This one’s a long one! You might want to get yourself a beverage or snack.

This week is Windows Mobile Incubation Week, a “jam session” taking place at The Empire’s Silicon Valley branch, where startups are invited to learn about Windows Mobile from Microsoft’s gurus and pick up some tricks from mobile industry gurus and venture capitalists. They’re also challenged to build Windows Mobile apps during the week, with prizes being awarded to winning participants. Admission to Mobile Incubation Week is free-as-in-beer; all you have to do is scrounge up the cash to cover your trip to the Valley and find a couch to crash on at night.

This week is Windows Mobile Incubation Week, a “jam session” taking place at The Empire’s Silicon Valley branch, where startups are invited to learn about Windows Mobile from Microsoft’s gurus and pick up some tricks from mobile industry gurus and venture capitalists. They’re also challenged to build Windows Mobile apps during the week, with prizes being awarded to winning participants. Admission to Mobile Incubation Week is free-as-in-beer; all you have to do is scrounge up the cash to cover your trip to the Valley and find a couch to crash on at night.

Even as a Sith Lord with Imperial backing, I don’t have the travel budget to get down to Silicon Valley to catch this event, and it’s likely that you don’t either. That doesn’t mean that you have to miss out on Mobile Incubation Week. I’ll be linking to all the blogs covering it and I’ll also be posting articles covering different aspects of Windows Mobile Development, some technical, some tactical. I hope it piques your interest in Windows Mobile; perhaps it might even get you started building apps for Windows Mobile phones.

In this first article, I talk about mobile development over the past few years (with a little detour into my own experiences) and the way I see the current state of Windows Mobile.

My First Mobile App

Back in early 2001, I bought a PalmOS-compatible Handspring Visor Platinum for $99 from my then-coworker at OpenCola, Steve Jenson. He’s always had ridiculous amounts of hardware in his house:

I used it regularly, but never got around to writing applications for it until early 2002. That’s when a number of companies building P2P software during the Bubble 1.0 era imploded and when OpenCola unceremoniously laid me off. I decided to put up my “consultant” shingle, and thanks to the network of contacts I’d built as OpenCola’s Developer Relations guy, it didn’t take long for me to dig up some clients.

A friend of mine who was now working for a big drug company’s ad agency asked if I could write a questionnaire app for PalmOS handhelds. It wasn’t anything too complicated: just give the user (who could either be a doctor or a patient) a series of questions and provide a response at the end based on their answers. The tasks seemed simple enough, and despite the fact that I’d never written a Palm app before, I took the job.

(For those of you new to the industry, you’ll find that that you will often be asked to do things that you’ve never done before or aren’t 100% sure you can do. One of the valuable skills that comes with experience is figuring out how far you can stretch yourself and your abilities with a project.)

I’d seen a couple of articles on developing for PalmOS in C, and they looked like more work than they were worth. An app that was made up of a single button that read “Hello World” took 3 or 4 pages of code to implement, most of which was what I call “preamble” – a lot of setup code and “scaffolding” to support the app, way more code than for the actual app itself. My client seemed to be testing the waters of Palm apps, so I figured I’d be asked to make lots of changes to the app along the way. I needed something that would let me build and modify Palm apps quickly.

My plan was to build the app with NS Basic/Palm, a Visual Basic-like development system for PalmOS. I’d heard about it before, and as an added bonus, they were based right here in Toronto. I picked up a copy directly from their offices in the morning, and by the end of the afternoon, I had a functioning version of the app. By the end of the next day, I had it polished. The day after that, I showed my work to the client, and a week after that, they cut me a cheque.

I thought I’d make a career for myself as a PalmOS developer, but after that initial success, no other clients approached me about building a Palm app for them. That was a bit of a disappointment; unlike many of my friends, who wanted to build system- or network-level software, I wanted to build software for people. I figured that the best platform for people-oriented software would be a computer that you had in your pocket with you all the time.

