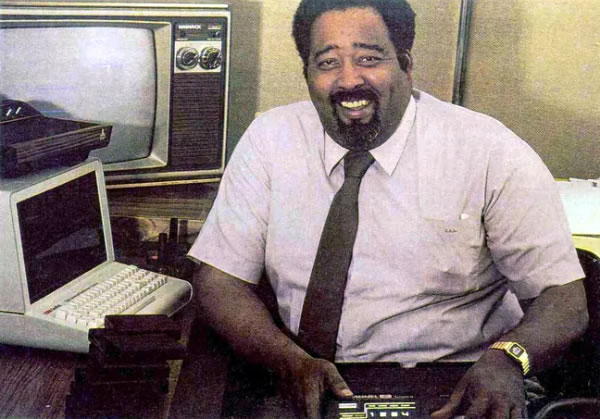

Fellow gamers, pay tribute to the gentleman in the photo above. He’s Gerald “Jerry” Lawson, and he was in charge of creating the first videogame console that could play different games by using interchangeable ROM cartridges:

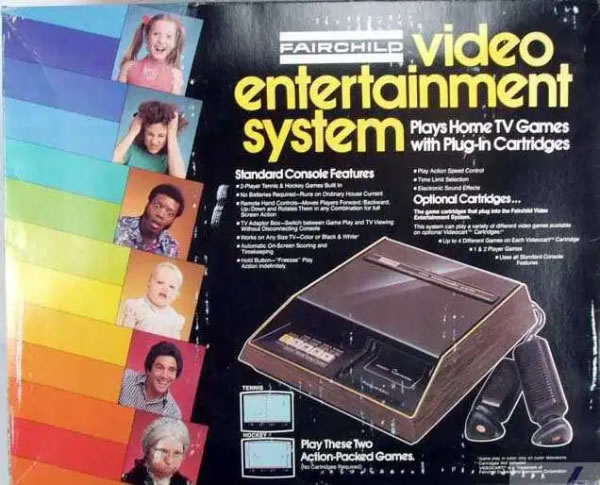

That console was the Fairchild Channel F (also known as the Fairchild Video Entertainment System), which debuted in November 1976, almost a full a year before the better-remembered Atari VCS (later renamed the Atari 2600).

The Fairchild Channel F console. Tap the photo to see it at full size.

Here’s a quick run-down of its specs:

| Feature | Notes |

| CPU | Fairchild F8 8-bit microprocessor running at 1.79 MHz |

| RAM |

|

| Video |

|

| Sound | System could generate beeps at three different frequencies:

|

A younger Jerry Lawson. In case you were wondering, that thing in his hand is a slide rule or “slipstick” in engineering slang, an analog calculator that made use of logarithms to perform multiplication and division. You should be thankful we don’t need them anymore.

Lawson was born in Brooklyn on December 1, 1940 and grew up in Queens. His father was an avid reader of science books, and his mother was a city employee who also was president of the PTA at his nearly all-white school. He kept inspired in his studies with a picture of black scientist and inventor George Washington Carver.

He pursued a number of scientific and engineering interests as a boy, performing chemistry experiments and using ham radios. In his teens, he earned money repairing TVs, which was a little more hazardous in those days, as the cathode ray tube-based televisions of that era worked with extremely high voltages (I myself used to play with them as a teenager in some highly unrecommended ways).

In the early 1970s, Lawson joined the Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corporation in Silicon Valley as a design consultant who roved from project to project. One of the projects he worked on was the classic 1970s arcade videogame Demolition Derby (the Chicago Coin version, not the Midway version from the 1980s), which featured some surprisingly clever programming — the computer-controlled cars acted “smart” enough to try and dodge your attacks. In his spare time, he was a member of the legendary Homebrew Computer Club, where he was one of its two black members.

Lawson’s experience in videogames — a bleeding-edge and esoteric line of work at the time — led Fairchild to put him in charge of its videogame division. As leader of the team that created their console, he helped bring about the concept of game cartridges, a revolutionary concept at the time. In those days, consoles had their games “hard-wired” onto their circuit boards, and what you bought was what you got. He also oversaw the development of a new processor, the Fairchild F8, to power the system.

Unfortunately, the Channel F was eclipsed by the Atari 2600. Lawson left Fairchild in 1980 to found the videogame company Videosoft and also did consulting work.

Let’s all hold a controller in the air for Jerry Lawson, videogaming pioneer!

Find out more about Jerry Lawson

Here’s a 2018 video from Microsoft Developer, featuring Jerry’s children talking about their dad:

Here’s 1Life2Play’s tribute:

Here’s an ad for the Channel F from 1976:

Here’s a RetroManCave overview of the Channel F:

Here’s Erin Play’s review of the Channel F, which includes reviews of several cartrdiges:

And finally, here’s a three-party featuring Lawson speaking at the Computer History Museum in 2006: