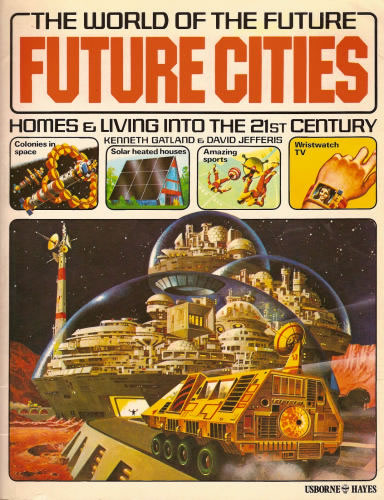

Back when I was a kid in the late 70s and early 80s, I loved the Usborne series of books about life in the future. Now that I’m living in the future, I’m trying to find these old books and see how many of their predictions of life today came true. The Usborne Guide to Computer and Video Games, which I pointed to in an earlier entry, was rather accurate in its predictions of what was in store for video and computer games. The future home tech featured in Usborne’s Future Cities: Homes and Living into the 21st Century (whose cover appears below) isn’t too far off the mark either; most of it would be easily found at your local Best Buy.

One section in Future Cities is titled Computers in the Home. It describes a home of future, as seen through the eyes of a British author dabbling in sci-fi in the late 1970s. Here’s its introduction:

Computers in the Home

The picture on the right takes you into the living room of a house in the future. The basics will probably be similar — windo9ws, furniture, carpet and TV. There will be one big change though — the number of electronic gadgets in use.

The same computer revolution which has resulted in calculators and digital watches could, through the 1980s and ’90s, revolutionise people’s living habits.

Television is changing from a box to stare at into a useful two-way tool. Electronic newspapers are already available — pushing the button on a handset lets you read ‘pages’ of news, weather, puzzles and quizzes.

TV-telephones should be a practical reality by the mid 1980s. Xerox copying over the telephone already exists. Combining the two could result in millions of office workers being able to work at home if they wish. There is little need to work in a central office if a computer can store records, copiers can send information from place to place and people can talk on TV-telephones.

Many people may prefer to carry on working in an office with others, but for those who are happy at home, the savings in travelling time would be useful. Even better would be the money saved on transport costs to and from work.

Pictured below is a scan of the two-page spread in which the Computers in the Home section appears. It points out some features in a future home, most of which you might find in your own living room today.

Click to see the full picture at full size.

Image courtesy of Miss Fipi Lele.

Here’s the accompanying text, with my commentary in italics:

The Electronic Household

This living room has many electronic gadgets which are either in use already or are being developed for people to buy in the 1980s.

1. Giant-size TV

Based on the designs already available, this one has a super-bright screen for daylight viewing and stereo sound system.

(Came true and even was surpassed in some ways. 42-inch plasma screens sell at Costco for about $1000 and TV isn’t just broadcast in stereo, but 5:1 surround.)

2. Electronic video movie camera

Requires no film, just a spool of tape. Within ten years video cameras like this could be replaced by 3-D holographic recorders.

(The bit about tape came true in the 80s and is surpassed today by recorders that write to magnetic and optical disk as well as solid-state memory. Holograms, a “science news” favourite that seemed to crop up in the news once a month, don’t have the future-appeal they did back then.)

3. Flat screen TV

No longer a bulky box, TV has shrunk to a thickness of less than five centimetres. This one is used to order shopping via a computerised shopping centre a few kilometres away. The system takes orders and indicates if any items are in stock.

(Strange how they separated “giant TV” from “flat screen” TV, as if it were an either-or-but-not-both choice. It’s come true, all right: the LCD monitor with which I’m making this entry is a mere 3 centimetres thick, and the head office of Amazon — this entry links to Future Cities in its catalog — is about 3000 kilometres away.)

4. Video disc player

Used for recording off the TV and for replaying favourite films.

(Came true and surpassed with DVDs, Tivo, movies-on-demand and the merging of disc players and videogames.)

5. Domestic robot rolls in with drinks.

One robot, the Quasar, is already on sale in the USA. Reports indicate that it may be little more than a toy, however, so it will be a few years before “Star Wars” robots tramp through our homes.

(Things didn’t turn out as predicted. The Quasar, pictured below, was much less than a toy. In fact, it turned out to be a hoax:

We do have the Roomba, though, and we do live in a world where a robot gladiator contest is a viable TV show.)

6. Mail slot

By 1990, most mail will be sent in electronic form. Posting a letter will consist of placing it in front of a copier at your home or post office. The electronic read-out will be flashed up to a satellite, to be beamed to its destination. Like many other electronic ideas, the savings in time and energy could be enormous.

(Two areas in which retro-future predictions break down are how we’ll communicate with our machines and how we’ll communicate with each other. Most models of electronic mail as perceived around 1980 was always some form of tele-copying, where you’d write or type your original letter, which would then be scanned into electronic form and then printed at the post office closest to the receiving party. Even the U.S. Postal Service envisioned this model, since they saw mail, whether physical or electronic as their rightful domain. Remind me to post and article about this sometime.)