The Underused 1995-Era Computer in Your Pocket

One of the things that I noticed while building Palm apps in 2002 was that the machine specs were like the specs for desktops back in 1995, when I was building CD-ROM-based multimedia apps with Mackerel Interactive Multimedia. The desktops of 1995 had processor speeds in the double-digit megahertz, RAM in the single-digit megabytes and limited, if any, access to the internet – just like 2002-era PalmOS devices.

At the same time, there was a class of devices that was beginning to emerge – the smartphone, which combined the connectedness of mobile phones with the computing power of PDAs. The problem was trying to get apps onto them.

Back in late 2003, when I was just getting started as Tucows’ Tech Evangelist, I wrote an article grumbling about the state of mobile development. In spite of the fact that smartphones had the power of PDAs, the market for mobile apps seemed like a ghost town. There was a mish-mash of all sorts of mobile platforms, installing apps on your mobile form was more complicated than it should’ve been, and the telcos seemed to be doing their level best to keep apps off of phones, using the need to “keep the phone network secure” as their excuse.

“Imagine how far behind we’d be,” I wrote back then, “if we had to get our computer vendor’s permission every time we installed a new program on our desktops. That’s what it’s like for mobile apps.”

The Best Gaming Phone, 5 Years Ago

Near the end of 2003, this phone was supposed to be the thing that brought mobile gaming to the masses:

It was the Nokia N-Gage. There’s a good reason you probably never owned one, nor did anyone you know. While it had some decent specs, it was a pain for both developers and users alike:

- Pain for the developers: Not just anyone could develop for the N-Gage. You had to apply for permission to do so, which required you to have a track record of mobile game development, which probably ruled out a lot of potential developers in 2003. There was also the matter of the fee that you had to submit while applying for the privilege of being an N-Gage developer: the non-trivial sum of 10,000 Euro.

- Pain for the users: The buttons were notoriously bad – they used phone-grade buttons as opposed to game controller-grade ones, which made for a less-than-optimal gaming experience.

- More pain for the users: Here’s how Brighthand described the process of loading a game onto the N-Gage: “"In order to put a game into the system, you have to turn the phone off, take the back cover off, remove the battery, slide out the existing game, put the new one in, put the battery back in, replace the back cover, hold down the power button for several seconds, wait for the system to boot up, open the main menu, select the game, open it… And then your game starts loading."

- Even more pain for the users: The N-Gage sometimes suffered from “The White Screen of Death”, a phenomenon where your phone would spontaneously reboot thanks to a memory management issue arising from a design flaw. The fix was a firmware upgrade, for which Nokia decided to charge users.

I thought that the N-Gage had all kinds of portable personal computing uses, both for gaming and beyond, but there was no way I could develop for it. Besides, the telcos were still pretty adamant about not letting just anyone develop for smartphones.

So my plans to take on mobile development stayed shelved a little longer.

Predictions are Hard, Especially About the Future

Depending on where your loyalties, sympathies and platform preferences lie, you’re going to find the following headlines either LMAO-hilarious or stool-softeningly cringeworthy. Maybe it’s because I’m still a relatively new at Microsoft (I’ll have been there six months a week Monday), but I laughed and cringed at these headlines that vaingloriously predicted that The Empire would dominate the smartphone market:

- Industry Jumps on Windows Mobile 5.0 Bandwagon (May 12, 2005)

- Mobile Phones Will Overtake iPods, Says Gates (May 13, 2005)

- Microsoft Expects to Dominate Smartphones in Three Years (June 28, 2005)

“Dominate Smartphones in Three Years”, huh? Here’s what happened a mere two years later:

In the space of two years and one day, we’d gone from Microsoft triumphantly declaring that Windows Mobile would own the smartphone market to Microsoft’s most famous evangelist (well, former evangelist by that time) doing a victory pose at the Apple Store because he’d managed to get his paws on one of the first iPhones.

A good chunk of the iPhone’s success comes from Apple’s incredible marketing machine, but a bigger factor is that great products are their own marketing. The iPhone combines a great user experience and a centralized store, but far more important was the feeling that you were using something that was designed to be both beautiful and fun, not feasting on the table scraps thrown to you by a company who’d rather be making stuff for Fortune 500 executives.

