |

| Thinkful Tampa | Thinkful Webinar | UX/UI Design: Wireframes and Prototypes | 8:00 PM to 9:30 PM EST |

| Thinkful Tampa | Careers in Tech | Thinkful Webinar | UX/UI Design: Wireframes and Prototypes | 8:00 PM |

=== Blog ===

Let me know at joey@joeydevilla.com!

If you’d like to get this list in your email inbox every week, enter your email address below. You’ll only be emailed once a week, and the email will contain this list, plus links to any interesting news, upcoming events, and tech articles. Join the Tampa Bay Tech Events list and always be informed of what’s coming up in Tampa Bay!

The End of Year Tech Meetup Extravaganza for Tampa Bay’s tech community happens tonight at 5:30 at on the lawn at Armature Works! I’ll be there, and if you can make it, you should come join us!

Here are a couple of tips to help you make the most of the event. I’ll see you there!

If you feel that your social skills are a bit rusty from over a year’s worth of quarantining, don’t worry — we’re all feeling that way.

If you need proof, here’s a short list of articles on the topic of dealing with post-pandemic social awkwardness:

If you’re feeling anxious about meeting up with people because you think you’ve forgotten how to socialize outside the bounds of a Zoom or Teams chat, remember that we’re all in the same situation. Relax and enjoy the opportunity to talk with people face-to-face again.

When meeting new people, especially at a tech event, you’re going to hear this question:

“What do you do?”

Many people, when asked this question, find it hard to come up with an answer on the spot. You might want to give some thought about what you’d like to give as your answer.

It should be quick — 15 seconds, and ideally, shorter. It’s not supposed to be your life story, but a little pleasantry that gives the people you’re meeting an idea of who you are and what you’re all about. Think of it as an “elevator pitch” for yourself.

You get bonus points if you can make it so that your self-introduction invite people to find out more about you. Susan RoAne, author of How to Work a Room (a book I recommend) likes to tell a story about someone she met whose one-liner was “I help rich people sleep at night”. That’s more interesting than “I’m a financial analyst”.

A lot of us haven’t seen each other in person since the spring of 2020, and it’s only natural that this question will come up:

“What have you been up to?”

I’ll admit it — here’s what I remember doing during way back during the start of the plague:

March 2020 was eighteen months ago, and thanks to the pandemic, it feels like a much longer stretch of time — especially the beginning, when the lockdown gave the days a certain monotonous quality.

Before the event, or at least on your way there, you might find it helpful to work on a rough idea of the “What I’ve been up to during the quarantine” story you’d like to tell.

That story doesn’t have to be a fully fleshed-out screenplay of your life during the plague. All you really need are a couple of points that you’re comfortable talking about, any of which could be a good starting point for a conversation to get reacquainted with old friends or get acquainted with new ones.

Remember that telling your “What I’ve been up to” story is about catching up, not competition. Unfortunately, a lot of hustle culture proponents spent the pandemic pushing the idea that the only right way to spend the lockdown was to master a new skill or start of new business. Many people lost their jobs, were suddenly in homes that were full all the time, adjusted to school being at home, lost friends and family, or faced other challenges that were either brought about or made worse by COVID. You shouldn’t feel bad if you didn’t become a productivity dynamo over the past 18 months, and you shouldn’t think badly of others if they didn’t either.

If this is your nightmare…

…the steps below are how you handle it:

Feel free to join me in at any conversational circle I’m in! I always keep an eye on the periphery for people who want to join in, and I’ll invite them.

This is especially true at an event like this, which is happening in a public venue rather than being a closed event in a convention hall or someone’s house. It’s up to all of us who are attending to make this get-together work.

One of the best ways to be a “guest host” is to make introductions, say “hello” to people who are by themselves and seem to be looking for a conversation, giving directions to places like the bathroom, and generally making people more comfortable. It’s not just good karma, but it’s also a good way to help build the tech community and promote yourself.

There often comes a time when you meet someone at an event like this and want to add them to your professional contacts. There was once a time when you’d do this by exchanging business cards…

…but these days, all you need is a smartphone, LinkedIn, and a contact info-sharing technique that LinkedIn should publicize more.

