Sometimes, you have to do more than just start from scratch. Sometimes, you have to burn the boats.

“Burning the boats” is an expression that comes from a story – some say legend — about Cortes, the Spanish Conquistador (and yes, the subject of Neil Young’s Cortez the Killer). Wishing to guarantee that his men would stay in Veracruz (which he’d just taken over from the Governor of Cuba) and only move forward into terra incognita without retreat, he ordered them to burn the ships that brought them to the New World. It was an extreme measure, but without the distraction of a way home, they committed themselves completely to business of exploring and conquering.

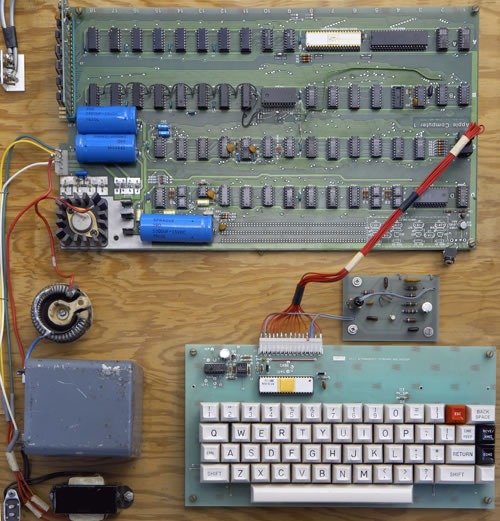

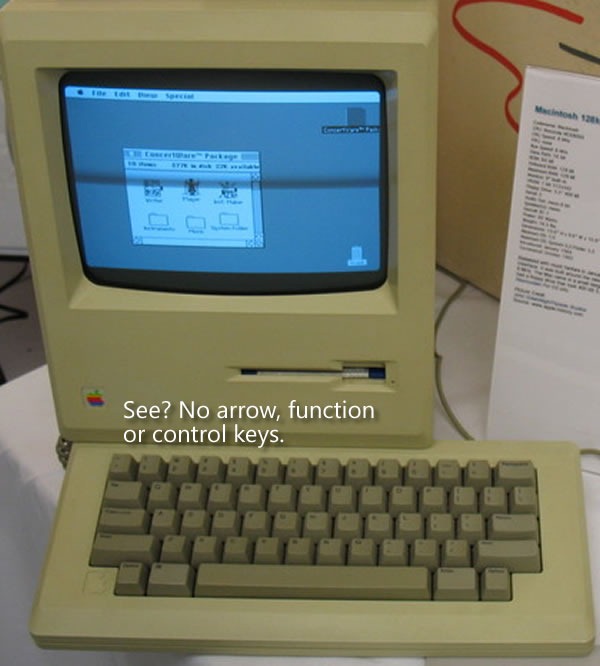

The Original Mac: No Arrow Keys

Bruce “Tog” Tognazzini, former user interface guy at Apple and the company formerly known as Sun, and now member of the Nielsen/Norman Group, wrote about how Apple burned the boats back when they released the original Macintosh in his 1992 book Tog on Interface and more recently in an article on his blog, AskTog.

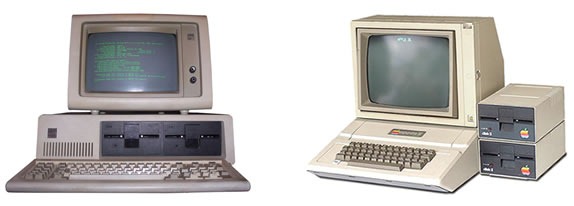

In 1984, the Macintosh represented a break from the dominant paradigm at the time: the command-line interface. Back then, you’d issue commands to a program these ways:

- Typing them in

- Using control-key combinations

- Using function keys

- Using the arrow keys to navigate

Software developers at the time had little experience developing for GUIs, which meant that there would be great temptation for them to simply develop apps for the Mac the way they did for other platforms. The software they’d end up writing would be a command-line app that just happened to run on the Mac.

Steve Jobs and Apple’s Macintosh team, an unconventional bunch who were said to have nary a classical computer science degree among them, thought that existing software sucked. I was 16 at the time, and I’d have to agree. In order to prevent straight ports of existing software to the Mac, they decided to “burn the boats” and make it difficult for developers to “go home” and simply rely on the UI techniques from the Old World. The first Mac keyboards didn’t just omit the function keys, they also left out the arrow keys:

Tog writes:

That was a big deal. Almost every application then in existence depended on the arrow keys (then called cursor keys) for navigation. With that one stroke, Steve reduced the number of apps that could be easily ported to the Mac from tens of thousands to zero, ensuring that this new computer would have a long and painful childhood.

It’s counterintuitive to want to have your creation go through a long and painful childhood, but there was a method to their madness. In “burning the boats” by getting rid of the function and arrow keys on which developers relied and taking away their “way home”, they forced developers to redesign and rewrite their applications to fit a mouse-driven graphical interface rather than a keyboard-driven command-line interface.

They eventually brought back the arrow keys about a year and a half later. By that point, developers had grown used to developing GUI apps that took advantage of the UI controls and mouse that we’ve come to know and love. The return of the arrow keys at that point would now be a welcome addition and convenience, rather than a dangerous temptation to return to “the old ways”.

It was a bold move, but when you’re making radical changes to the way things are done, bold moves are often required.

Windows Phone 7: No Copy and Paste

There’s been some talk about Windows Phone 7’s lack of copy and paste. It’s similar to the hue and cry about the original iPhone’s lack of copy and paste, and having been reminded by Tog’s article about the design decisions made for the original Mac, I can see the method to Microsoft’s madness.

“Copy and paste already exists in Windows,” people have said, “why not Windows Phone 7?”

The answer is simple: because Windows Phone 7 apps aren’t supposed to be like Windows apps. For non-enterprise, non-industrial use, the “Windows, but scaled down” approach of previous versions of Windows for phones, which goes under the name Windows Mobile, didn’t catch on (Windows Mobile still rules the roost for compact devices used in enterprises and industries, and will be supported for years to come). Hence Albert Shum’s completely different-from-the-desktop, and even different-from-other-phones Windows Phone 7 interface, which went by the codename “Metro”.

The use of copy and paste implies a keyboard-centric user interface, which isn’t what Windows Phone 7 is about. People often use their smartphones one-handed, with only their thumb to access the touchscreen. Windows Phone 7’s interface takes this usage into account, which is why it’s sensor-centric, and applications, should get their information from touch, gestures, accelerometers, location and other sensors where possible. By not including copy and paste in the first release, the Windows Phone team is “burning the boats” and asking developers “How do you write apps so that they don’t need intricate more-suited-to-the-desktop operations like copy and paste?”

(And yes, copy and paste will eventually find its way into Windows Phone 7, just as the arrow keys, function keys and even right-clicking found their way into the Mac.)

The same could be said for many other things that were purposely excluded from Windows Phone 7, such as the compact edition of SQL Server that was part of Windows Mobile. If you think about it, this design decision forces you to build apps so they store and retrieve data from the network, which makes sense, since phones are devices that network with both cellular and wifi.

Windows Phone 7 represents a radical shift in the way Microsoft stuff works, from a very minimalistic look to its task-centric organization. In order to make sure that people built apps that fit it, the Windows Phone 7 team had to burn the boats. It’s a bold move, but it’s the right one.

![Old Apple ][ ad featuring Ben Franklin: "What Kind of Man Owns His Own Computer?" Old Apple ][ ad featuring Ben Franklin: "What Kind of Man Owns His Own Computer?"](https://www.globalnerdy.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2009/04/apple-ben-franklin-ad-thumb.jpg)