The iPhone formula seems to be working. According to Kevin Tofel of the mobile device blog JK On the Run, Apple sold 3.3 million iPhones in 2007 and handily beat that sales figure in 2008 with 11.4 million, making them the mobile phone vendor that gained the most ground that year.

And Now, the Good News

It’s not all bad news for Windows Mobile or people who want to develop for it. For starters, Windows Mobile still represents a sizeable chunk of the mobile phone market. 18 million Windows Mobile licenses were sold in 2008, and they were sold to four out of the five largest mobile phone manufacturers in the world (in case you were wondering, Nokia is the holdout). LG has signed on to put Windows Mobile on 50 of its smartphone models. All told, that’s a big hardware ecosystem on which to deploy your mobile apps.

The smart moves that The Empire has been making with its various platforms, from Windows 7 to the web to XBox 360 to cloud computing, are also beginning to show in the form of Windows Mobile 6.5 (slated for release this year) and Windows Mobile 7 (due next year). The UI has been vastly improved; a lot of the UI lessons and ideas from Windows 7, XBox 360 and Surface seem to have made their way in:

And yes, there will be support not just for client apps that run on your WinMo phone, but Widgets – mini-web apps that run in a browser with just a border and no interface controls, a la Windows widgets or the iPhone’s web apps:

Paired with the improved user experience is an online store accessible from your Windows Mobile phone:

…and you still have the freedom to not use Windows Marketplace to sell your apps. I cover why that’s a good thing in the next and final section of this article.

Freedom

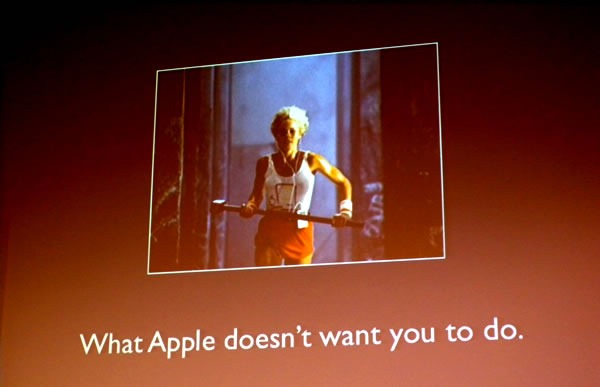

Let me show you some slides from Pete Forde’s recent presentation at MeshU, Is That an iPhone in Your Pocket, or are You Just Happy to See Me?. Namely, this section of his presentation:

The iPhone App Store is the only legal way to distribute iPhone apps, whether you’re selling them or giving them away. As a developer, you submit your applications to the App Store for review, and in around seven days, after which you are told whether your app has been accepted or rejected.

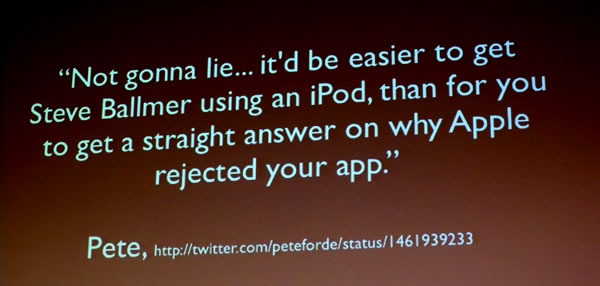

If your app is rejected, are you told the reasons why? Here’s Pete’s answer to that question:

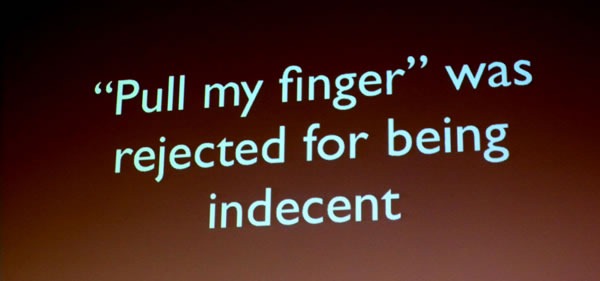

The people doing the reviews for the App Store are a toxic mix of Victorian-era prudish and Kafka-esque:

