This article originally appeared in Canadian Developer Connection.

EnergizeIT

Our cross-Canada tour where we showcase some up-and-coming-really-soon stuff like Windows 7 and Windows Server 2008 R2 starts today in Montreal! The events for the next couple of days are…

Our cross-Canada tour where we showcase some up-and-coming-really-soon stuff like Windows 7 and Windows Server 2008 R2 starts today in Montreal! The events for the next couple of days are…

For more about EnergizeIT, see this earlier post or visit the EnergizeIT site.

Ignite Your Career

Today at noon (Eastern), we’ll be presenting the third webcast in the Ignite Your Career series, titled How to Establish and Maintain a Healthy Work/Life Balance. You can find out more about this particular episode here, and you can sign up here – remember, it’s free! – with your Windows Live ID.

Today at noon (Eastern), we’ll be presenting the third webcast in the Ignite Your Career series, titled How to Establish and Maintain a Healthy Work/Life Balance. You can find out more about this particular episode here, and you can sign up here – remember, it’s free! – with your Windows Live ID.

The two previous webcasts have been posted online for you to listen to anytime, and we’ve got three more webcasts as well. For more details, check out the Ignite Your Career site.

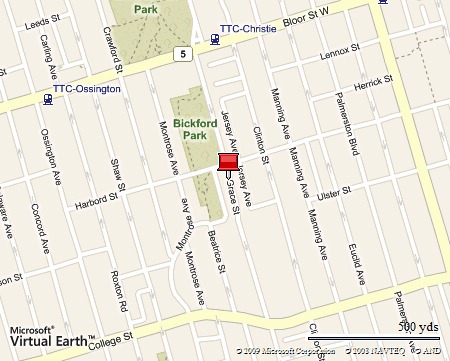

Coffee and Code

We had Coffee and Code sessions in Calgary and Toronto on Friday, one in Montreal yesterday, and more are on the way! As we evangelists go across the country for the EnergizeIT tours, we’ll also be holding Coffee and Code events in those cities. Keep an eye on this blog or the Coffee and Code blog for a Coffee and Code near you!

Remember, Coffee and Code is one way we’re making ourselves more accessible to you. If you’ve got a question or comment about Microsoft, our tools and tech, programming, systems administration, the tech industry or anything else, please drop by to chat face-to-face and join us for a cup of your favourite hot beverage!

And yes, there’s a Coffee and Code this Friday in Toronto, with a location to be announced. Stay tuned!

Mix 09

Keep an eye out for announcements from the Mix 09 conference taking place in Las Vegas from Wednesday to Friday. It’s devoted to the intersection of technology, design and the web, and it’s likely that you might hear some interesting bits of news coming from there…

Keep an eye out for announcements from the Mix 09 conference taking place in Las Vegas from Wednesday to Friday. It’s devoted to the intersection of technology, design and the web, and it’s likely that you might hear some interesting bits of news coming from there…

Mesh and MeshU

Mesh, Canada’s “Web 2.0 and Social Media/Marketing” conference and MeshU, the workshop day associated with the Mesh conference, posted their schedules yesterday. If you want to go to a conference feeaturing a Canadian perspective on the web and its business and tech opportunities, Mesh is the conference to catch.

You can find out more at the Mesh and MeshU sites or read my posting on Mesh and MeshU on my tech blog, Global Nerdy.

…and One More Thing…

Happy St. Patrick’s Day! I’d tell you to drink responsibly, but you already do that, right? Uh, right?