Suppose you want to exchange contact info with someone and want to do it with little fuss. Do the following…

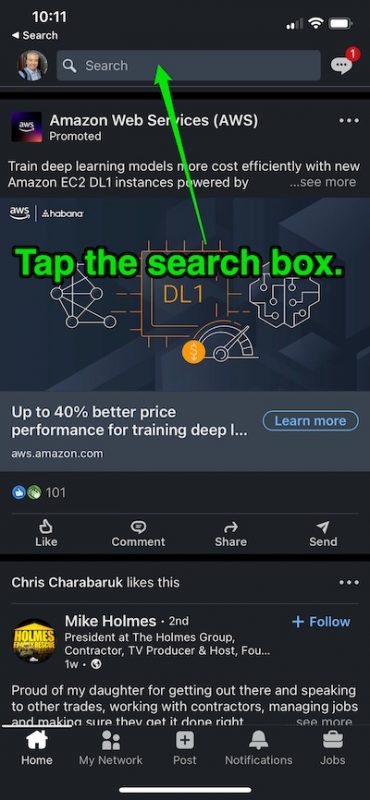

Open LinkedIn on your phone, then tap the search box at the top of the screen:

You’ll be taken to the search screen. Tap the icon on the right side of that screen’s search box:

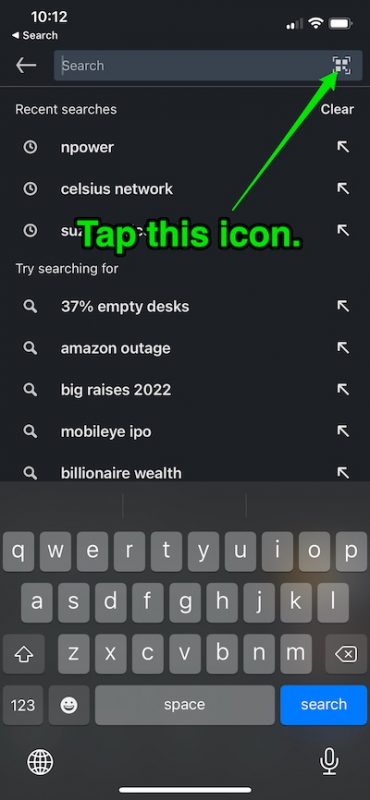

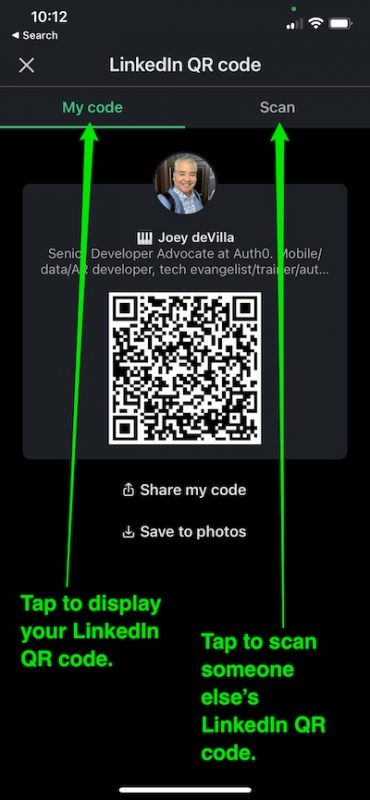

You’ll be taken to this screen:

At this point, you can make a connection:

Once you scan someone’s QR code, LinkedIn will take you to their profile, at which point you can press the Connect button and make a connection.

Here’s your weekly list of tech, entrepreneur, and nerd events — plus a little area tech news — for Tampa Bay and surrounding areas for the week of Monday, December 6 through Sunday, December 12, 2021.

This is a weekly service from Tampa Bay’s tech blog, Global Nerdy! For the past four years, I’ve been compiling a list of tech, entrepreneur, and nerd events happening in Tampa Bay and surrounding areas. There’s a lot going on in our scene here in “The Other Bay Area, on the Other West Coast”!

As far as event types go, this list casts a rather wide net. It includes events that would be of interest to techies, nerds, and entrepreneurs. It includes (but isn’t limited to) events that fall under the category of:

By “Tampa Bay and surrounding areas”, this list covers events that originate or are aimed at the area within 100 miles of the Port of Tampa. At the very least, that includes the cities of Tampa, St. Petersburg, and Clearwater, but as far north as Ocala, as far south as Fort Myers, and includes Orlando and its surrounding cities.

This list includes in-person events as well as online events. The COVID-19 numbers are dropping sharply, but be smart and responsible — get your shots, mask up in crowds, and we can get back to what passes for normal sooner!

I try to keep this list up-to-date. I add new events as soon as I hear about them, so be sure to check this page often!

| Group | Event Name | Time |

|---|---|---|

| Coachieve | Entrepreneur Crash Course – Tampa | |

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Get More Targeted Instagram Followers in Tampa | |

| Brandon Leibowitz from SEO Optimizers | [Free Masterclass] Facebook Marketing Tips, Tricks & Tools in Tampa | |

| Tampa Bay Tech Career Advice Forum | Job Seeker Coffee Talk | 9:00 AM |

| Orlando Unity Developers Group | Unity Fundamentals Class Series – Class 1 – Unity Editor Interface | 10:00 AM |

| MilitaryX | Tampa Job Fair – Tampa Career Fair | 11:00 AM to 2:00 PM EST |

| Option Trading Strategies (Tampa Bay area) Meetup Group | Option Trading Strategies Meetup (Online) | 11:00 AM |

| Tampa / St Pete Business Connections | South Tampa Professional Networking Lunch | 11:30 AM |

| Christian Professionals Network Tampa Bay | Live Online Connection Meeting- Monday | 11:30 AM |

| Entrepreneurs & Business Owners of Sarasota & Bradenton | Virtual Networking Lunch Monday & Wednesday | 11:30 AM |

| Wesley Chapel, Trinity, New Tampa Business Professionals | Lutz, Wesley Chapel, New Tampa Virtual Networking Lunch | 11:30 AM |

| Young Professionals of Tampa Bay Networking Group | South Tampa Referrals | 11:30 AM |

| Professional Business Networking with RGAnetwork.net | South Tampa Business Networking Lunch | 11:30 AM |

| Professional Business Networking with RGAnetwork.net | Virtual Networking Lunch | 11:30 AM |

| Thinkful Tampa | Thinkful Webinar || Intro To Data Analytics: Tableau Basics | 12:00 PM to 1:30 PM EST |

| Tampa St Pete Stocks and Options Trading Group | Vantage Point – Weekly Market Recap & Outlook of Future Market Conditions | 2:00 PM |

| West Orange Comics & Video Games | Magic Mondays | 5:00 PM |

| Entrepreneurs & Startups – Bradenton Networking & Education | Holiday Event! | 5:30 PM |

| The Tampa Chapter of the Society for the Exploration of Play | Critical Hit Games: Board Game Night | 5:30 PM |

| Beginning Web Development | Weekly Learning Session | 6:00 PM |

| Critical Hit Games | MTG: Commander Open Play | 6:00 PM |

| Board Game Meetup: Board Game Boxcar | Weekly Game Night! (Lazy Moon Location) | 6:00 PM |

| We Write Here Black and Women of Color Writing Group | Virtual Writing Get Downs | 6:00 PM |

| Tampa Bay Tabletoppers | Monday Feast & Game Night | 6:00 PM |

| Orlando Adventurer’s Guild | [FR] Waterdeep: Dragon Heist – DM Carson (Tier 1) | 6:00 PM |

| Tampa Bay Gaming: RPG’s, Board Games & more! | MTG: Commander Open Play (At Critical Hit Games) | 6:00 PM |

| Thoughtful Writing | Philosophy in Writing | 6:00 PM |

| Magic the Gathering Tampa/Brandon/St Pete | Commander Night | 6:00 PM |

| Tampa – Sarasota – Venice Trivia & Quiz Meetup | Trivia Night – Off the Wagon Kitchen & Brewery Smartphone Trivia Game Show | 6:30 PM |

| Toastmasters District 48 | North Port Toastmasters Meets Online!! | 6:30 PM |

| Tampa# – C# and .NET | Group Code Challenge [Virtual] | 7:00 PM |

| Nerdbrew Events | Anime Watch Party | 7:00 PM |

| South Florida Poker, Music & Entertainment Group | FREE Texas Holdem Poker Tournaments at Fireside Lounge & Billiards 7 PM Start | 7:00 PM |

| Toastmasters Division E | Lakeland (FL) Toastmasters Club #2262 | 7:00 PM |

| Nerd Night Out | NB Online Anime Watch Party | 7:00 PM |

| Orlando Stoics | ONLINE: “Ajahn Chah: Training the Heart and Mind” (Part 3) | 7:00 PM |

| Tampa Flutter Meetup Group | In-Person Meetup | 7:00 PM |

| Orlando Investors & Trader Stocktwits Meetup Group | INVESTORS & TRADERS Drinks Night! – Food, Drinks, and Swag! Hosted by Stocktwits | 7:00 PM |

| Central Florida AD&D (1st ed.) Grognards Guild | World of Greyhawk: 1E One-Shots | 7:30 PM |

| Thinkful Tampa | Thinkful Webinar | Intro to UX/UI Design: User Research | 8:00 PM to 9:30 PM EST |

Let me know at joey@joeydevilla.com!

If you’d like to get this list in your email inbox every week, enter your email address below. You’ll only be emailed once a week, and the email will contain this list, plus links to any interesting news, upcoming events, and tech articles. Join the Tampa Bay Tech Events list and always be informed of what’s coming up in Tampa Bay!