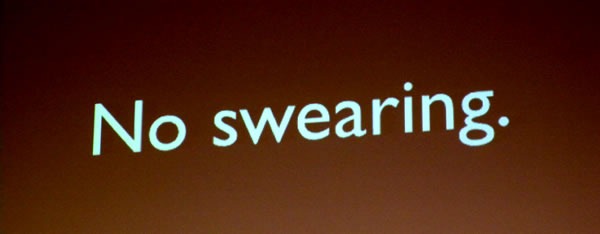

…and you can forget writing any David Mamet / Quentin Tarantino themed-apps:

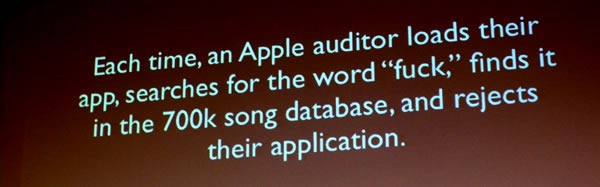

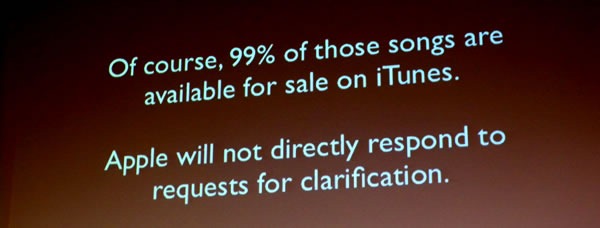

…and that’s not just “no swearing” in your apps; that’s also “no swear words” in any search results your app returns. Consider the problem faced by one hapless app developer:

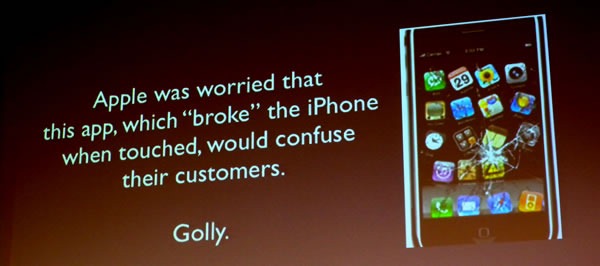

They’re also kind of uptight about certain novelty apps, such as the one that makes it look as though you’ve shattered your iPhone’s screen:

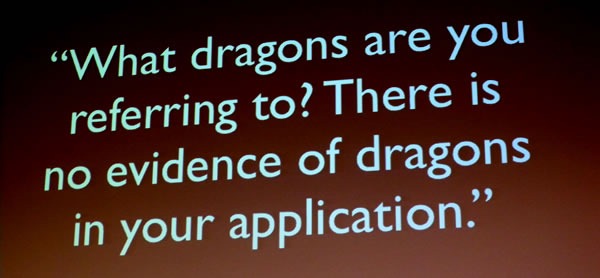

When you submit your app for review, whatever you do, don’t put any joke items in the feature list. One developer, when submitting an updated version of an app (yes, you have to submit updates for review) threw in a joke item in the feature list: more dragons! Here’s the response from the App Store review board:

The rest of Pete’s presentation was built around bypassing the App Store’s reviewer monkeys by building your iPhone apps as single-use browsers that were hard-wired to the web application where your app lived. That’s a workable solution for some apps, but not if you want to make use of the resources built into the iPhone.

While the Windows Mobile Marketplace might have a review board for legal purposes, it’s not the only way to distribute your apps. You can also make them downloadable from your site, meaning that you can distribute your screen-breakin’, hard-cussin’, dragon porn Windows Mobile app without The Man steppin’ on your throat.

Now isn’t that nice?

Next

In the next installment, I’ll provide a quick-and-dirty intro to writing your own Windows Mobile apps.